Empty your bladder, find a buttock-friendly perch, and affix a ‘DO NOT DISTURB’ sign to your person before diving into this fascinating 7000-word essay on Japanese rail sims. Open October contributor LBSC doesn’t just discuss relatively well-known-in-the-West offerings such as BVE and Densha de Go, he shines light on local hits such as Ongakukan’s TS series, and lionises a current Early Access title that may well have passed you by.

“Few countries can claim to have their railways as part of the international image, but Japan can proudly claim that honour. Justly or unjustly, the Japanese rail network has a reputation on a par with the Swiss for efficiency and reliability. Unsurprisingly there is a lot of interest in Japanese railways both at home and abroad, but outside Japan that interest has not converted into an interest in Japanese train sims.

This is a shame, for Japanese train simulators are idiosyncratic in very interesting ways, and depending on what you’re looking far surpass their Western counterparts (in other aspects, of course, it’s the other way around). In the hopes of introducing them to the uninitiated, I have written this article to give a tour of most of the major Japanese train simulators, as well as a couple that I find personally interesting. Of course I couldn’t cover everything, but I think there aren’t any obvious omissions.

Before we begin, two notes. Firstly, I talk a fair bit in this article about the Japanese train sim community and its reactions. This is only my impression based on what I can glean from Google Translate, and absolutely shouldn’t be taken as an authoritative source. The second is that this is somewhat of a rambling article. I apologise for this, but this article took a long time to write and heavily editing it would probably have put me past Tally-Ho Corner’s Open October deadline.

Let’s start by looking at Japanese content in Western train simulators.

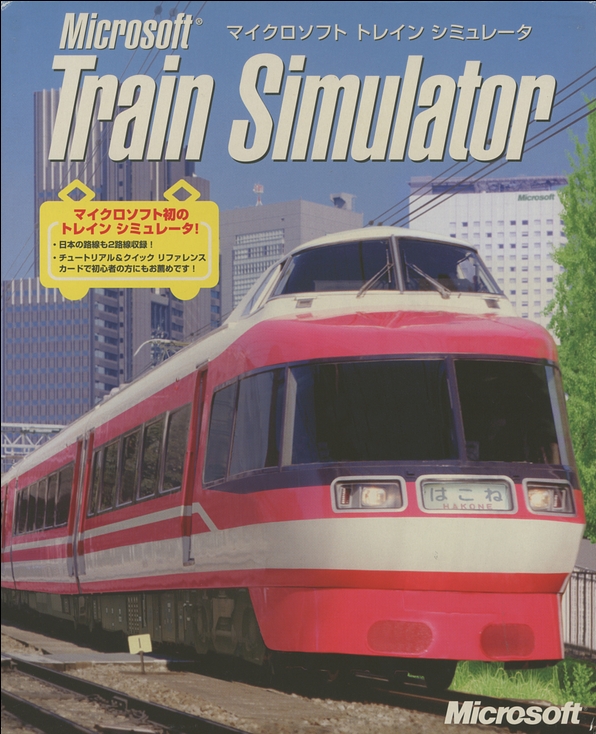

– Microsoft Train Simulator –

To many Western train sim enthusiasts, the idea of Japanese routes in train simulators will always be indelibly associated with Microsoft Train Simulator (MSTS). Out of the six routes included in the 2001 Kuju-developed, Microsoft-published title, two of them were Japanese: the Odakyu Electric Railway between Tokyo and Hakone and JR Kyushu’s Hisatsu Line between Yatsushiro and Yoshimatsu.

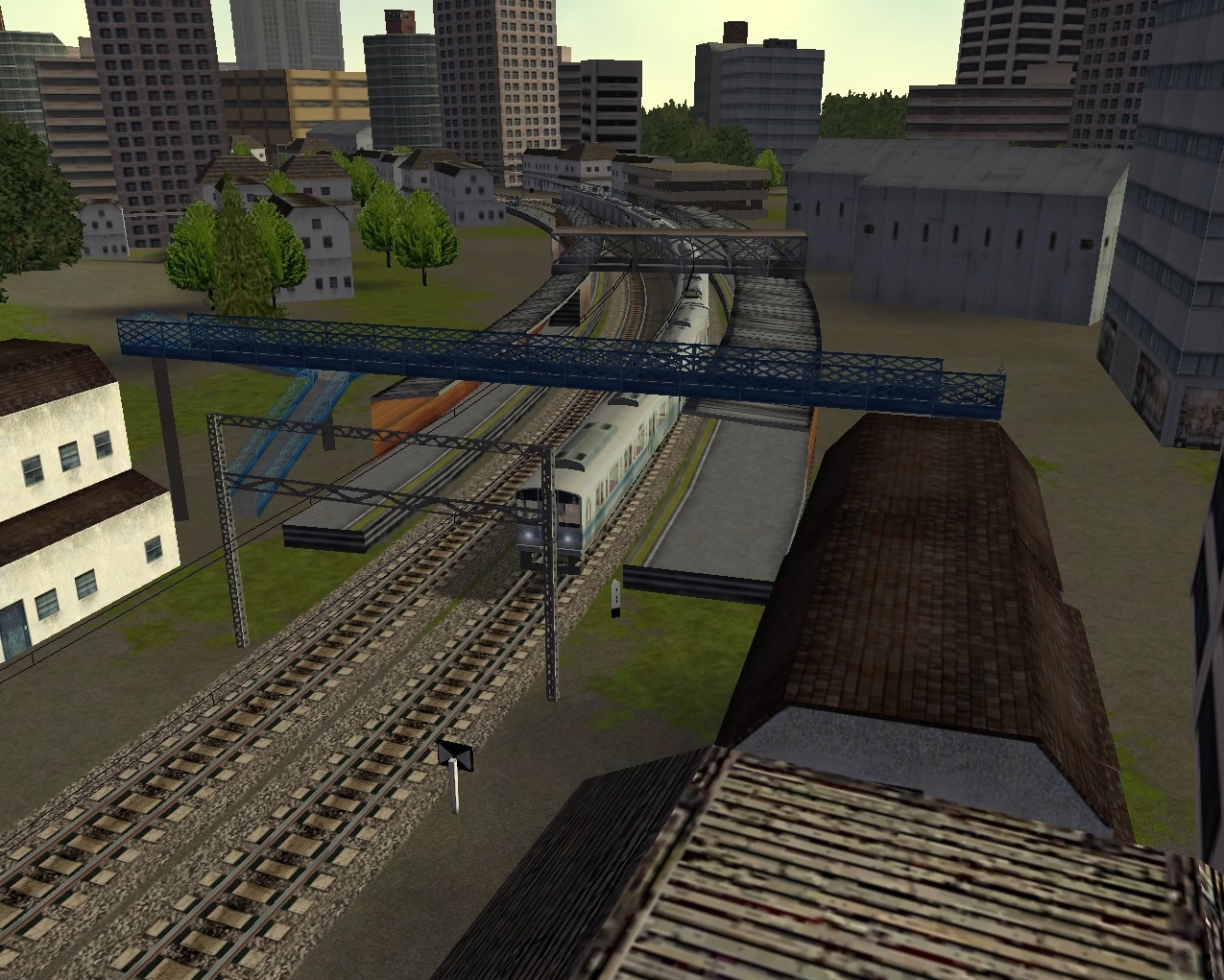

Unfortunately, neither are MSTS’s high point (that would, I believe fairly uncontroversially, be Marias Pass). MSTS in general has hardly aged well – the graphics are poor, the controls clunky, the sounds grating, and the routes under-utilised (neither Japanese route has any scenarios that traverse their full length). But some routes got more attention than others in what was by all indications a rushed development cycle, and the Japanese routes were clearly lower priority than others.

Perhaps the most serious issue with the routes is how MSTS appears to have been built with the simulation of American railroads in mind first and foremost, with other countries’ rail networks being forced to fit an American mould. This caused a large number of issues, from minor ones like giving signal aspects the names of comparable American aspects, to serious errors like the American-style air brake simulation, completely ignoring how passenger train brakes are invariably controlled using notched brakes in Japan.

Most seriously of all, all the Japanese trains are a third too big – they have been scaled up to fit on standard gauge (4ft 8 1/2in) track instead of the 3ft 6in track they run on in reality. As the routes were not scaled up to match, this leads to obvious errors like trains severely overhanging platforms.

That said, MSTS is not without its charms. These mostly come from the Hisatsu Line – MSTS is ill-suited to creating the atmosphere of a busy urban commuter line such as Tokyo-Hakone, with the haphazardly strewn buildings and the eerie 28 Days Later-style atmosphere created by MSTS’ lack of any humans, even in such an environment as downtown Tokyo (why humans were omitted from the game remains a mystery to this day, I believe).

The Hisatsu Line, on the other hand, manages to come off as charmingly low-poly. Being set in rural mountains, the lack of people is less unsettling, and it avoids the problem seen with Tokyo-Hakone of the edges of the sceneried area being clearly visible. That the Kiha 31 railcars drivable on the route are overscale is far less noticeable due to their short length, and the route features unique elements such as switchbacks. It is still a default MSTS route, with all that implies, but for those who have nostalgia for the game playing it won’t shatter their rose-tinted glasses.

MSTS had little impact in Japan, as far as I can tell. While fully translated it attracted little attention and seems to have failed to draw users away from native train simulators. It did however manage to attract the attention of two Japanese payware developers; a company named Twilight Express produced five payware addons featuring a variety of Japanese routes; these apparently were somewhat above the quality of the default routes but not by much. Another company named Aerosim, predominantly active in the flight sim market, produced two more payware routes. Some (but I believe not all) of these addons were released in Europe by the German company Simaviator. Information on them (in Japanese) can be found here: http://sylph.lib.net/trainsim/msts_addon.htm

A few freeware items of Japanese stock were produced by the Western community, but only a few and with the primary focus of the remaining MSTS/OpenRails community being on simulating American railroads this seems unlikely to change in the future. Let us move on.

– Train Simulator Classic –

The history of what was originally released as Railworks and is now known as Train Simulator Classic is thankfully not especially relevant here. It suffices to say that the game in question changed its name every year, usually changing the year at the end, for over a decade before finally settling into what appears to be some sort of stability last year. For the subject of Japanese routes, this is only relevant as an explanation for why historical articles on these routes refer to the game as Train Simulator 20XX (replace last two digits as appropriate).

Railworks initially released with routes from the UK, the US, and Germany, and despite frequent changes in the routes included with the base game this “holy trinity” of countries represented has never changed, with developer Dovetail Games nearly exclusively producing routes set in these three countries, with the exception of brief forays into France and Austria. Therefore all Japanese content has come from third-party developers, though all Japanese payware has been published by Dovetail on Steam.

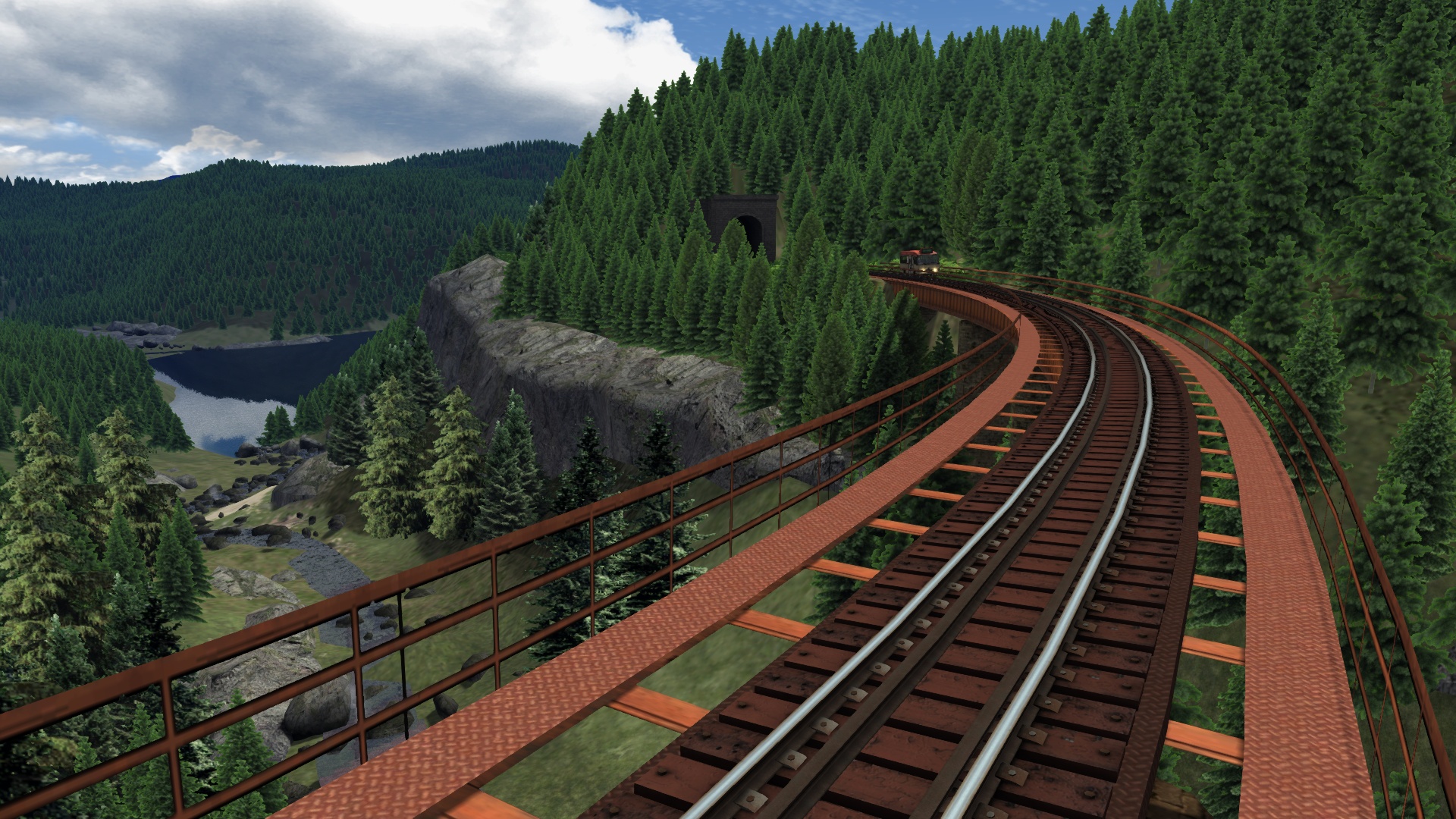

So far all Japanese TSC payware has been produced by a two-man Chinese outfit named Union Workshop. They first dipped their toes into the water of Japanese payware (after previously releasing a free Shinkansen route) with The Story of Forest Rail in 2015. This semi-fictional route, inspired by a real line in Hokkaido, is hardly the pinnacle of their work, but seemingly did well enough to prove that a demand for Japanese content existed, and thus all their future routes, starting in 2016 with the Wakayama & Sakurai Lines route, would be directly based on real life routes and strive for accuracy.

So far Union Workshop has released six Japanese routes covering a wide variety of subjects, from rural branch lines to the famous Shinkansen. While the quality and features of these routes varies, Union Workshop are to be commended for the amount of content they pack into each route. Each route is packed with scenarios usually covering most types of regular service on the line, and the lines themselves are of a good length – the Tohoku Shinkansen route even manages to span 175km.

Where Union Workshop falls down is on precise accuracy. Not living in Japan and not having licensing agreements with any Japanese railways, they are forced to recreate things as best they can from publicly available information. In most cases this is not too large a barrier, but they have made mistakes in the past (some of which they have corrected, to be fair) and in the absence of any licensing agreements they have been forced to replace all JR branding with that of the fictitious “Union Railway”. Their work also, of course, suffers from the issues all TSC content shares, especially that of poor performance on anything other than the beefiest CPUs.

But still I would recommend Union Workshop, at least if you want to play Japanese routes through TSC. Unfortunately they are essentially carrying the entire weight of Japanese content in TSC on their backs. Western-produced Japanese TSC content is very sparse indeed – the only creator I can find is a French producer of freeware called Pierre G, who has produced some basic Japanese rolling stock and scenery: https://ajrailsim.pierreg.org/

Japanese interest in TSC has been minor, especially since I believe it never received an official translation. Nevertheless a small community does exist, and has produced things like a basic fan translation. Perhaps unsurprisingly, this community seems to be primarily comprised of people interested in non-Japanese railways, with Union Workshop’s content seen as an interesting curiosity – Japanese railways seen from outside – and thus little Japanese-produced Japanese content for TSC exists. What little there is has primarily been produced by a user named Rainbow Stream, who has produced two basic trains and a variety of patches for Union Workshop’s routes to correct various details: http://sunstep64.okitsune.com/ts/downloads.html

That ends my discussion of Western train sims with Japanese content. I know Trainz has Japanese content, but I’ve never been a Trainz person. Union Workshop are apparently working on a Japanese route for Train Sim World, but that seems unlikely to come out any time soon. So let’s move on to simulations of Japanese railways produced by the Japanese themselves.

– Defining Characteristics of Japanese Train Sims –

Japanese train simulators are quite different from Western train simulators. They have different founding texts, for starters. While Western train simulation, for better or worse, has always been in the shadow of MSTS, Japanese train simulation can trace its origin to mid-90s titles like Ongakukan’s Train Simulator and Taito’s Densha de Go. These established several core differences that set Japanese train sims apart.

The first is game-like elements. Even titles that place an emphasis on realism like Ongakukan’s Train Simulator or the recent Train Crew often include scoring systems. Several Western train sims also include scoring systems, of course, but Western scoring systems are far simpler than Japanese ones and often receive criticism from more “serious” players.

Another core difference is on what players are scored on. Keeping to the timetable is heavily encouraged, of course. But even more important is stopping in the right place. Most titles demand that the player stop within three metres of the stop marker, and quite often impose even stricter limits.

Japanese train simulators are also invariably first-person only. While obviously this has to be the case with the FMV titles (more on these later), it is also the case with the 3D-rendered titles as well. Sometimes third-person camera views are available, however unlike the freely controllable third-person cameras found in Western train sims these are nearly always locked to pre-set locations and angles.

Another omission from many (but not all) Japanese train sims is the ability to drive routes in both directions. While to Western train sims this is a feature so basic not including it would be more work than including it, many Japanese train sims only feature services that traverse the route in one direction.

Music is an interesting feature that is again absent from Western train sims. While generally not present in gameplay itself, payware Japanese train sims invariably feature music in menus, and indeed usually have quite extensive soundtracks.

Finally, while Western train simmers have been stuck for years trying to fit the ageing and US-focused Raildriver to fit their rail controller-shaped holes, in Japan a plethora of train sim controllers from different companies have been released, usually in conjunction with the releases of train sims on consoles.

With that overview out of the way, let’s begin the tour proper.

– Ongakukan –

Ongakukan’s Train Simulator series came from an unexpected place. Founder Minoru Mukaiya came to public prominence as the keyboardist for jazz fusion band Casiopea. In 1985 he founded Ongakukan (literal translation: “Music Hall”), which was initially a rental company for recording equipment. In 1993 they entered the software industry with the Casiopea-themed program “Touch the Music by Casiopea”. In 1995, however, apparently based on Mukaiya’s long-standing railway enthusiasm, they began producing train simulators, starting with Train Simulator JR East Chūō Line 201 Series.

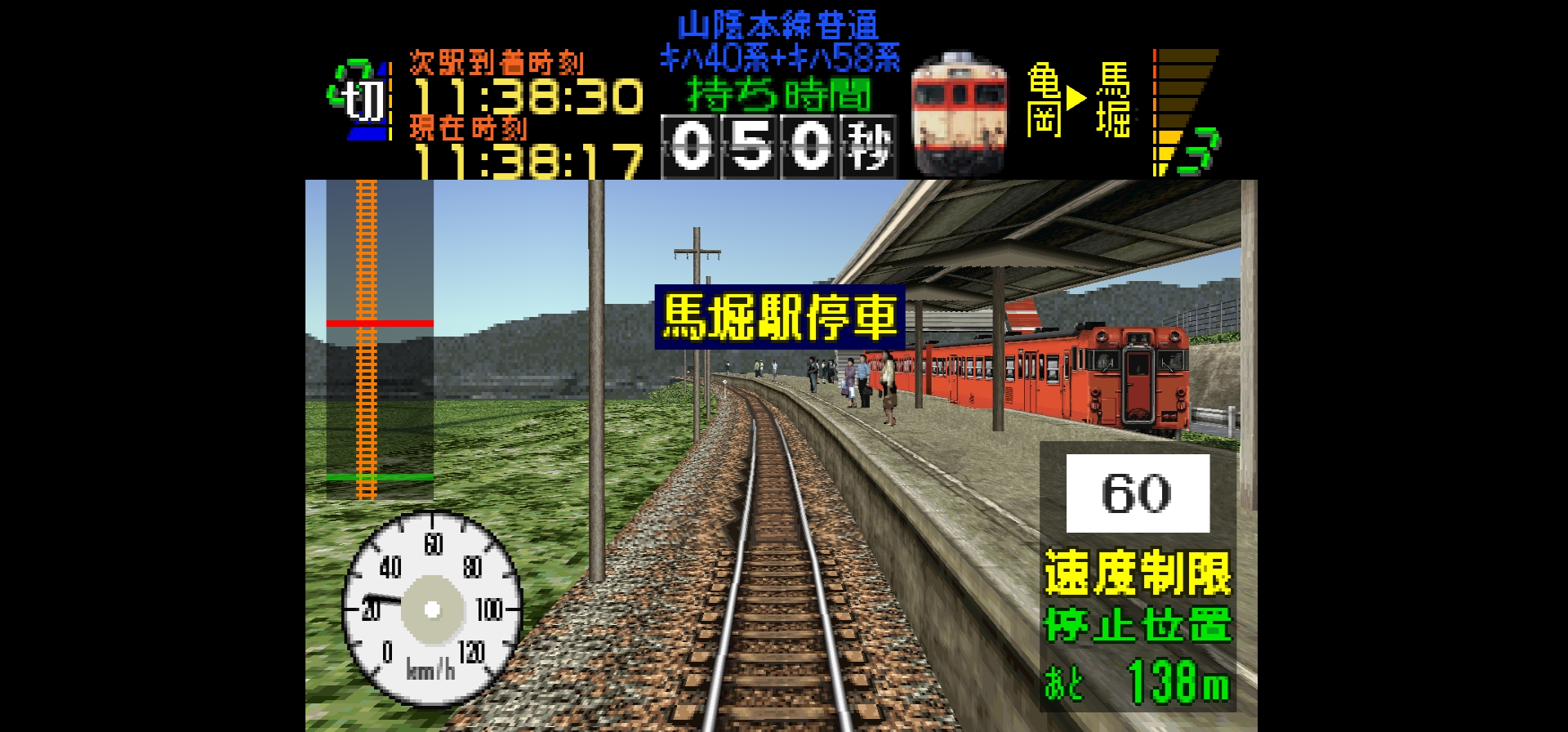

As can be seen from the video, the distinctive element of Ongakukan’s titles is their use of live-action footage that is simply sped up or slowed down depending on the player’s speed. I shall leave my discussion of this to the end of this section.

Onguakukan were extremely prolific, releasing 21 titles on the PC between 1995 and 2001, not just covering Japan but also taking excursions to France and Germany as well. Unfortunately I have not as of yet had the opportunity to play any of these titles, so I cannot pass judgement on them.

The first Ongakukan titles I can comment on are those released for the PS2. For some reason, after 2001 Ongakukan abandoned the PC market and started solely producing titles for PlayStation consoles. In total they released six titles on the PS2, two on the PSP (both ports of PS2 titles), and two on the PS3 before going on an over decade-long hiatus.

The PS2 titles increased in scale as they progressed. Initially starting out with a limited amount of content, usually featuring just one train on one line. However the amount of content included in each game rose until with their penultimate PS2 title they reached what I think is the pinnacle of the entire series: Train Simulator: Keisei, Toei Asakusa, Keikyu Lines.

This title covers the standard gauge commuter network linking Tokyo’s two airports with the city centre and each other. The section depicted in the game covers 102.1 km of track, operated by three different companies with a bewildering variety of services and rolling stock. Not only is as much gameplay wrung out of this route as the limitations of the live-action footage allow, with as many different services represented as possible, but the title also introduces new methods of gamifying the simulation, which I think are a success.

At the start of the game, the player is asked to pick one of the three railway companies, and is restricted to only driving services of that company. However, once enough services are completed, another company is unlocked, and so on until all three lines are available. But this is not the only game element. The player is scored during their services (gaining points for e.g. arriving on time and at the correct stop position, and losing points for e.g. speeding or arriving late), and the points gained in a service can afterwards be spent to unlock new trains. Because of the high degree of through-running on the network depicted, a single service can be operated by over ten different trains, all with their own unique characteristics, so the replay value is fairly high, especially since the point system incentivises going for a high score.

For some reason Ongakukan decided to rebrand the series as “Railfan” for its PS3 releases. This actually gained a small amount of attention from the Western games media for three reasons. First, it launched just a month after the PS3 did. Second, its use of FMVs meant that Sony was eager to promote it at events like the Tokyo Game Show, as it benefited from the PS3’s support of blu-rays. Third, it featured the Chicago Transit Authority Brown Line.

Now Ongakukan had made routes set outside Japan before – in the 1990s they produced simulators set in Germany and France. But something about a Japanese company producing a simulation of an American line – a country as far removed from Japan in its rail culture as possible – produces something fascinating. No Western studio would list the distance to the next station in ten-thousandths of a mile. Nor is it likely they would make sure the announcements were authentic, or include a tour guide of landmarks along the line.

Judging it as a whole, I would say Railfan is the second-best of the Ongakukan titles. It includes two Japanese lines as well as the CTA Brown Line, has a variety of modes, and greatly benefits from the increased resolution the PS3 affords it. Sadly it would effectively be Ongakukan’s swansong. Ongakukan would develop one more title for the PS3 – this time covering Taiwan’s high-speed rail – but this would be their last video game for fifteen years.

During the development of the Train Simulator series, Mukaiya had created many connections with people in the Japanese railway industry. As a result, he started getting commissioned to write departure melodies for various railways. But this was only the beginning. In 2006 Ongakukan was commissioned by the Tokyu Railway to produce a driving simulator to train its drivers, and soon after Ongakukan was producing simulators for museums as well. After the release of Railfan Taiwan High Speed Rail in 2007, Ongakukan left the home simulator market entirely, focusing entirely on crew training and museum simulators.

It was not until 2022 that Ongakukan would finally return to making home simulators, with JR EAST Train Simulator. Not only was this the first home simulator from Ongakukan in fifteen years, but it was the first of their simulators to be released in the West, and came with a full English translation. However it did not receive a great reception ‘abroad’. In large part this was due to the paucity of content included in the base game – your $29.99 only bought you short 5km preview sections of three routes, with the full versions of each route available for another thirty bucks each. An update included the full 81km Keihin-Tohoku line as part of the base game for free, but other issues remain. Common criticisms in Steam reviews include the lack of content available in each route (usually just two or three different services), severe glitches running at resolutions higher than 1080p, barebones UI and missing features (there is no scoring, for instance), and several more besides. The reception in Japan seems to have been somewhat more positive; no doubt this in large part due to the issues mentioned not being new to Ongakukan’s games and therefore being something Japanese players are used to; the game is also cheaper in Japan.

And now finally to talk about the core unique element of Ongakukan’s simulators; their use of live-action footage. This both works better and worse than one might at first think. To start, it is important to understand how the live-action footage was recorded for them. They were not recorded from regular service trains; instead they were recorded from special non-stop trains. This allows the games to feature services with a variety of stopping patterns. The immediate objection one may have to this – that passengers on the platforms would freeze when the train stops – is not as great a problem as it might be imagined to be, as normally the stopping point is far enough down the platform that passengers are not visible; however, in some cases it is a problem. The more serious issue when stopping at stations is that at the framerate the videos were recorded at, speeds below 5km/h make the individual frames far too clear – it breaks the illusion when the distance counter is smoothly ticking down while the video is lurching frame by frame.

Outside of stations, the illusion generally manages to be kept up as long as you drive as you’re supposed to – indeed it’s surprising just how much your brain accepts the video as being just as “real” as a regular 3D sim, as well as still feeling like something you’re controlling. Unfortunately red signals do spoil the illusion as they require you to stop in places where things may be moving in full view of the camera, and often you won’t be travelling at a sufficiently close speed to the recording train’s for things to quite match up. There is also, of course, the issue that you will see the exact same things at the exact same places every time you play a route, as well as sometimes obvious splices between footage recorded at different times.

These are all major issues with the concept of FMV train sims. But there is one thing they have over traditional train sims, and it’s not a small thing: they are Real. Even the most lovingly detailed route in a 3D train sim will inevitably have errors and missed details. But with an FMV train sim the visuals are accurate down to the precise clothing of the passengers; how could they be otherwise? And then there are the small details that the developer of a 3D route would never think to include, from the appearance of aircon units on buildings to birds flying in front of the train. Finally, there are the large details that a commercial developer of 3D sims could not include for reasons of legality; a 3D Keiyo Line would undoubtedly be obliged to replace Tokyo Disneyland with a generic theme park at Maihama station, but the live-action JR East Simulator can have it in all its glory.

On the subject of gameplay rather than graphics, in many respects I can’t comment as I don’t know enough about Japanese trains. But in general from what I can glean from the Japanese web they seem accurate enough, and things like safety systems are accurately represented to the best of my knowledge. Certainly of the commercial Japanese train sims Ongakukan’s titles are the most focused on recreating reality. We’ll next take a look at a series that takes precisely the opposite approach.

– Densha de Go –

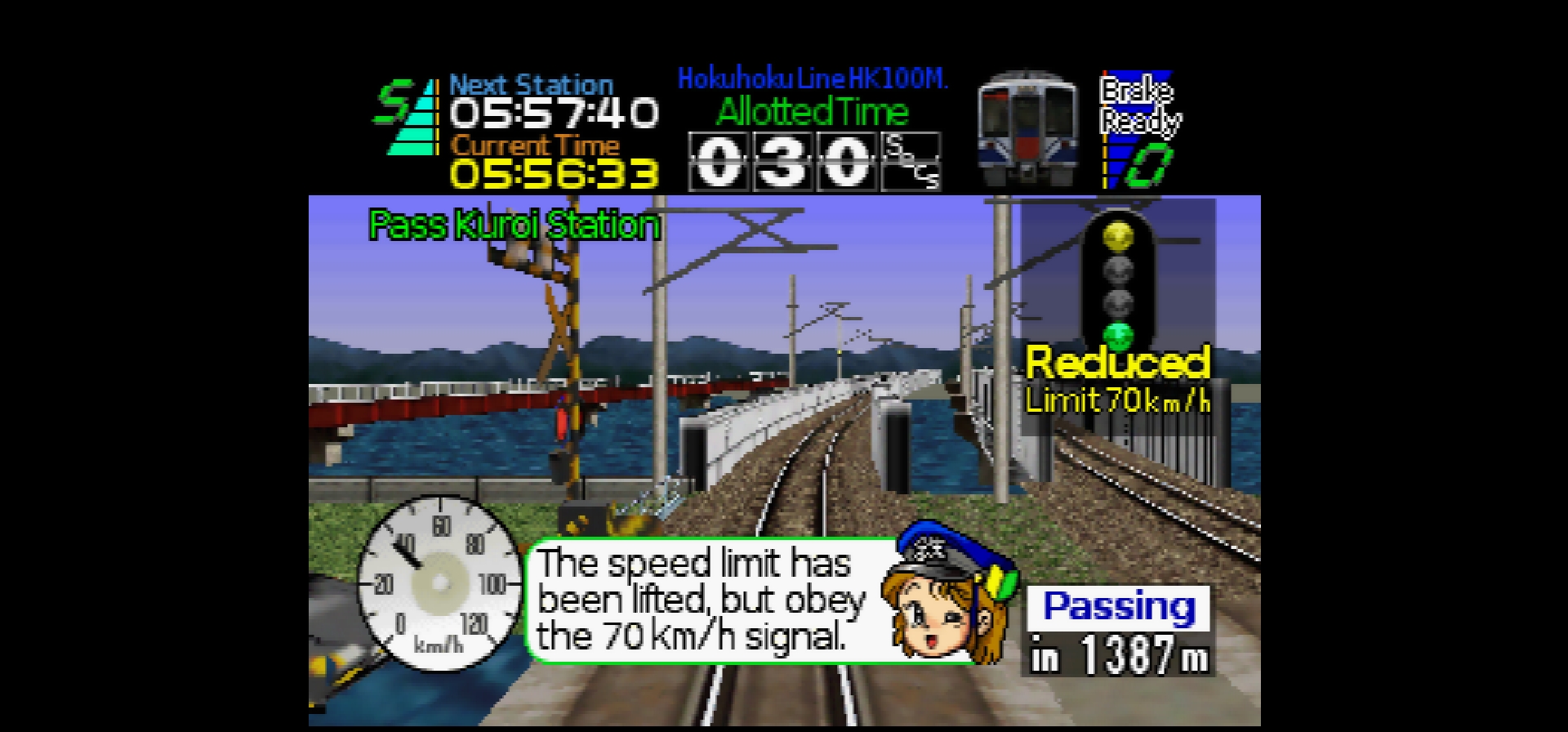

Whether Densha de Go (literal translation: “Go by Train”) can even be called a train simulator is not entirely clear. But there isn’t really anything else to call it. Other genres like racing have terms like “simcade”, but the lack of any other games like Densha de Go leave it floating in limbo as one of a kind. It’s worth checking out for this alone, but even for the simmer who prefers their titles realistic some Densha de Go titles have things to offer.

The first Densha de Go, released to arcades in 1996, was produced quickly and on the cheap – unsurprisingly as Taito was taking a risk and were uncertain on whether or not it would be a success. It was developed in just four months and reused hardware from a sticker printer. But Taito’s gamble that a train-driving game would have broad appeal paid off.

Undoubtedly a large part of its success was due to the cabinet itself, something that supposedly took up 80% of the development cost. While a simple cabinet with train-like controls would have got the job done, Taito went all-out with the design. Inspired by the cab of the 205 series EMU, the Densha de Go cabinet is a stunning reminder of the advantages arcade cabinets have even with a singleplayer game like Densha de Go that could (and was) be easily ported to home media without losing anything gameplay-wise; it is packed with details such as brake pressure indicators and door interlock lights, none of which are strictly necessary for gameplay but sell the fantasy wonderfully.

Densha de Go succeeded beyond Taito’s wildest dreams. Arcades were flooded with customers who would normally never step foot in them. News reports were fascinated at the sight of businessmen in an arcade at Tokyo station all huddled around Densha de Go cabinets. Console ports, merchandise, and other spinoffs were hurriedly produced. At the height of the boom Taito was even prototyping extravagant arcade machines like Densha de Go N-Gauge Edition, a combined model railway and arcade machine where players controlled a model train with a camera attached. However, this boom would not last.

The first Densha de Go games were yen-sucking arcade games through and through, punishing the player for such offenses as arriving at a station three seconds early and providing very little warning of upcoming speed limits. And for all its difficulty, once you had worked when and where to apply power and brakes and by how much, it offered no further challenge – you just did the exact same thing over and over to win every time – and there were only four short routes, so this happened quickly. The boom soon faded, and just four years later the last arcade title in the series for seventeen years was released. The series became confined to home consoles and computers like its competitors, and it is these titles I shall give an overview of.

The first Densha de Go titles are a bewildering variety of ports and updated re-releases. Thankfully all the actual content can be found in two games. The first is the Nintendo 64 port of the second arcade game, named Densha de Go 64. Not only does it include all the arcade’s content plus additional routes exclusive to the home version, but it is one of two titles in the series to have an English fan translation. The second is Densha de Go Professional, released for the PS1 and PC. This is where the series started to shift towards a focus on home consoles and computers. Compiling all the routes included in the PlayStation ports of the first two games (including all the arcade routes and a wealth of additional routes, only lacking some of the additional routes included in some of the ports of the second game, which can be found in 64), it significantly reduces the difficulty by including such features as a map warning of upcoming speed limits and signal aspects. While still an arcade game at its core, the sharp edges have been blunted significantly.

From here on things thankfully get much simpler, as the console and PC games started featuring entirely original content. Densha de Go Nagoya Railroad is essentially just Professional with a different set of lines solely covering routes operated by the Meitetsu company – it’s an interesting historical artefact nowadays, as several of the routes depicted in it have been closed.

The final title released for the PS1 was Kisha de Go, the series’ only attempt at simulating steam locomotives. Unfortunately it was not a success. The steam simulation was both completely inaccurate and far too complicated for arcade-style gameplay, and it also reverted all the quality-of-life features introduced in Professional.

I don’t have much to say on Densha de Go 3. Since it was the series’ next arcade title, it followed Kisha de Go in it’s removal of the home versions’ quality-of-life features both in the arcade version and its home media ports. It did see a significant leap in the series’ visuals though, being the first title ported to the PS2.

I have significantly more to say about the next arcade title. For starters, this was the last arcade game in the series for seventeen years. It also saw the Densha de Go name being dropped, it instead being named Ganbare Untenshi! (literal translation: “Good Luck Driver!”). Also unlike previous arcade titles, which had all used the same cabinet with different internals, Ganbare Untenshi made significant changes to the controls to fit with its refocus on driving trams rather than trains. The new features like opening doors and playing announcements were generally well-received, and despite being an arcade title it toned the difficulty down significantly compared to previous arcade titles.

However I won’t be discussing Ganbare Untenshi’s home port just yet, as it was actually released two years after its arcade release. In between, Taito released the next home-only title, Densha de Go Sanyo Shinkansen. Sanyo Shinkansen saw further moves towards realism – you could turn on more realistic versions of the safety systems, and the services you drive are based on real-life timetables – but unfortunately it is probably one of the dullest titles in the series. High-speed rail tends to have a soporific effect in simulations, and Sanyo Shinkansen does not avoid this despite compressing the Sanyo Shinkansen route to a quarter of its real length. It was the first game to allow you to drive the routes in both directions, something that would remain for the rest of the original series.

Next in the series was the port of Ganbare Untenshi, though calling it a “port” is severely underselling it. Renamed Densha de Go Ryojo-hen (literal translation: “Tourism Edition”), presumably to make it obvious it was part of the Densha de Go series, the home version, released on PS2 and PC, was packed with massive amounts of extra routes and content not present in the arcade original. It also nearly completed the filing down of the sharp edges present in the original arcade games – it is a far more forgiving game, with several mechanics being able to be turned off entirely.

Overall I would call Ryojo-hen the best game in the series at its release, and indeed as simulations of Japanese trams remain very rare indeed it is well worth checking out today. However the crown jewel of the series was yet to come.

Skipping over Densha de Go Professional 2, a series instalment with all new content, brings us to…

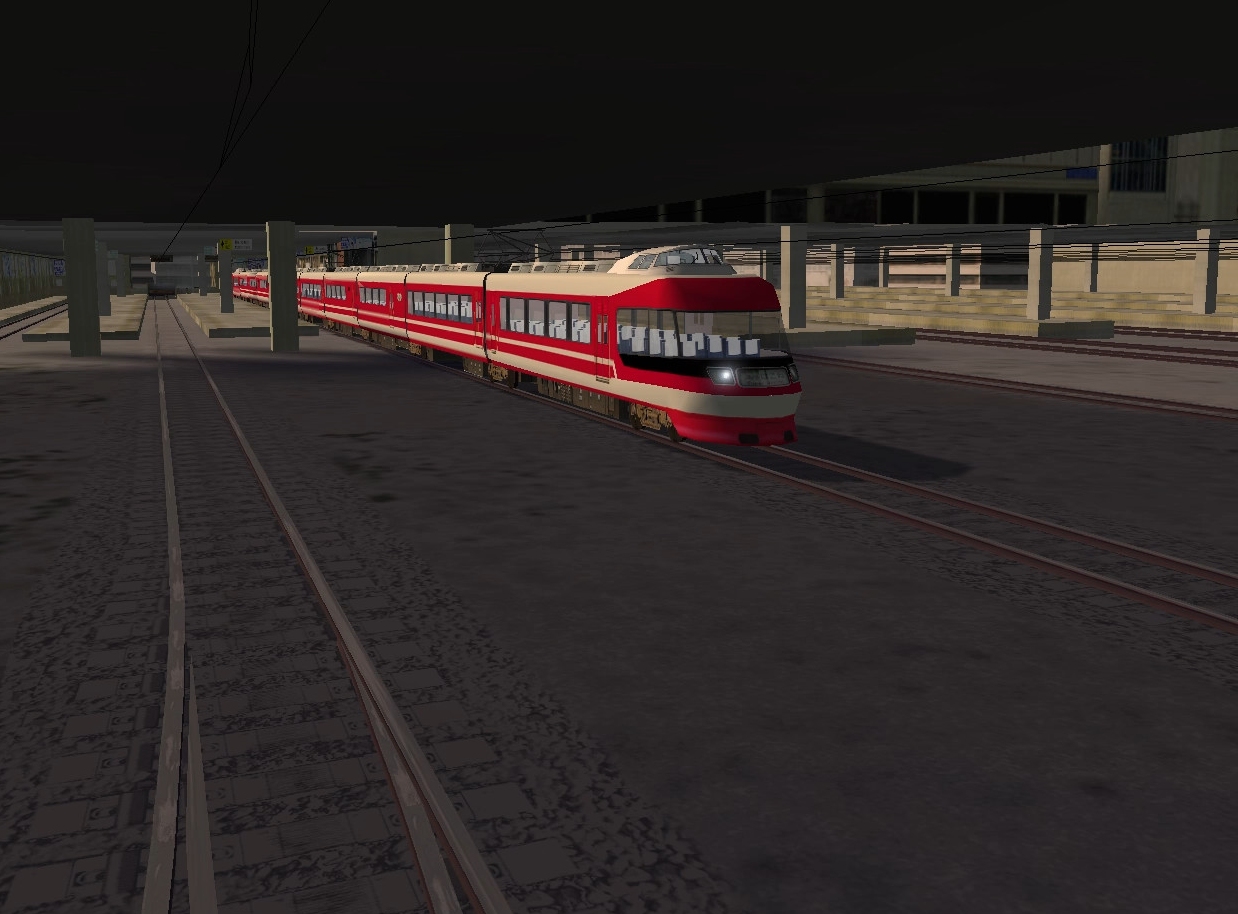

Densha de Go Final, released in 2004, was the last title produced in the original series. Precisely why the line ended here is somewhat unclear – personally I suspect Taito feared market over-saturation, while officially there was talk about them reaching the limits of what contemporary console hardware could accomplish. In any case, the series certainly went out with a bang.

Final places more emphasis on realism than previous titles. While earlier titles had compressed routes, two of Final’s four routes are presented in their full length, and the other two are only slightly shortened. It oozes authenticity from every pore, from the accurate timetables to the massive variety of passing trains to all the announcements one would find in real life being present. It’s still simcade at its heart – it’s still a game where every single train has five power notches and eight brake notches, and where ATS sends you screeching to a halt the second you go a single km/h above the speed limit – but it strikes a balance between realism and fun that previous titles didn’t quite manage.

Outside of its realism, Densha de Go Final is just jam-packed full of content. Its four routes are long and feature ten to twenty services each, covering pretty much all types of services that run on the line in real life. These services themselves are usually so long they’re split into multiple sections. Best of all, it is the other game in the series to receive an English translation, and it is most definitely the most deserving.

After Densha de Go Final, the series went on a long hiatus. A few ports of existing titles were produced for the PSP and Wii, but otherwise the series lay dormant. It was not until 2017, with Taito now owned by Square Enix, that a new arcade title would be produced to commemorate the series’ 20th anniversary. The new title would take full advantages of advancements in technology – it would use the Unreal Engine, be powered by a GTX 1080, and be connected to the internet, with new routes being added over time. It would simply be named Densha de Go, and acted as a reboot of the series.

The cabinet itself is massive and designed to fully immerse the player. It is practically a full scale mock-up of a train cab, and features three screens to create the illusion of actually viewing the scenery through the cab windows. In addition cab controls such as the speedometer are displayed on a touchscreen that changes its display to match the real controls of the train being driven. The production of the physical cabinet itself cannot be faulted.

Unfortunately the game itself, from what I can gather, is a mixed bag. The graphics are certainly of very high quality; unfortunately this makes the schoolboy errors in the depictions of trains, such as the complete absence of pantographs, all the more obvious. Despite being an arcade game, the game is generally forgiving for the inexperienced player if they just want to complete a service (going for a high score is of course a different matter), but sometimes this has led to divergences from reality such as trains having far better acceleration and deceleration than they do in reality. Being a modern Japanese arcade game, it comes with a plethora of online features and high score tables; unsurprisingly, these have attracted a plethora of complaints. It has also attracted a lot of criticism for its high price – the play fee is between 200 and 500 yen depending on the length of the service, which quickly adds up.

There are two points worth mentioning about the 2017 Densha de Go that are worth mentioning. The first is that in an update in 2019, full remasters of the first two arcade games were added to the games. While not perfect, this was generally seen as an acceptable replacement for the old cabinets, which at this point are rare and often malfunctioning. The second is that it is the only game in the series to have an official English localisation, complete with voice acting. The localised cabinet had a location test in a Dave & Busters in Texas, but presumably did not do especially well, as no further cabinets were distributed and the one known example now in the hands of a private collector.

Obviously few people are going to travel to Japan just to play an arcade game. Thankfully some of the content, and all of the mechanics, were ported to the PS4 and Switch in the 2020 title Densha de Go Hashirou Yamanote-sen. In addition to the sections of the Yamanote and Chuo-Sobu lines featured in the arcade version, it also contains the full Yamanote line (the arcade game only has short sections of it). Generally everything said about the arcade game still applies to this version, but it has one major new flaw: it’s just plain boring. The metro-like Yamanote line is just not interesting enough to sustain a full game, especially when it can only be driven in one direction. It’s an interesting novelty, but definitely not worth the full asking price.

Thus ends our journey through Densha de Go. Onto BVE!

– BVE –

BVE is a name that will be familiar to many Western train sim fans, though ironically probably not for its Japanese content. To explain why that is we need to talk about the history of BVE.

The first version of BVE was released in 2000, developed by Takashi “Mackoy” Kojima. It, and all versions of BVE after it, have been freeware, and allow for the production and use of user-created trains and routes – two key differences separating BVE from other Japanese train simulators. BVE stands for “Boso View Express”, a brand name used for rail services from Tokyo to the Boso Peninsula east of it; I am uncertain as to why Mackoy decided to name his simulator after it. The first version was soon replaced by BVE 2, released in 2001, which was in turn replaced by BVE 4 (BVE 3 was a failed experiment) in 2005. As far as I am aware, each version maintained compatibility with content produced for earlier versions.

This is where things get interesting. Western fans had become interested in BVE early on in history. This was primarily not due to an interest in Japanese railways, rather, it was due to the fact that as a simulator of modern passenger operations BVE was far more capable than MSTS, at the time the only real competition in town. Therefore the focus in the Western BVE community was firmly on making and playing their own Western-set routes, with little interest in what the Japanese community was up to.

This ultimately led to a near-complete divergence between the Western and Japanese BVE communities. By the late 2000s BVE 4 was aging and lacked support for modern operating systems. Mackoy started work on a BVE 5 to fix these issues in 2008, but it would take years before it was finished. In the meantime the Western community started work on OpenBVE, an open-source reimplementation of BVE 4 with many added features. By the time BVE 5 was released in 2011 the Western community had moved over pretty much entirely to OpenBVE, and there was little to no interest in BVE 5.

BVE 5 would in turn be succeeded by BVE 6, however unlike previous versions of BVE neither BVE 5 or 6 completely replaced the previous versions. This is due to the fact that each broke compatibility with previous versions: BVE 5 cannot play BVE 4 or BVE 6 addons, and BVE 6 cannot play BVE 4 or BVE 5 addons. Therefore there is still large amounts of Japanese content that can only be played on BVE 4 and/or BVE 5, and in addition while Western creators saw little interest in BVE 5 and 6 some Japanese creators, though not most, took to OpenBVE and made content for it, which of course is not compatible with BVE 5 or 6.

Reviewing BVE is hard because of how dependent it is on user content. Mackoy himself has only produced a few basic routes. Therefore what you get out of BVE is highly dependent on the quality of the route you’re playing, and of course the many routes out there have highly variable quality. But BVE at its best is an excellent simulator. Mackoy started development of BVE because he wanted a more realistic sim that did not omit features of real-life trains for the sake of user-friendliness, and many routes succeed in capturing everything they should. Reading the readme file, or the manual if there is one, is often mandatory. And there are some features that are part of the core game and thus all routes benefit from – BVE trains sway and bounce to a degree very few train sims simulate. And while BVE is not exactly the most graphically impressive sim, I personally find its simple style charming.

A full overview of BVE is well beyond the scope of this article. Instead I will link to this article, which provides an excellent guide on how to get started with BVE and an overview of some of its best routes (I particularly recommend the Sobu/Narita Line). Mac/Linux users should additionally read this guide to getting it to work on Wine, it also comes with its own set of route recommendations.

Onto our final game in this little tour.

– Train Crew –

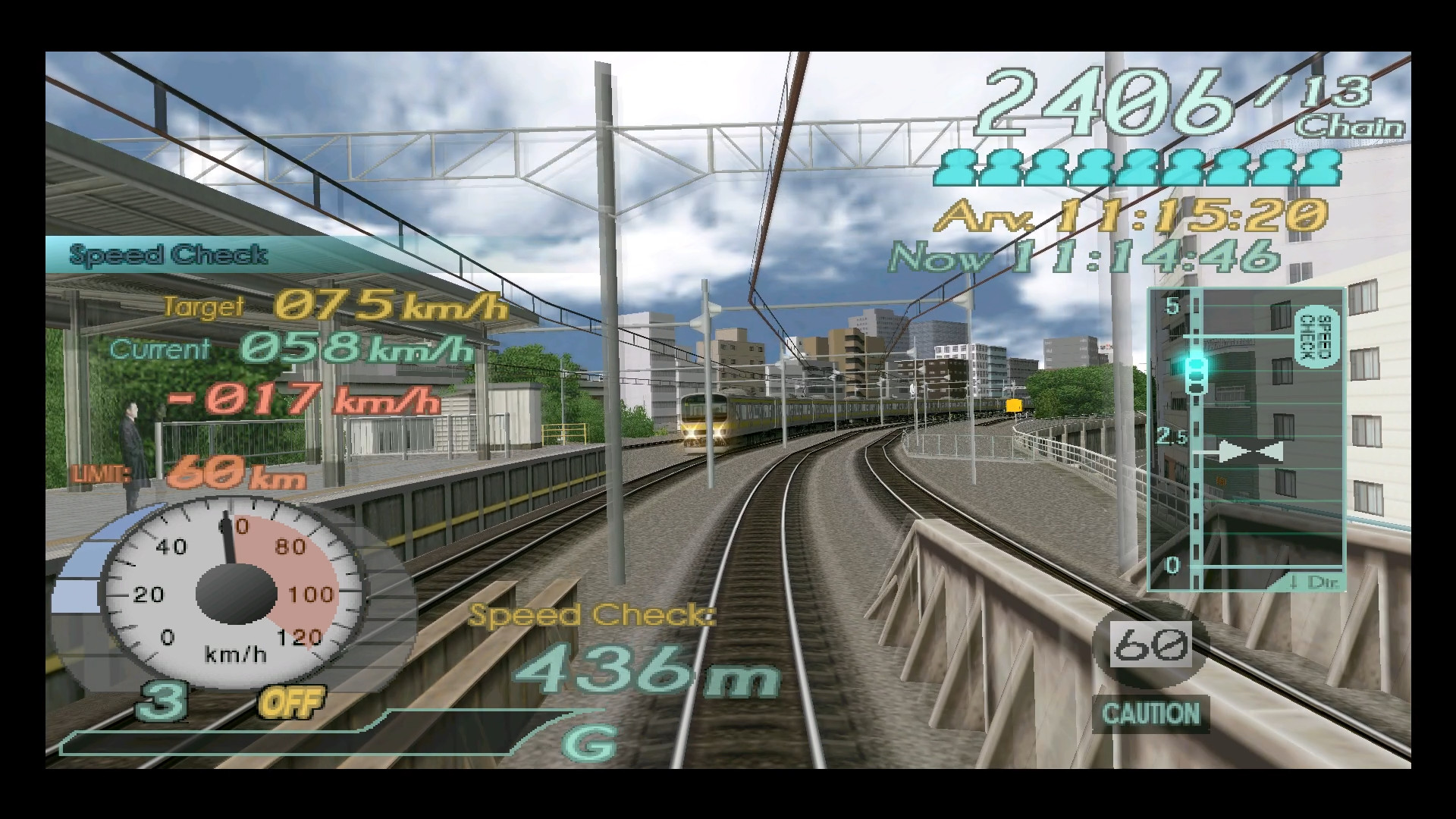

Train Crew does not make the best first impression. It is an early access game made in Unity. Its graphics are poor at best, and not in an especially charming way. Its only route is short and entirely fictional. But look past that, and you’ll find a polished and fun train sim. In many ways it is my favourite Japanese train sim.

While the Tatehama Electric Railway depicted in Train Crew is make-believe, this does not mean that developer acty has ignored realism. Indeed the rules and safety systems of the Tatehama Railway are fully worked out, taking inspiration from various different Japanese railways. The end result feels just as realistic and plausible as a recreation of a real-life route in BVE.

Train Crew succeeds on the gameplay front as well. An in-depth scoring system rewards realistic driving while not punishing new players too heavily, and there are a large number of services to operate, all accessible via an interface that lets you easily see what each service features (empty stock movements, waiting for other trains to pass, etc). But Train Crew’s real crown jewel is Conductor Mode.

Guards tend not to get representation in train sims, even as NPCs. Many sims – TSW being a particularly bad offender – treat all trains as one-man operated. But Train Crew avoids this. Not only is communicating with the conductor via buzzer codes part of driving, but the conductor mode is fully-fledged and features everything you’d want from a simulation of the work of a modern Japanese conductor.

You’ll close doors (remembering to be on the on the lookout for passengers rushing to catch their train), buzz the driver when they’re clear to depart, and play announcements. No other game that I can think of has even bothered simulating the work of the guard, so for Train Crew to do it so well is stunning.

And while the graphics themselves may not on the best side, Train Crew is packed with little details, from the fully 3D cabs, different for each train, to the stations with functional departure boards and platform monitors. It is also translated into English. I highly recommend Train Crew if you’re looking for a Japanese train sim – though perhaps not at full price. It is still somewhat lacking in content, though the developer plans to greatly extend the route.

– Summing up –

So that ends our journey through the world of Japanese train sims. As I said, this covers most of the ones I know about and definitely isn’t complete – for starters there’s Sonic Powered, a company who recently have released a series of FMV sims on PC and Nintendo consoles. I know there are also some PS1/PS2 era titles I can’t remember the names of at the moment. Please comment if you have had any experiences with titles that I haven’t covered.

I hope this article has inspired you to check out Japanese train sims for yourself. Even if you aren’t especially interested in real-life Japanese railways they provide an interesting contrast to Western train sims. The Western community for these titles is very small (and rather Densha de Go-centric in my experience), so I hope that via this article it can grow.”

Thanks for the article, LBSC, it was an interesting read. I’ve dabbled a fair bit in western train sims over the years and my only experience of the Japanese kind was one of the playstation era FMV games which I thought was quite naff really. But that big arcade train cabinet is really quite something. I would’ve loved to have seen something like that in the arcades when I was a kid. Shame arcades are dying out in Japan and are already mostly dead here apart from gambling machines.

I’ve looked at open BVE before but not really paid it much attention, might have another look at it now following your link. Plus that TRAIN CREW does seem quite interesting so I’ll keep an eye on that as well. Cheers!

I would recommend Train Crew. It is getting better with every update. Although it is true that graphics are not the best the gameplay is fun and realistic. It also supports variety of train sim controllers which is good and something I miss in another train sims.

As for JR East Train simulator, the realism is spot on. It is apparent that they developed it based on their simulator software used for IRL training of new drivers. But that comes with some downsides, as is apparent from most of the bugs, when they released it it was quite obvious they hadn’t developed game for home market for a long time. But it looks like they are still working on it so in due time it could be quite good. And to be fair most of the problems come from the fact it is FMV based sim. Also it has fewer bugs than DTGs sims:) Yeah and the price, while it is comparable to TSW, the amount of content you get for the price is not. But it is quite normal for Japanese games to have very high prices even in Japan.

And if you like FMV based sims I recommend checking out Train Operator 377. It has only one route, but the price is ok and it does some clever things to work around the fact it is FMV based. It has even somewhat dynamic weather, sure it does look a bit weird, it is only a filter applied to the real world footage but still.

For BVE5/6 the guide Tim posted is good the get you started, just keep your google translate handy as almost all of the content is Japanese only.

Oh and there is also https://store.steampowered.com/app/2281540/Japanese_Rail_Sim_Operating_the_MEITETSU_Line/ from the guys who developed Japanese Rail Sim: Journey to Kyoto. Seems like it has only one route and it is not in English, at least yet, but it is cheap.

Wonderful! What a fascinating and well-reseached article. Thoroughly enjoyed it.

There’s also the long-running hybrid train/business/city building series A-Train, though it’s not a train simulator as such.

For anyone wanting to get into OpenBVE be aware that a lot of the best routes/trains can be difficult to find and you’ll end up in a sea of dead links. You’ll need to use Wayback Machine to be able to download many of them. There are also a lot of good Korean metro routes that are easier to find and some good London Underground routes that might still be accessible. It is a shame that so much of the user content in OpenBVE is difficult to find as it still remains the best freeware train sim out there.

Thanks LBSC, a nice round up and great to see some of my favourite sims getting some air time.

I haven’t tried Train Crew since its initial release when it was quite bare bones – seems a reinstall is due, though I am put off by the fictional setting.

It was sad indeed that Union Workshop’s Shinkansen route lacked for accuracy in terms of railside buildings and models, the comparison to Densha de Go Sanyo Shinkansen is stark, especially when the latter is booted up in Dolphin emulator with significant graphics improvements.

We’ll have to agree to disagree on the magic of the Yamanote line. 😉

Small note: DDG Final, the PC version at least, has a conductor mode. I have never played (or known of) and English translation of DDG Final however though so unless you are good at reading the names of Japanese stations it is quite challenging. 🙂

Cool article! Very nice to read about sim culture in other parts of the world.

Fascinating and admirably detailed article, thanks LBSC. Stirred up fond memories of me and my JR-obsessed cousin desperately trying to not overshoot the platform (can’t recall which of these sims it was). Well, he did most of the overshooting – I would just sit there and call out “mamonaku” at random intervals.