Reykjavíkian dev Baldvin Albertsson doesn’t simply want to make an entertaining WWI game, he wants to make a thought-provoking and insightful one. In the following Q&A the ex-actor and theatre director describes some of the ways in which upcoming management game Dig In will dig deeper than most Great War diversions.

THC: Were you raised on console games or PC games?

Baldvin: I was born in 1983, and my first gaming experience was on an old 8086 my dad had lying around. We’d play a really old-school flight simulator and a Batman game. I was stunned watching green lines and ASCII codes dart around the pitch-black monitor.

I soon moved on to consoles, eventually getting a Nintendo Game Boy — loved Mario and Tetris. But I got really serious about games when I got a Sega Mega Drive and devoured Sonic the Hedgehog and Mortal Kombat. The latter kind of convinced me that games were here to stay.

When I finally got my own PC in 1997, the first game I bought was Warhammer: Shadow of the Horned Rat. I somehow found myself poking through folders, and before I knew it, I was editing .INI files to get the game where I wanted it. I think that was the moment for me as a game designer. It would just take 20 years for me to figure out I was one.

THC: Are there any similarities between your old life in theatre and your new career in game development?

Baldvin: Running a studio and producing a game means wearing a lot of different hats. Besides managing Vitar Games and doing business development, I also handle game design, level design, sound design, and music — quite similar to when I was directing stage productions.

Having been in the arts, I know exactly how precious a budget is and that you only get one shot at a first impression. We just had a 7-day demo period where Dig In was available to anyone who wanted to play. At the end of it, I felt a lot like I used to after a show: a bittersweet mix of accomplishment and a strange ache of missing it already.

THC: Why was the demo period so short?

Baldvin: A demo at this stage demands a lot of technical support, and as a small team, we chose to focus all our resources on that one-week window. We’re incredibly proud of what we accomplished — especially the high average playtime and the fact that players started modding the demo. But for a small developer, running a demo is expensive. It also forces a feature lockdown weeks in advance, which can slow down development. So we treated it like a special event — and now we’re back to building the full game. The next demo will be announced in the near future.

THC: When and where was Dig In conceived, and how similar is the current version to your original vision?

Baldvin: The idea actually dates back to the ‘90s, but I started seriously working on Dig In in 2015. The idea for the runners came to me as I was playing RimWorld while reading The Price of Glory by Alistair Horne. I had an epiphany one night — I realized I had an idea that combined the best of both worlds.

From there, I got serious validation from industry veterans, and the rest is history. The vision has never changed — no pivots, no shenanigans. It’s exactly what I imagined as a kid.

THC: I imagine you’ve grappled with a few realism-versus-fun dilemmas during the past year. Would you care to give us one or two examples?

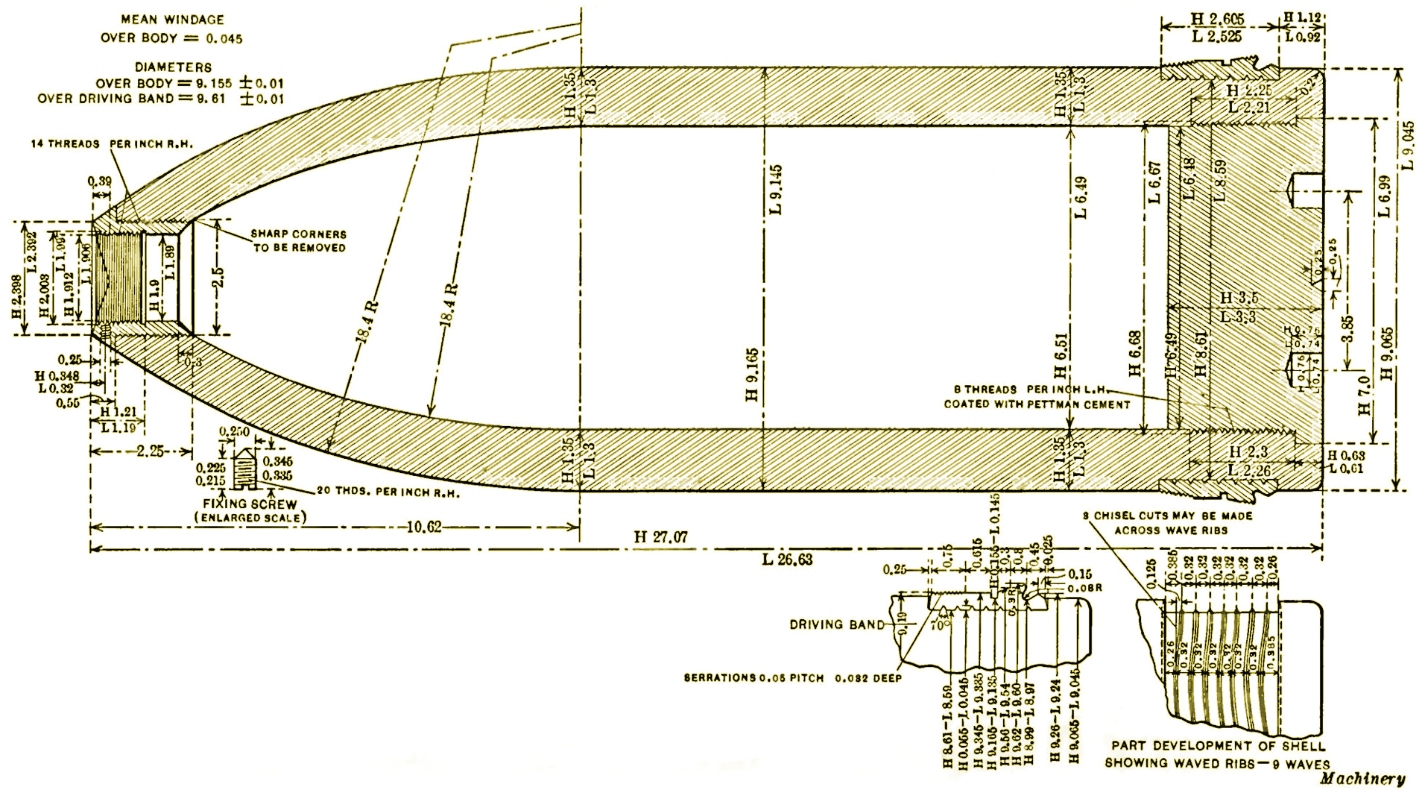

Baldvin: Definitely. One example: artillery. It became clear early on that it would play a big part in Dig In. From a game design perspective, it’s a tricky balance. You want the player to feel the power of unleashing it — but also the horror of receiving it, just like in WW1. It needed to feel immersive and unpredictable.

We solved this through systems design. You want a battery of artillery? Fine. You want them to shoot non-stop? Also fine — just figure out the logistics and keep them supplied. Oh, they’re getting blown up by the enemy? Maybe use them more tactically next time and avoid exposing them.

Another example was the WW1 company hierarchy. If we tried to simulate each nation’s structure with all the ranks and nuance, the game would become too hard to learn. So we simplified: one officer, a set number of sections. We’re still figuring out the exact number of men per section — should it be nation-specific?

That’s why, during the demo, we let players spawn as many men as they wanted — to help us learn.

Also, we have mod support from day one. So if you’re not satisfied, add all those ranks — go for it!

THC: Military tactics games often seem to sanitise war. Will Dig In continue this trend?

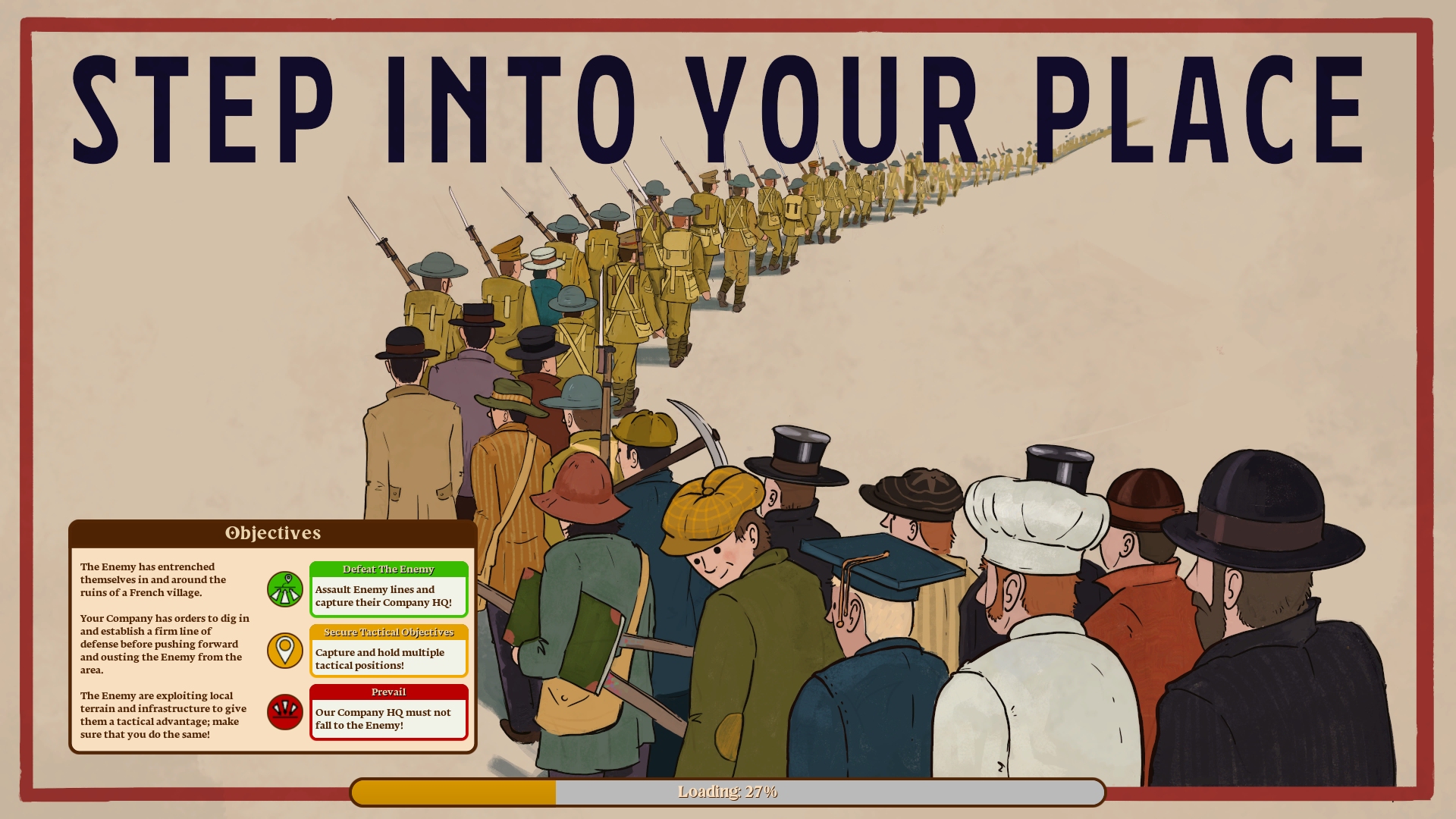

Baldvin: No. I hate war and violence. In the constant cycle of violence we see in the world today, I see no reason why we should contribute to sanitizing it. War is always unjust, cruel, and wrong. That’s why we’ve built Dig In around limited control over individual soldiers. It’s a simulation — one that forces players to think about what it means to fight a war. What are the economics of the butcher’s bill?

That’s also why we implemented the “accepted casualty rate” system. When players deploy a section for assault, they have to ask: how many men are you willing to lose?

As a self-taught history buff, what I find most compelling is learning about ordinary people in extraordinary circumstances. So if we imagine all those “ordinary” people were having the time of their lives and shooting people while getting blown to bits just for the fun of it, we would have a very hollow experience for our players.

THC: Apart from changing uniform graphics, what impact will a player’s nation choice have on play?

Baldvin: We’re thinking nation-specific research trees. So, for example, Germans might get the flamethrower first and faster access to heavily fortified trench upgrades — like those made of concrete.

The French tree would be different — they were fighting a defensive war on their own soil. So we give them more emphasis on assault tactics and élan. The British might research their “mad minute,” and so on. It’s still evolving, but the goal is to reflect real-world doctrine in interesting ways.

THC: Are platoon commanders always competent and conscientious, or will we sometimes be lumbered with hopeless subordinates?

Baldvin: Dig In is all about playing the hand you’re dealt. Your officers might be inspiring leaders of men — or absolute desk generals full of incompetence and existential dread. Like in RimWorld, that randomness creates emergent gameplay. You deal with what you’ve got.

THC: Should we read anything into the fact that Dig In doesn’t have a Steam page yet?

Baldvin: Absolutely. In 2025, around 300 games release every week. That number is only going up in 2026. Finding your audience is harder than ever.

So we asked ourselves: Steam is like Glastonbury — you can play the big stage, but why perform on the biggest stage in the world if only 10 people come? Why not play a smaller tent for 100 who actually want to listen?

That’s why we launched the demo on Itch.io. And honestly, devs today lean way too hard on wishlists. Don’t get me wrong — they’re great. But in a saturated market, wishlists and wishful thinking often go hand in hand. They don’t add up.

But I’ve always loved Steam — the community there is often outstanding. Very dedicated and passionate. I look forward to opening our Steam page this autumn.

Our focus is to build our community first. Without that, we’ll never reach that 1B PC player base.

THC: If you had to make a game inspired by an event or period in Icelandic history, what would you choose and why?

Baldvin: I’d probably go with Skaftáreldar (1783) — the most catastrophic volcanic eruption in Icelandic history. We lost over two-thirds of our farms, and hundreds of people died. We almost got wiped out — but we survived through grit and cleverness.

It would be a survival-style colony sim, for sure.

THC: Game makers seldom seem to have much time or appetite for recreational gaming. Assuming you’re different, which titles do you routinely reach for?

Baldvin: I play every popular game I would never have touched before starting my own studio. I do it to learn — to answer the most important question any dev should ask: Why are people playing this? Animal Crossing — why? Zelda — why? Roblox — why?

THC: Name a game — released or in-development — that you feel deserves more attention.

Baldvin: Over the Top by Flying Squirrel Entertainment. It’s innovative and gorgeous.

Also the Mad Max game from 2015 — massively underrated.

THC: Thank you for your time.

I absolutely love the work you do Tim. Not only do I only hear about games like this because of you, but then you also get devs in for interviews that are always well worth more than the time it takes to read them.

Thank you!

Morale +1. Thanks!

I do find it interesting that he says he doesn’t want to add to the sanitizing of war, but seems to have (at this point) gone with a quite bloodless and cheery art style. Movies like Saving Private Ryan and Stalingrad were heralded for representing the brutal (gory) and depressing (dark, ugly, miserable, immoral) truths of war. I’m curious to see what the final vision for Dig In will be.