Having spent the last two Fridays mercilessly lambasting the EU’s attempts to boost the game development sector, I feel it’s only fair to let some beneficiaries of Creative Europe grants tell their side of the story today. Below the break, devs from Croatia, Lithuania, and Poland, explain why they think the system, while not perfect, is a force for good.

First off, Aleksandar Gavrilovic of Croatian studio Gamechuck proffers his POV.

THC: Overall, do you think CE’s grant scheme is a good thing?

Aleksandar: Many studios have survived because this grant scheme exists, and continue to make video games, which is important in an industry where the turnover rate for employees is unreasonably high as most people who do leave the industry do it forever due to greener pastures in almost any other industry (less overtime, less stress, better pay, etc.). Getting a publisher is harder than ever, especially after 2023, and publishers now seek almost finished games, which precludes any indies from even participating, without securing some funds elsewhere (mostly through grants like this).

Having said that, of course there is always room for improvement. I believe the point structure is better than in the previous period when it openly gave points to games for children (tacitly approving of the ‘games are for kids’ conservative mantra). However, it has been replaced with points for environmental friendliness, which is far from a burning issue for an industry which largely operates on a work-from-home basis and is completely digital in nature.

On the other hand, important issues in the industry like crunch (and recently, mass layoffs) have never been addressed in the point structure. This grant system is still much better than no grant scheme for video games, which was the situation before this grant arrived ten years ago, and which is sadly still the situation in many EU member states (luckily, Croatia introduced a video game public grant a few years ago, but it’s awarded a total of a bit over 500k€ since 2021, so not a huge amount but a good start).

THC: How much difference did the money that you received make?

Aleksandar: We received the grant twice – first in 2019 for the game Trip the Ark Fantastic, which hadn’t found a publisher, so we decided to release it in chunks, with the first part coming out last year – Paws of Coal (2023), and was (apart from some bugs we needed to fix) well received and was nominated for Best Narrative on GIC Poznan, as well as the first Croatian game ever showcased on AdventureX in London. Without the grant we couldn’t start the studio and gain valuable input.

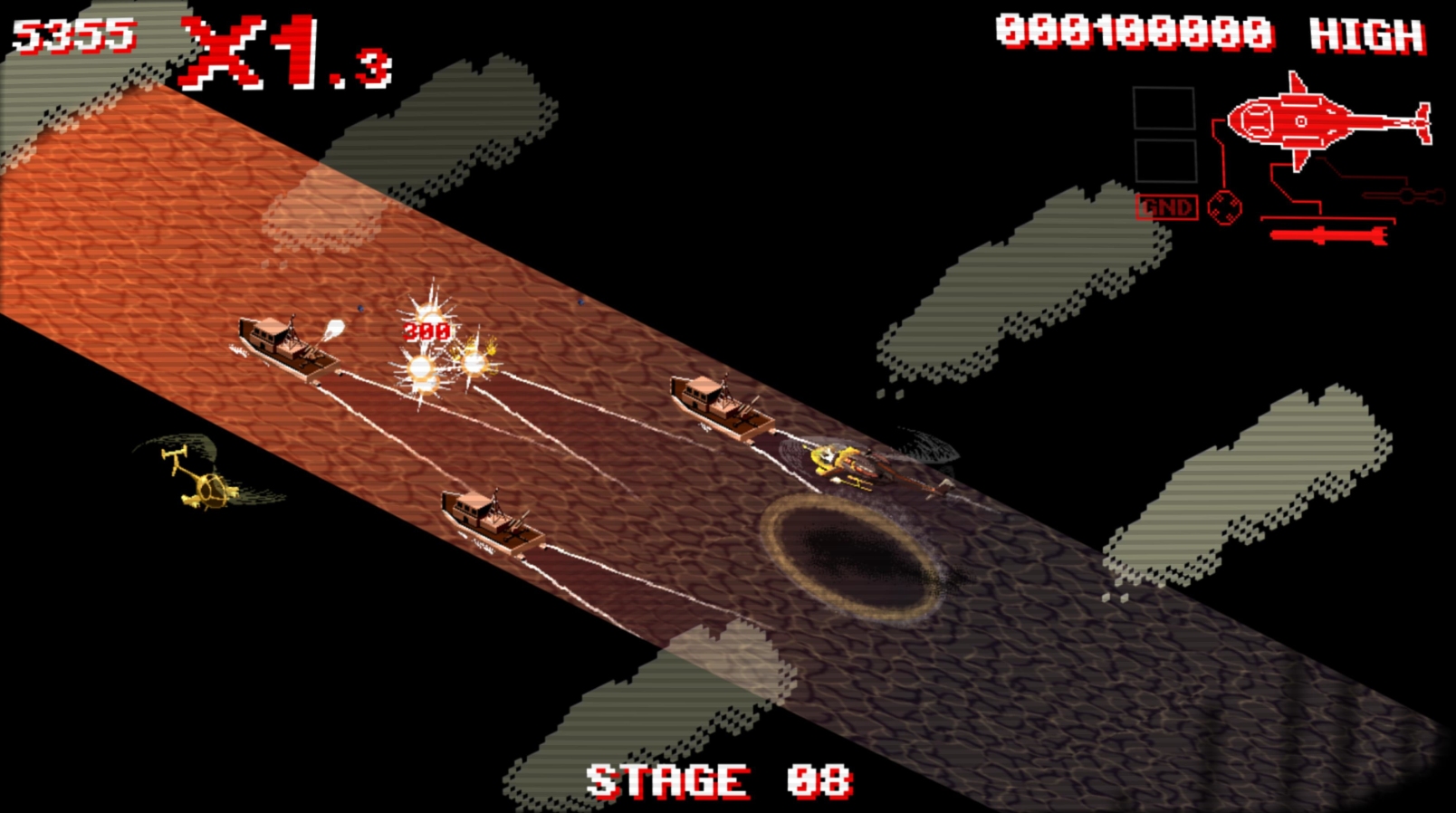

Of course some of our other games (Speed Limit from 2021) had more luck in finding publishers due to their action-packed nature, so we decided to try and focus on more action, and have, in late 2022, received a second grant – to develop a dungeon crawler game, for which we have finished the demo in 2023, but, as mentioned before, the industry completely collapsed and it’s impossible to find publishers to finance anything these days, so the project is waiting for better times.

THC: How easy did you find the application procedure?

Aleksandar: It’s relatively easy but we also have to keep in mind that most indie game development studios are very averse to bureaucracy. It’s also a bit confusing for some people since the commission added XR to games, as some points are only pertaining to VR projects (such as innovative use of cinematography and viewing), if I understand correctly. Now, of course, writing answers to questions is problematic for people who don’t know how to speak “grantese”, the language of these grants. I have been fortunate to be fluent in this language but our industry is mostly comprised of artists and engineers, so I’ve set it as my task to make the grant as accessible as possible to others. I have given many lectures on this grant scheme at home and abroad (mostly in Eastern Europe) and have even sent out examples of winning projects for people to study, helping in my small way to make this grant more accessible to people who might be afraid of the bureaucracy.

THC: How do you think the system could be improved?

Aleksandar: Ranking projects is always going to be subjective, and some good projects might fall out, especially now that the industry has no other ways of financing itself (the record-breaking 255 applications this year, meant you needed 82/100 points to be awarded, so your average should have been between 8/10 and 9/10 for every question). I would suggest adding 10x more money and also opening a special call for production which handles the phase after the demo. The 200.000€ per project is great for small teams in Eastern Europe (if we assume they need two years for a demo, or around a hundred person-months, for an average gross salary of 2000€, which is a bit below the Croatian average national salary, it’s possible, but it needs to be a small team). However, for larger teams or those from richer countries, they do probably have higher co-financing rates as they have access to local publishers, grant systems and other ways of accruing more funds.

THC: Do you think there are better ways of supporting European game devs?

Aleksandar: Money is one part of the solution, always in the back of indie studios minds, but mentoring is another important and often neglected aspect. I would suggest adding a milestone based approach where studios are mentored by experts at these milestones which would hopefully make the final product better and more pliable to find publisher funding for production. Alternatively, setting up mentorship programmes such as the (also Commission funded) Spielfabrique mentoring.

Žilvinas Ledas, one of the founders of Lithuanian studio Tag of Joy, is another dev happy to defend EU subsidies.

THC: Overall, do you think the grant scheme is a good thing?

Žilvinas: Yes, it is definitely a good thing. These grants are not for “develop the game from the start to finish”, but more for “do a preproduction and try attracting more funding and/or publisher with better quality content”. What is more, having such grant also lets you as a developer experiment and try some more obscure ideas, mechanics, etc, and not only try to develop “standard money making games”. I understand that this is a good and a bad thing in itself, but having more diverse and more experimental projects is important for innovating in the medium.

THC: What difference did the money you received make?

Žilvinas: For our company it helped us to develop and finish our first PC and console game. We were quite a young company, so having additional funding really helped us to make a game we wanted to make. Worth noting, that we were, in a way, lucky, that we were planning to make an adventure game where story is an essential part, so funding rules were not an issue for us.

THC: How straightforward did you find the application procedure?

Žilvinas: The first time we were preparing the application it looked quite daunting, but in reality it was easier than it looked from the first glance. In essence, the application procedure can be compared to preparing for a pitch to private investors or publishers. You have to prepare a GDD with enough quality content, target audience definitions, predicted market potential, etc. to convince the experts (who are industry professionals themselves, and any industry professional can join them anytime). A publisher or an investor would want to see all the same things that Creative Europe wants to see, plus a prototype, so these applications are just another way to raise money by pitching to industry professionals.

They might not always be right about the potential of a game so early on, but publishers are very often not either. Most of the games that successful publishers release fail commercially, only around 10–20% recoup the expenses, and maybe around 5–10% are considered successes. I think that’s comparable to Creative Europe’s numbers, having in mind that CD Projekt, 11 bit Studios, Red Thread Games, Revolution Software, Frozenbyte and many other established studios have received this funding to help make successful games and, in the process, keep the IP in the company.

THC: How do you think the system could be improved?

Žilvinas: Firstly, I would like to say that it is improving bit by bit every year – it is better and more sensibly structured and organized now than it was when it started about 10 years ago. Yeah, the requirement to “tell a story” you talked about in the previous post sounds weird. On the other hand, how else could you differentiate really “meaningless games” (my subjective statement)? For example, a lot of hyper-casual or simple puzzle mobile games would qualify if not for the “tell a story” requirement. And I would hate to see those being funded (this is a subjective statement as well 🙂 ).

How it could be improved more? The main issue for us is that you can only have “playable version” (aka “demo”/”vertical slice”/”alpha”/etc) at the very end of the grant period. This has a big impact, as you can’t start various marketing activities with very small playable versions very early on. For example, you can’t participate in various Steam festivals that require to have a playable version. I would think this limitation/requirement could be improved.

THC: Do you think there are better ways of supporting European game devs?

Žilvinas: I’m not an expert here, so I don’t feel I have better ideas 🙂 The one thing I think is important is that all EU countries should be able to participate, no matter how big or small they are.

Lastly, ZaQ Chojecki, co-founder and game director at Warsaw-based Ovid Works, weighs in (Ovid has applied for Creative Europe funding several times, and secured it for VR game Interkosmos 2000 and more recently for the sequel to Metamorphosis).

THC: Did you find applying easy?

ZaQ: The process is in line with other types of EU funding applications. It is a very formal process (The formalism is not very surprising, given that you ask for non-refundable money. A considerable amount too.) and does require time. I personally don’t find it very complex in itself, although some nuances do require knowledge of how these applications work. To tackle that issue we were in contact with the people working for Creative Europe Desk Poland. They were always very helpful, and tried their best to answer our questions, doing some research if needed. There are a lot of instructions and guidelines on the sites too.

As for the tracking and following of the project, we also consider Creative Europe as a very flexible and developer-friendly funding scheme. Other funds we worked with were imposing a lot more auditing, and it was much more complicated to change certain budget or time assumptions (which happens very often during production). As a developer, I really appreciate that they are primarily interested in the final effect of the project and don’t bother with deliverables that would waste a lot of production energy.

There are few issues with the process though. One is the language used, which brings a lot of confusion. See, the program mirrors similar funding schemes for film production and uses film-specific language. The development stage of a film encompasses writing a scenario, and making all the pre-production, castings, shooting test-scenes, mockups etc, in order to be production ready. On the other hand the development stage of the game is the production. But if you look at the language used by Creative Europe, they consider development of the game in the same way it considers development of a film. At the end it should be production-ready. There are a lot of those little confusions. Coming from the film world, I was aware of all these, but I know of a lot of discussions that were needed to clarify this for game developers.

THC: I understand you have reservations about the scoring system too?

ZaQ: The scoring and choice of projects is clearly not efficient. The problem (not an easy one to solve) is of course an institutional one: the European Commission is a very formal entity. A lot of decisions which influence the scores are taken on a policy level, and then try to be adapted to the specific field. For example, ‘greenness’ is quite hard to translate into the worth of a game.

The weighting of the score is also absurd: the whole idea of the game is worth almost as many points as the description of its accessibility options. The scoring approach is debatable: basically what is not written in the project is considered not to exist. So if you don’t mention anything about sound in the project description, the reviewers will assume there is no sound in the game. That’s something that tanked a lot of great projects.

THC: Overall, do you think CE’s grants are a good thing?

ZaQ: These are, of course, challenges. But the programme is also evolving. It is in much better shape than when I first applied in 2016. In my opinion it is also indispensable. Even if only one out of fifty projects make it, it is still the only way to incentivise original concepts, in a field that is strictly money-oriented. Ambitious games are only possible with patronage, and this is what Creative Europe strives to be.

So as much as I have some criticism about it, I still am so happy it exists. I mean c’mon, They let me write a sequel to Franz Kafka’s work 🙂

(To be continued)

Quotes: “experiment and try some more obscure ideas, mechanics, etc”

“the only way to incentivise original concepts”

I go back and forth if this funding should be like Science (publish the outcome, whatever that may be) since, let’s be honest, videogames are neither Art nor Science, they’re Content.

I think I’d be happier (not that I have any skin in the game that I’m aware of) if the industry demonstrated Learning – some sort of awareness of what’s been tried in the past and not come off, and some reasonable hypotheses to explain why not.

Perhaps there should be a European Museum of Ill-Formed Videogames.

“I think I’d be happier (not that I have any skin in the game that I’m aware of) if the industry demonstrated Learning – some sort of awareness of what’s been tried in the past and not come off, and some reasonable hypotheses to explain why not.”

I agree. If you’re going to give a dev 150-200K of public money, I don’t think it’s unreasonable to insist they provide a detailed post-mortem at the end of the project. If Creative Europe had been doing that for the past decade, and the post-mortems were publicly available, the European games industry would now have a useful resource at its disposal.

Well, in a shout out to the even-handedness I originally thought lacking from this story arc, I’m now not sure how I feel about this program in any aspect.

The endorsements these developers offer are neither milquetoast nor cursory — in the context of the author’s original tone and previous criticisms, I’d say they might even approach “ringing.”

Lingering questions remain, for me at least. Among them — ZaQ mentioned the “language used” in a way that appeared to refer to grant criterion, but made me wonder: is this project written originally in French, and then from there translated into languages X and Y?

Does that have an impact?

I’m not suggesting that, in 2024, the EU hasn’t figured out how to communicate with its 27 constituent nations. At the same time, perhaps, in this strange corner of bureaucracy, what is interpretable to our men in Poland, Croatia, and Lithuania, is less so to our man in Blighty? For no other reason than version of this program made available in English is less King James and more Joseph Smith?

Is that a dumb question?

>> I’m now not sure how I feel about this program in any aspect.

While it was illuminating to hear from these three devs, I don’t think their takes invalidate the criticisms levelled in parts 1 and 2. I still feel the programme has major fairness, accountability, and efficacy problems. On Friday I intend to share some critical opinions from wargame and sim devs, propose some improvements, and generally round things up.

The CE’s language stipulations appear to disadvantage smaller/poorer studios. Any studio that doesn’t have a fluent English speaker on its staff could be put off by this paragraph in the application guide: https://tallyhocorner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/eu29.jpg