Today’s article is inspired by an eye-opening conversation I had with a developer pal recently. My friend creates bespoke business software and over the last year has become a firm fan of AI-assisted coding. His enthusiasm got me thinking. Are devs in Grogland and Simulatia coding with the help of AI? Are they using it in other similarly inconspicuous ways? I set about finding out.

My volley of nosey emails elicited some interesting replies. As you’ll discover if you read the following mailbag dump, when it comes to leveraging AI, no two devs working in THC’s bailiwick think alike. For some it’s simply another labour-saving tool. Others are curious, hopeful, or not entirely convinced. One dev I contacted – Radian Simulations – completely shuns it.

Josh: “Radian’s approach to AI in development can be summed up as total rejection. We don’t use it, we prefer our contractors not use it, and we consider it a problem when others adopt it in the game development field. I’ll try to give some context on this.

First of all, the proliferation of LLMs and other generative AI products is an active, top-down consolidation of power by tech capital. These big companies, already unaccountable for how they mistreat both their workers and their customers, are pushing these products in the hopes that they will become a core tool in the work process. That gives them the ability to demand any concession they desire, and it removes the ability for the people doing the actual labor – ourselves – to negotiate that relationship. As one of our members put it to me recently, “AI is an industrial relations issue.”

If the tech bro CEOs have their way, the next generation of game developers (and all other white-collar professions) will be useless without a subscription-based chatbot offering advice. We would rather see our colleagues using open-source tools and their own brains to operate, with full control over the process and the results. This sentiment is shared by plenty of other developers whom I respect.

Secondly, the tools as they exist today just aren’t useful for us. There are tons of glowing reviews from people who are trying to accomplish routine tasks – the boilerplate code spat out by an LLM is generated from dozens of human-authored samples that were doing the exact same tasks, after all. But when you get into novel problems, the tech falls flat. In the occasional testing some of our members have done with AI assistants, the provided answers were atrocious. Believable, cleanly-structured, bullshit code, cheerfully invoking engine features that don’t exist. It took longer to solve problems with this “help” than it would have been without it. Based on some recent studies, I believe this is far from a fluke.

Meanwhile, regarding the easier stuff that vibe coders are impressed by – all of us on the team were educated in the pre-LLM era and know how to search documentation and community forums for solutions. It might take a few seconds longer than ChatGPT or whatever, but at least it’s concise, it’s delivered by a person who’s actually done the task, it usually comes with a follow-up discussion already available to peruse, and if someone lies on a code forum they’ll be downvoted to hell. Plus it’s worth remembering that the LLMs are trained on this exact internet content in the first place. Why ask a bot to generate a statistically weighted facsimile of an answer when you can just read the source text?

Finally, a personal note: I’m not a hater just for the sake of hating. I hold a Computer Science Engineering degree and love machine learning and all the cutting-edge stuff happening in the broader AI field. My understanding of how this stuff works makes me even more confident in saying that generative AI is overhyped nonsense and we don’t need it. It’s structurally unsuitable for the role it’s being sold for. They’ll never make an LLM that doesn’t hallucinate, and if they did, they’d never deploy it in a way that doesn’t empower some turtleneck dipshit at the expense of ordinary people.”

Giant Flame’s concerns about coding with AI assistance seem primarily practical:

Tom: “Yes, I do use AI when developing. I am working from a large and quite solid (human written) codebase and generally making fairly small additions or bug fixes. In both cases I use AI by feeding it scripts and describing certain features in the game and how they work. Then I ask the AI to find the relevant code in the scripts and explain to me how they underpin the feature(s) I have described. Once it has done so to my satisfaction, I describe the bug or new feature and ask it for options in how to address it. This request is accompanied by a LOT of guardrail statements (I do NOT want to affect this/that and the system must still this/that) and a request for solutions that are as “safe” as possible and require minimum changes possible.

Once solutions have been provided I ask for a breakdown of the code changes in diff format with line by line explanations of what has changed and why. Then I pick a solution and test implement it.

Anecdotally, Claude seems to process the existing codebase better and grasp the issue/request quicker. Grok seems to produce more thorough solutions.

Many issues I have encountered with AI dev could have been avoided by improving my own prompts. Sometimes they were due to the AI’s own input restrictions, but that usually just meant I needed to pay for a higher tier of AI resources. It is not always clear this is the issue, however. As with everything, we learn.

Overall, it is indeed a big boost in productivity. That said, I would NOT want to be developing a large new feature or system using AI currently.”

Another fairly satisfied AI user is Oskari, the chap behind one of my favourite rail sims, Diesel Railcar Simulator.

Oskari: “I use AI for solving all kinds of problems because it’s good at answering questions. Sites like Stack Overflow often appear in the references so I usually visit them anyway, simply to verify the answer. The code examples produced by this kind of AI are too generic or incorrect to be useful though. I don’t use proper AI coding assistants because of copyright and privacy concerns.

I also used AI to translate Constracktion. While some players noticed errors, it didn’t seem to bother them too much because the game isn’t text heavy. Others were happy to find any kind of translation to their language, even a machine generated one. I’ve made some corrections based on player feedback but all of them have been relatively small. Outsourcing to human translators is hit and miss since some of them use AI anyway, only checking the output for superficial errors. The original context and semantics may be lost but it’s hard for me to tell since I don’t know the language.

2D art asset generation is another (very controversial) domain where AI could be useful but I haven’t made any attempts to create anything. Other devs have, sometimes with backlash from players.

There is one AI generated art asset in Constracktion though. I was looking for desert skyboxes but most of them were captured near inhabited areas, until I came across ones that seemed to have been photographed in a remote location. They turned out to be AI, something the store description failed to disclose. I hesitated to include them in the game but finally decided to use one to see what the reaction is (there hasn’t been any) and because it was rather pretty. AI in this particular case is unlikely to replace human labour since few people have the opportunity and willingness to take a drone into the middle of a hot, remote desert to capture sky textures.”

Talking of drones, here’s what Kevin Haelterman, father of Liftoff and Liftoff: Micro Drones, had to say on the subject of AI assistance.

Kevin: “No, we currently don’t use AI extensively in our development processes, our game assets and code are still mostly original work. When we do, it’s on an individual basis rather than through a structured, integrated workflow. Most of our work is still done manually. The AI tools we use are usually some built-in smart features, like in software such as Photoshop, or simple utilities for checking text or code, essentially advanced spelling or error checkers. In those cases, there’s always still a human involved.

We understand that AI is a hot topic that often triggers strong reactions, but in game development not all of us see it as the dramatic revolution some claim it to be. Our focus has always been on streamlining our workflow, improving quality, and staying ahead of rising development costs and user expectations. As games become more complex and visually advanced, development becomes more expensive. As a small company, we rely on smarter, more efficient tools to keep things manageable without increasing production costs (and by extension, the cost to players). This isn’t new or unique to AI, this evolution is as old as the industry. We are not afraid of change.

Our industry has always evolved at a rapid pace, with toolsets improving year after year, even long before AI. Workflows change constantly, and tasks that were essential one year can be completely replaced by better tools the next. We don’t see this as tools replacing developers; we see it as tools enhancing their capabilities so they can focus on what matters: creativity, innovation, and meeting new user expectations. When I was a student, I learned how to model 3D trees by hand. Then tools like SpeedTree, long before AI, automated that entire process, making my original training obsolete and forcing me to rethink how I could contribute. That cycle never ends. Developers keep learning, adapting, and evolving.”

For Scott Goffman of Panic Ensues Software, AI has yet to prove its worth.

Scott: “As a solo developer, I’m very excited by the potential for AI to increase my productivity. But the reality is that, for me at least, so far it has been completely useless.

Let’s talk about the art production side first, as that is by far the biggest consumer of man-hours, and thus where I could use the most help: At this point, there are no AI tools available that will produce game-ready assets.

Okay, fine, but could they at least create, say, a 3D model that I can use as a starting point? In my experience: Nope. What they can create is a model with inaccurate proportions/features, insane poly counts, no clean topology, and no consideration for texture mapping. Cleaning up their work takes longer than just starting from scratch with good reference images.

Well, since almost all of the development in AI art creation is in 2D images or videos, they must at least be helpful for creating concept art, right? Again, no. I’ve found them to be good for nothing beyond creating slop for social media. In my experiments with tools like Stable Diffusion, DeepAI, and Perchance, 90% of what they create is still too deeply flawed (e.g. too many fingers/arms/legs) to be usable. And the remaining 10% highlights the fact that these systems are incapable of actually creating anything: All they can do is consume and digest existing media (“training data”), then smear it together and regurgitate it, so you’re effectively guaranteed to get something unoriginal. In fact, statistics dictate that you’ll get a melange of whatever has previously been done the most.

So let’s move on to the code side, which seems much more promising. I do have peers in the industry who swear by AI as a code assistant, but again, my experience with this has not been great (though better than on the art side, low bar that it is).

Most experienced programmers will agree that letting AI write an entire module (let alone a whole program) is a terrible idea, as you’ll then be stuck debugging, maintaining, and modifying a code base built without any notion of future work or expansion.

But for creating stand-alone functions, AI should be great, and this is the usage example I always hear about from industry friends who love it. But once again, my experience with it has been, for the most part, terrible. Why? It’s not reliable. When I ask it for a particular function, it will usually deliver something that looks exactly right. But all too often, it’s either misunderstood the task or is just plain lying (oops, I mean “hallucinating”) about the results.

Here’s a specific example: My trigonometry skills are non-existent, and I needed a function that would find the largest possible axis-aligned rectangle that would fit inside a rotated rectangle. I trawled all the usual forums (StackOverflow, Github, CodeProject, etc.) and found lots of examples of how to calculate the outer bounds of a rotated rectangle, but not what I needed.

So I turned to AI, and started feeding the prompt to the various AI code generators. Over and over, they would each misinterpret the prompt, no matter how many different ways I phrased it, as a request for the outer bounds of a rotated rectangle. Finally I found one that seemed to clearly understand the goal, and proudly and confidently delivered a function, with comments claiming it was doing exactly what I wanted. But on running tests with that function it turned out to be, sure enough, calculating the outer bounds.

So I guess the bottom line for me is this: Since I can’t trust the results from AI, whether they’re c# functions or answers to research questions, then I must always manually check its work, which eats significantly into the time that would otherwise be saved by using it.”

While Robert Pietrzko of DeGenerals has also uncovered the limitations of contemporary AIs, he has found them useful for producing Tank Squad concept art and voice-overs.

Robert: “Speaking personally as a programmer, I’m not using AI for problem solving, but I see why others do and my other programmer uses it a lot and I see his performance rising when he does.

The software I’m using to code is Visual Studio 2022 which has options and a bunch of additions to enable AI overwatch and a prompt to ask for help here and there. Although I’m not using any of that, the program still suggests code, expecting that its suggestion is something I’ll want (and mostly it it, like a one button line fill out with expected code etc.)

But when it comes to heavier topics like how to solve ballistics projectiles going through armor without detecting it in multiplayer due to lag, then I don’t really know if AI can solve things like that right now. Or when I’ve 20-30 tanks in action at once with full physics and would like to optimize even further, I doubt a question to an AI companion will really prove helpful.

Maybe there are other fields where such companions excel and makes the programmer’s job easier and faster, but having looked at examples, I’ve yet to see them.

When I am using AI it is in two places:

1. Grok or similar AI image generation to design scenes with weather and lighting etc. for level designers when the level is missing or in progress and I need to visualize my idea. A good example here is how I wanted the Ponyri campaign to look. With a few prompts I generated an image for my level designer and level artists so they could get underway with this vision in mind.

2. Voice-overs. We needed voice-overs to fill in gaps as our previous attempts to record them ourselves didn’t go well. My flaws in English and German as well as my microphone, and mumbling delivery etc. left me searching on Fiverr or other portals for professional actors. This led to a few meetings with potential actors which went nowhere, as we couldn’t afford their fees and the demo festival where our game was to be shown was getting closer and closer.

At that time, we still were in PlayWay, and other devs were using small-scale AI voice-overs for filling gaps. Shown the software, we created a few lines, which were good enough stand-ins. We planned to use real actors later when more money was available.

Since then the actor issue has repeated itself a few times, our financial situation has deteriorated even further and we’re still using AI voice-overs. I am really impressed by GHPC’s and Easy Red 2’s voice-overs. For the latter, my friend Marco worked hard, got the game to be profitable and just recorded everything with real life actors.

So to sum up, my approach to AI is to use it as a design aid or for temporary assets that will later be redone by real people. Big companies invest and use the AI more and more where we as indies won’t be able to outrun them – which we don’t really have to do. Without the top priority of increasing sales with every game every year, we can focus on the game itself and just use the AI when we have problems. The big fish, on the other hand, seem to have a different approach and replace real developers with AI 🙁

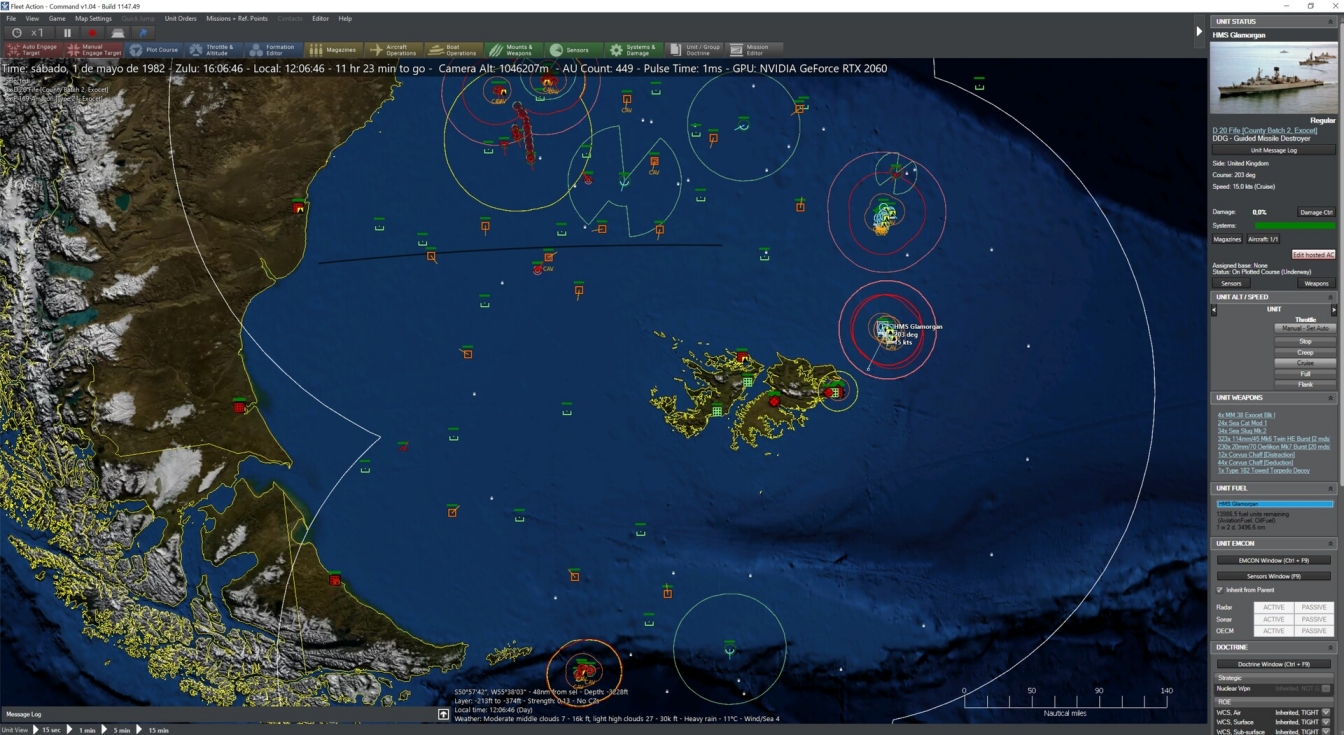

With one exception, all studios working under the Slitherine banner, refrain from using AI to generate art and audio assets.

Marco Minoli: “We use AI strictly as an internal efficiency tool to enhance our workflow. It helps streamline processes, rapidly iterate ideas, improve internal documentation and text, and allows for faster task management. It is integrated as a company-wide efficiency layer. We do not use AI to generate in-game assets or any player-facing content. All creative elements that players interact with are created by human developers and artists.

The only current exception is the game Shadow Empire, developed by VR Designs. The solo creator of that complex product is experimenting with AI tools to accelerate and manage the delivery of updates, especially on the art side of things.

While we recognize the importance and potential of AI, we believe it’s currently too early to make business decisions around its extensive use in content creation, especially given the current regulatory landscape. We feel there is scarce and imprecise regulation concerning the legal, ethical, and social implications of using AI-generated content. There is no cohesive, industry-wide view on what is legally acceptable and how AI will impact the livelihoods of people in our industry.We are committed to making decisions based on established rules, regulations, and morally responsible behavior, rather than simply following current trends.

There are also areas where Large Language Models could massively help wargames being more widely appreciated, and we’re working towards using these to give a wider potential audience to our more complex products.”

Only one of my respondents, Amiral Crapaud of Drydock Dreams Games, said they used AI to aid with historical research.

Amiral Crapaud: “My reply will sound a bit overconfident, but the reason why our dev JB doesn’t use AI is because he doesn’t need it. He has developed so much experience over the years that he has reached a point where an AI would be unable to code for him faster, prompt included, than when he’s coding manually.

On the other hand, if I had a dev that needed assistance from AI to code, I would have no issue with that, considering the human factor is still in play. Myself, I have taken a liking to using NotebookLM for my history research, as it is able to fluently work on non-OCRed American reports or even Japanese historical records. It helps me in ways Acrobat Reader alone never could.”

Sometimes, as Johan Nagel of Every Single Soldier reveals, the inherent simplicity of a project renders a virtual coding assistant unnecessary.

Johan: “I wish I knew how to use AI in the game development cycle (old dog, new tricks…). I really think I need to investigate it but would rather be shown than do the hard yards. I have been meaning to talk to my technical artist to get me started.

The game I’m working on right now, Carrier Deck 2, is very simple from a coding perspective so I can’t see AI would make a big difference.

However, with the COIN series it could potentially earn its keep.”

Although far from scientific, this ‘survey’ is, I think, quite revealing. While something approaching a consensus seems to have developed when it comes to using 2D generative AI art in games, the situation is much blurrier when the question is broadened out to AI in general.

For small outfits, an AI coding assistant that could be regarded as a job-stealing interloper in a different context, might allow a hard-pressed indie to stay competitive, up their ambition, or devote more time to the aspects of game creation they most enjoy. Right now, silicon factotums clearly require careful guidance, and even then may end up botching assigned tasks. However, that situation is likely to change in coming years. Will the day ever come when coding purists advertise their games as ‘artisanal’ or ‘handmade’? I wouldn’t rule it out. Such labels, if trustworthy, would allow customers concerned about the environmental or industrial impact of AI to purchase games without fear of worsening the climate crisis and empowering and enriching “turtleneck dipshits” in the process.

Would you prefer to buy games coded ‘the old-fashioned way’ or are you happy for devs to cut corners with the help of AI? I’d be interested to hear your thoughts on this topic, and I imagine the devs kind and candid enough to share details of their work practices with Tally-Ho Corner, would be rather interested too.

Moderately ironic, given that for decades (war)games have been sold describing the CPU opponent as an AI.

I suspect most devs over that time, particularly those holding degrees, will have gritted their teeth at the marketing hornswoggle, understanding there’s mostly dumb stuff under the “AI” umbrella.

I guess my follow-up question would then be: if you could include a genuine AI as the silicon adversary for the human player, would you?