Depending on your perspective, the small South African engagement I’m about to describe either never happened or happened six times. It either claimed the lives of hundreds of soldiers or it claimed the lives of none.

My copy of Carl von Clausewitz’s On War hasn’t been touched in several years and, I’m ashamed to admit, has never been read from cover to cover. My edition of Sun Tzu’s The Art of War wears a mantle of dust almost as thick. If both of these ‘classics’ were as pithy, amusing, and relevant to wargaming as The Defence of Duffers Drift, they would definitely see more action.

Written by a chap called Ernest Dunlop Swinton in 1902, the brief* and whimsical DDD was aimed at junior officers in the British Army. A veteran of the Second Boer War, Swinton had seen first-hand how ill-prepared for ‘modern’ warfare many young officers were and decided to help out by penning a tactical primer free of guff, pomposity, and outdated advice.

*70ish pages

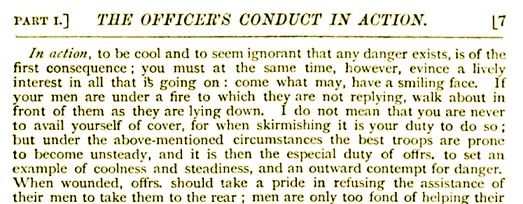

Compared to the dry field service manuals and encyclopaedic soldiering guides of the time (The pics above and below are from General Viscount Wolseley’s (K.P. G.C.B. G.C.M.G) The Soldier’s Pocket Book of 1886) Swinton’s slim tome is wry and laser-focused. Instead of lecturing the reader, or burying them under pointless facts and figures, the author opts to win them over with a flawed ‘hero’, an intriguing premise, and a panoply of silly puns.

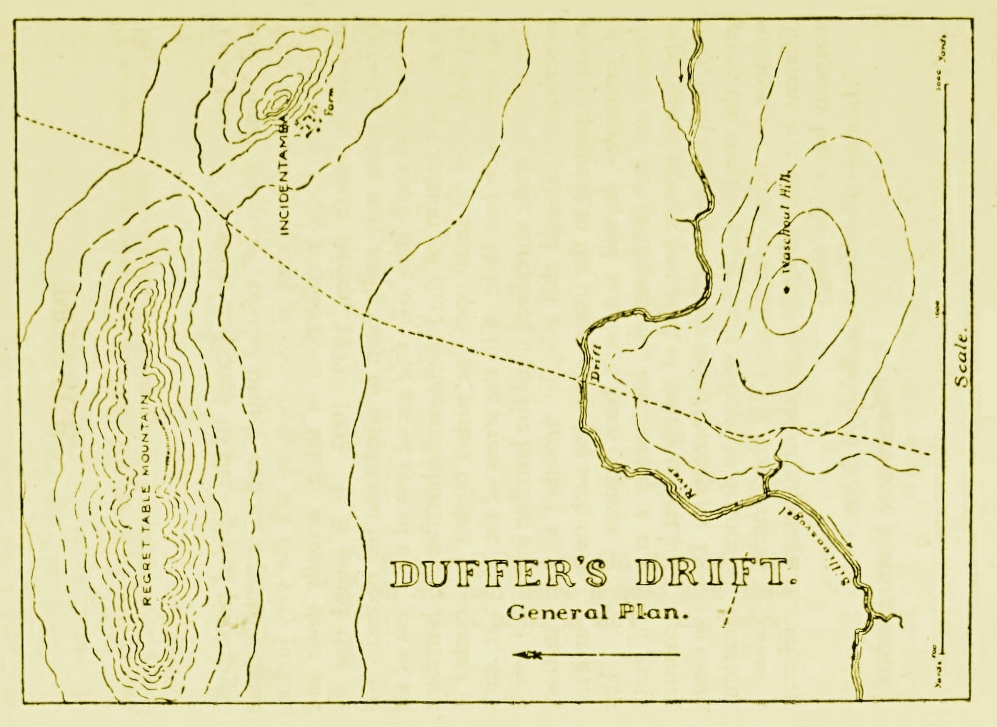

After a long trek green-as-grass Lieutenant Backsight Forethought (‘BF’) falls asleep and dreams he has been tasked with organising the defence of a crucial ford on the ‘Silliaasvogel River’.

He has fifty men at his disposal, orders to hold the drift “at all costs”, but no real idea how to tackle things…

“The more I thought, the more puzzled I grew. The only “measures of defence” I could recall for the moment were , how to tie “a thumb or overhand knot” and how long it takes to cut down an apple tree of six inches diameter. Unluckily neither of these useful facts seemed quite to apply. Now, if they had given me a job like fighting the battle of Waterloo, or Sedan, or Bull Run, I knew all about that, as I had crammed it up and been examined in it too. I also knew how to take up a position for a division, or even an army corps, but the stupid little subaltern’s game of the defence of a drift with a small detachment was, curiously enough, most perplexing.”

In Dream #1 he chooses a spot close to the drift for his camp and sentries (“as every one knows, if you are told to guard anything, you mount a guard quite close to it, and place a sentry, if possible, standing on top of it”), decides to postpone the digging of trenches until the following day (his men are tired and being “good British soldiers” dislike navvying), and reconnoitres the surrounding area, meeting a family of friendly Boer farmers who subsequently visit the camp to sell milk, eggs, and butter. Told by his superiors and guests there are no foes within a hundred miles, he turns in relatively content. The sound of the bonfire-comforted sentinels calling to each other at half-hourly intervals bolsters his peace of his mind.

I won’t insult your intelligence or spoil the story by telling you exactly what happens in “the grey of dawn” the next day but, unsurprisingly, BF’s defensive preparations turn out to be less than optimal.

At this point in a less imaginative tome the writer would simply explain what his protagonist had done wrong and his students would disperse a tad overwhelmed but a fair bit wiser. Having a multitude of other pitfalls to signpost, Swinton, however, takes a different path. BF immediately has a second dream in which he remembers and applies the lessons of the first. In Dream #2, trench digging begins immediately, sentries are silent and forbidden fires, and locals are not permitted to approach the camp (there are other tactical improvements too). Once again BF retires to his tent pretty happy, only to be thrust into uncomfortable introspection the following morning by a hail of incoming rifle fire.

It takes BF six dreams in all to finally figure out how to hold his objective. Each of the five failures teaches him, and us, something new. While a few of the book’s insights will seem obvious to modern soldiers and grognards, and some others have been rendered obsolete by technological changes, DDD is a book that still has plenty to offer the 21st Century warrior and wargamer.

By chance Swinton foreshadows contemporary computer wargaming almost perfectly. Looking on as BF trial-and-errors his way to victory, armchair generals are sure to feel a sense of kinship. His dreams are our mission/scenario attempts. He falls asleep again after his camp is overrun, his trenches enfiladed, and his men slaughtered. We press ‘restart’. He gets to know the enemy’s tendencies and tricks by watching them adapt or fail to adapt, just as we do. BF doesn’t know it, but he is probably literature’s first wargamer.

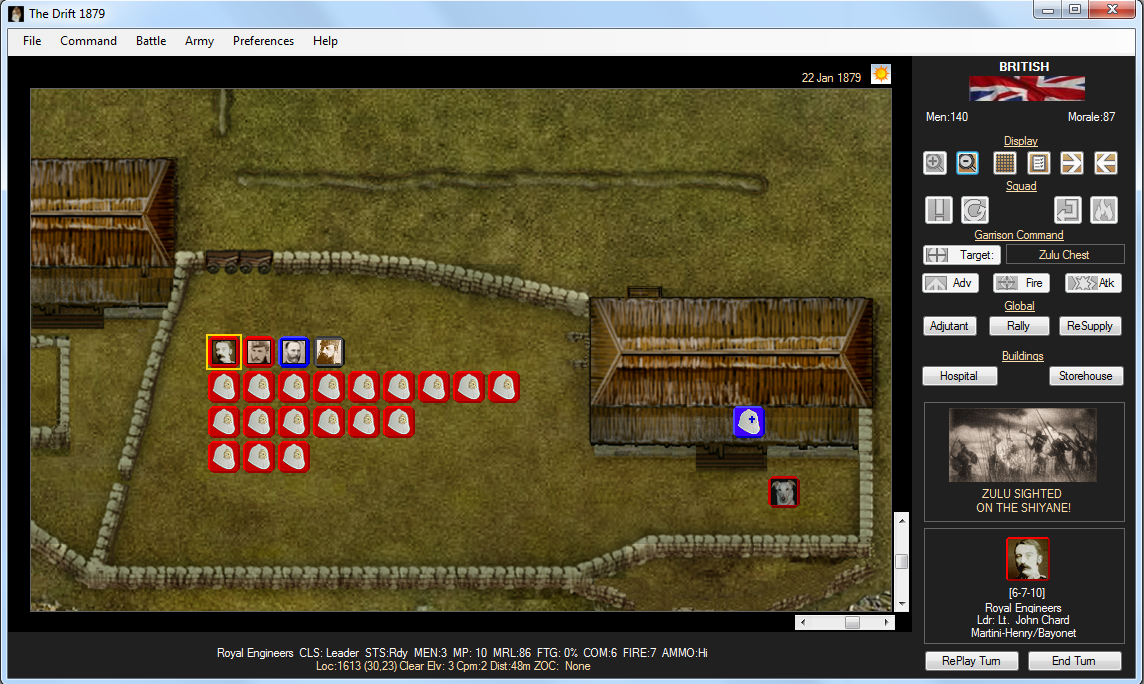

As a spoilerific strategy guide for it has been available for over a century, a wargame that perfectly recreated the defence of Duffer’s Drift would be fairly pointless. However, that doesn’t mean the book couldn’t or shouldn’t influence the genre it unwittingly echoes. I can’t read Swinton’s survival guide without pipedreaming wargames with defence design and organisation at their cores. Military history is littered with examples of badly outnumbered forces successfully holding forts, farms, hills, mountain tops and the like, but on the few occasions these thrilling scraps have been turned into code, proceedings generally start moments before the first bullet, shell, arrow or assegai flies.

Yes, occasionally we get to hand-deploy troops and decide where trenches and wire should go, but where are the wargames that put us in BF’s boots, and ask us to design defensive positions in detail? During the Lieutenant’s final dream he, amongst other things…

- oversees the construction of rifle pits and trenches, incorporating natural features where possible to save time/energy

- orders the the erection of abatisses and the removal of cover-affording scrub

- has his men set up inconspicuous ranging markers

- selects loophole positions

- inspects camouflage

- checks for possible skylining

- organises and positions water and ammo reserves

- rounds up locals to prevent them warning the enemy of the British presence

- ensures his NCOs have a clear understanding of his battle plans

In short he works his puttees off. It’s not hard to imagine a game in which a time and manpower short player is asked to turn a vincible position into an invincible one. What is more important – constructing that communication trench between the barn and the chapel, or ensuring the ravine in the north-east is blocked by a thorny barrier?… Depopulating local farms will take ages, lose ‘hearts and minds’, and mean a few of your men must spend the scrap guarding prisoners not fighting off attackers – is it really worth it?… Because your map is far from perfect, you need to thoroughly scout your surroundings in order to identify every patch of ‘dead ground’. Can you spare the precious time?

There’s no reason why a DIYD (design-it-yourself defence) wargame couldn’t be set in almost any era. Watching footage of Ukrainian troops clearing trench networks, it’s plain that Swinton’s advice on things like camouflage, cover, fields of fire, silhouetting and misdirection, is ageless.

Distributed to British junior officers in 1944, and the inspiration for a clutch of other tactics tomes, the Defence of Duffer’s Drift has undoubtedly had a greater influence on warfighting than wargaming. Unless some BF with vision, coding skills, and funds, notices the book’s considerable ludological potential, that strange inconsistency will continue.

Now that’s a fascinating idea…

I’m no wargamer, but I have to say: I don’t know; you’d always be up against the vagaries of the game engine.

3D engine & percentages (whether hidden or visible):

oops, you placed whatever 1m too high/low on the slope, and now its’ concealment is 23% as opposed to 76%.

Hexes:

risks turning into a puzzle game/figure-out-what-the-scenario-designer-expects-you-to-do if the optimal solution is always to build a foxhole in e11.

Ultimately, and for purposes of replayability, you’d want a unicorn AI that can generate novel and varied ways to attack.

“You’d want a unicorn AI that can generate novel and varied ways to attack.”

Agreed. A DIYD game with a predictable or suicidal AI would be pointless.

“Hexes: risks turning into a puzzle game”

I think that pitfall is eminently skirtable. Imagine, for instance, a game in which after you’ve decided to dig a trench in a particular hex (or along a particular hex edge) you then have the option of improving the trench in various ways. Precious ‘MH’ (Man Hours) could be spent boosting its cover value, or its concealment, or even increasing the number of in-LoS hexes its occupants could fire upon (‘Loophole Creation’?).

Combine this sort of depth, with inventive AI, and random maps, and things start getting really interesting!

The Defence of Hill 781 is the modern version of this book based around the same premise but set at the NTC around a mechanised defence against a soviet motor rifle regiment. I think it stands up pretty well despite being somewhat dated. I think the key lesson is you can deny terrain rather than hold ground.

This jogged a memory of mine: John Antal’s choose-your-own-adventure command books, which I almost fully explored before finding the right paths, when I came across them on my high school history teacher’s bookshelf.

Infantry Combat: The Rifle Platoon is probably the nearest to Duffer’s Drift in a number of ways.

Thanks for the tip. I’d not heard of this series. A THC review of Infantry Combat: The Rifle Platoon before the year is out is highly likely.

Thanks for mentioning this! I really enjoyed Duffer’s Drift and Hill 781 is an interesting take on a more modern and higher level command situation.

And thanks to Tim for the original article. It’s amazing how well certain older books stand up to the test of time!