I’ve never played a wargame quite like Maestro Cinetik’s latest TBS before. Yes, there have been moments this week when, moving armies from Chinese district to Chinese district, I’ve been reminded of AGEod titles such as Birth of America and Revolution Under Siege, and occasions in the midst of political, social, or economic engineering when memories of Paradox creations such as Crusader Kings and Europa Universalis, have surfaced unbidden, but Rise of the White Sun has qualities and character all of its own.

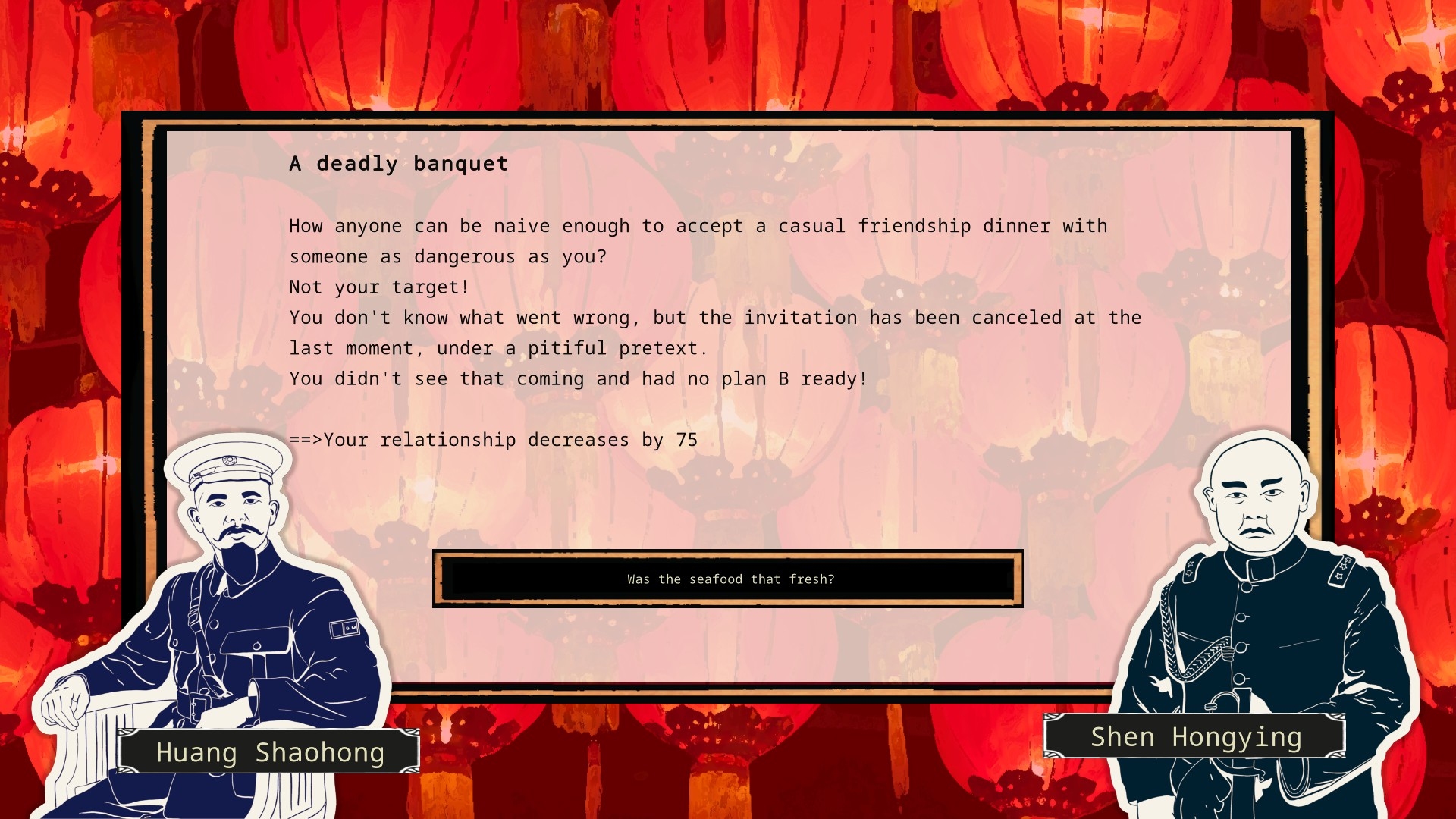

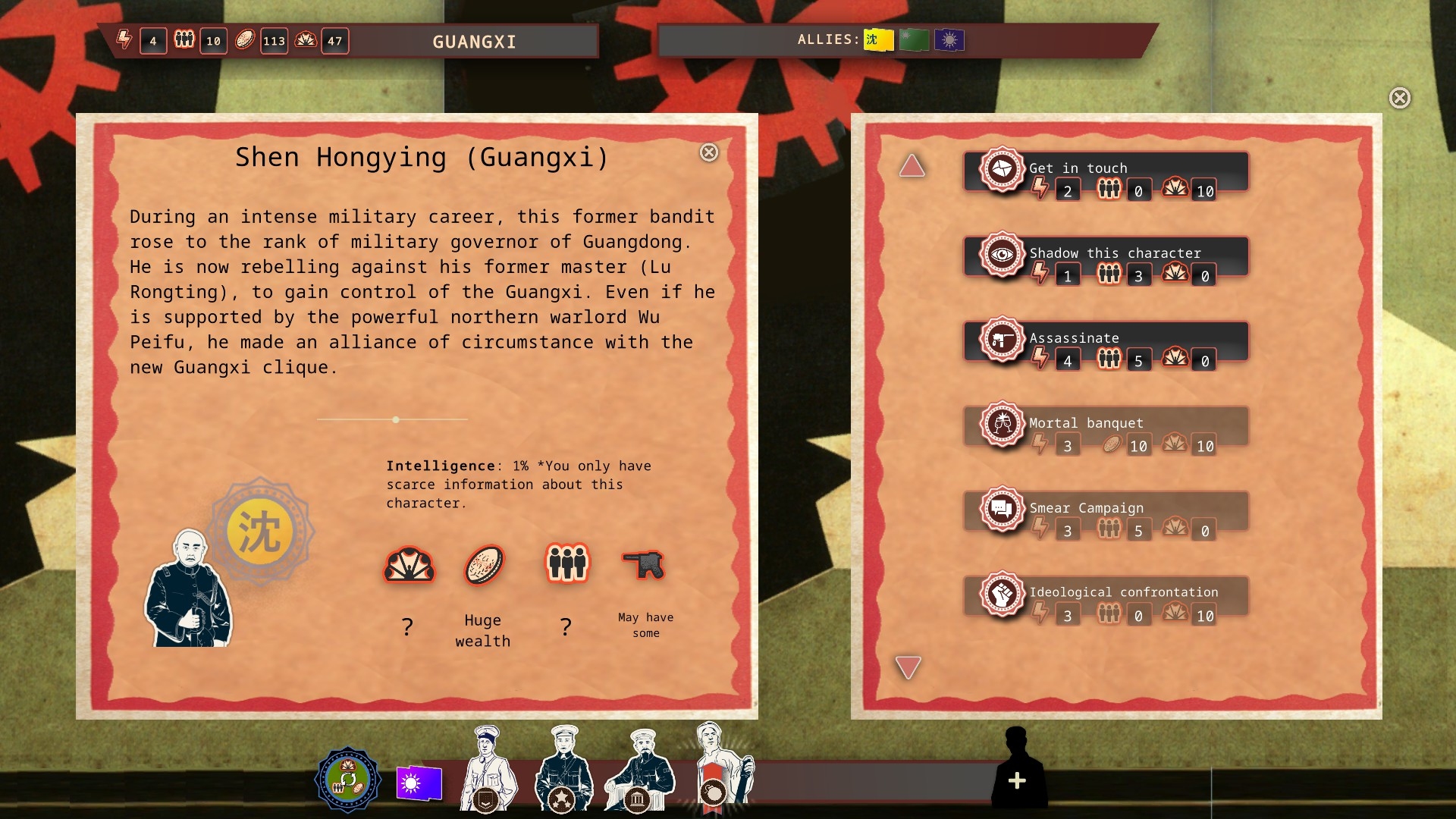

Last night for instance, while tussling for control of Guangxi in one of the game’s smaller scenarios, I attempted to eliminate a powerful ‘ally’ by feeding him poisoned grub at a banquet I’d organised. When this murder attempt miscarried I hired an assassin who eventually got the job done with an infernal device.

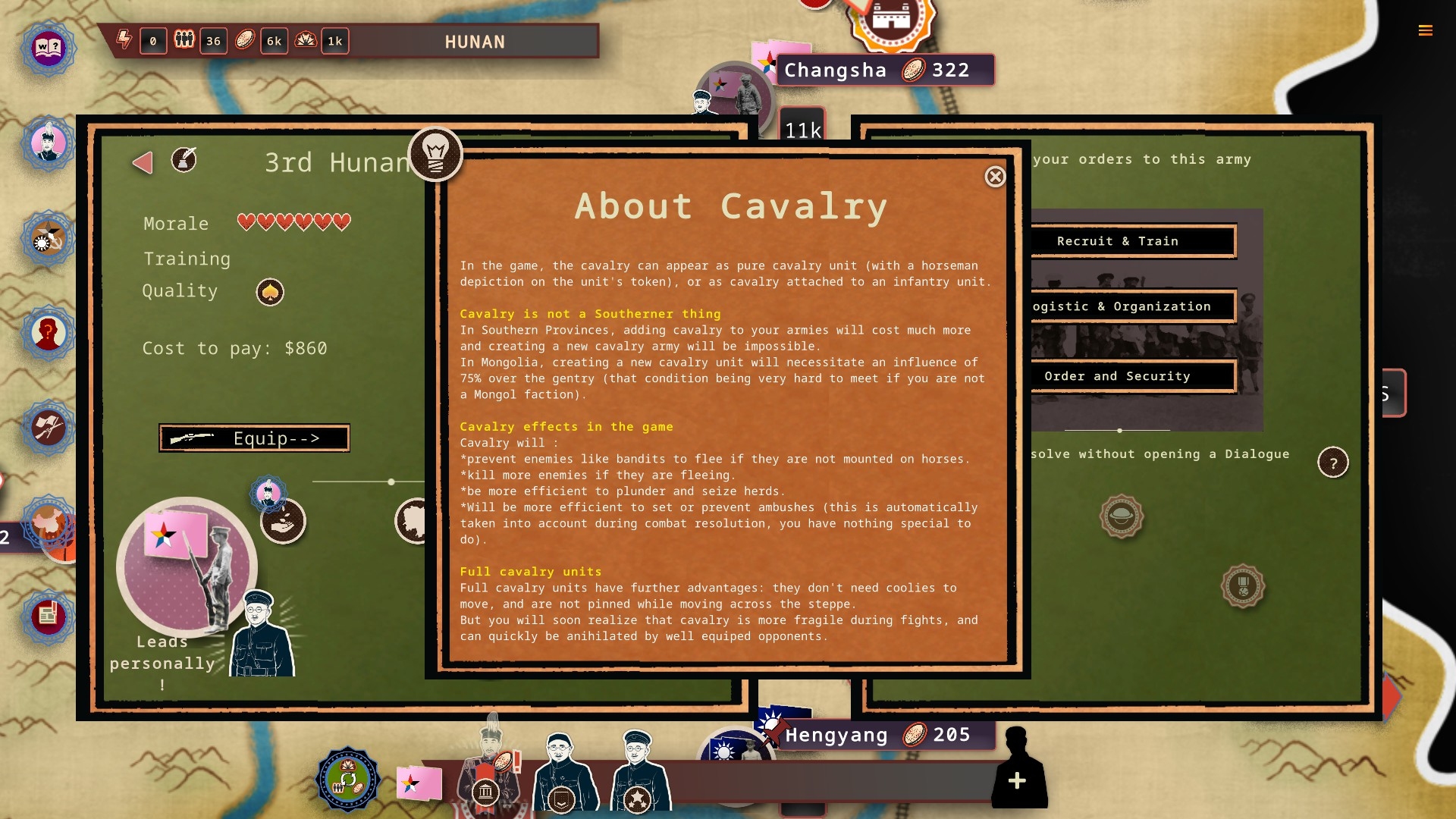

If I’d been painting Guangxi purple (my goal) in a title like Wars Across The World, my brain would have been fully occupied with questions of army composition, position, supply, and leadership, as I played. While these concerns were never far from my thoughts in RotWS too, they often jostled with a swarm of less familiar considerations.

Should I deal with my bandit problem in the west with bullets or bribery?

Should I turn to gun runners to help solve my rifle shortage or invest in a fledgling arms industry?

Before I confront that large force in the south perhaps I should undermine their loyalty with a rumour campaign.

Which of my armies should get the five artillery pieces I’ve just liberated from the enemy?

In order to pay my increasingly disobedient main army, should I start looting the Buddhist temples in my territories?…

Armies in RotWS are splendidly unreliable organisms. Led by ambitious officers, prone to homesickness, and sometimes enervated by the curse of opium addiction, they pillage if you fail to feed or pay them, and may desert, switch sides, or turn to banditry if conditions get really dire. Although accurately assessing the loyalty of your men is made deliberately difficult, thankfully it is possible to invest in actions and organisational improvements that make it easier to spot and stop mutinies and defections before they happen.

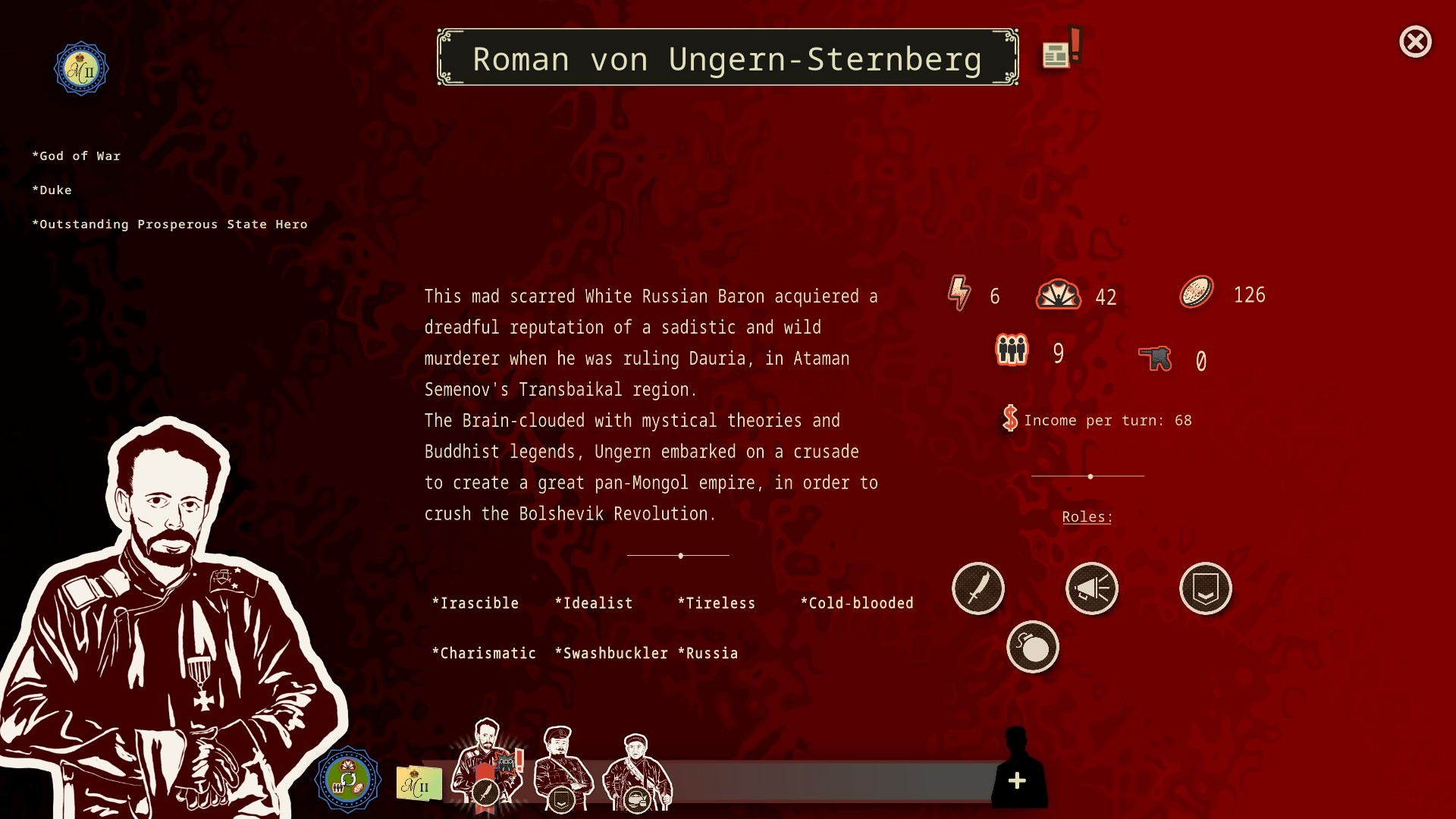

Perhaps the game’s most unusual feature is the importance it places in ‘characters’. The stylish portraits displayed at the bottom of the screen are likenesses of the most powerful personages in your faction. Characters have their own talents, flaws, roles, regional affiliations, and assets, and it’s through them that you issue all orders be they military, political, diplomatic or economic. Because orders cost one or more of the game’s four resources (Qi – “vital energy”, Supporters, Money, and Face) to execute, (one session of resource redistribution is permitted per turn) and may not be available to everyone in your staff, deciding how to spend each bigwig’s Qi points each turn is rarely easy.

Some characters have the ability to boost battle chances by personally leading armies (Obviously this option isn’t without risk. In some scenarios the death of a particular figure brings automatic defeat).

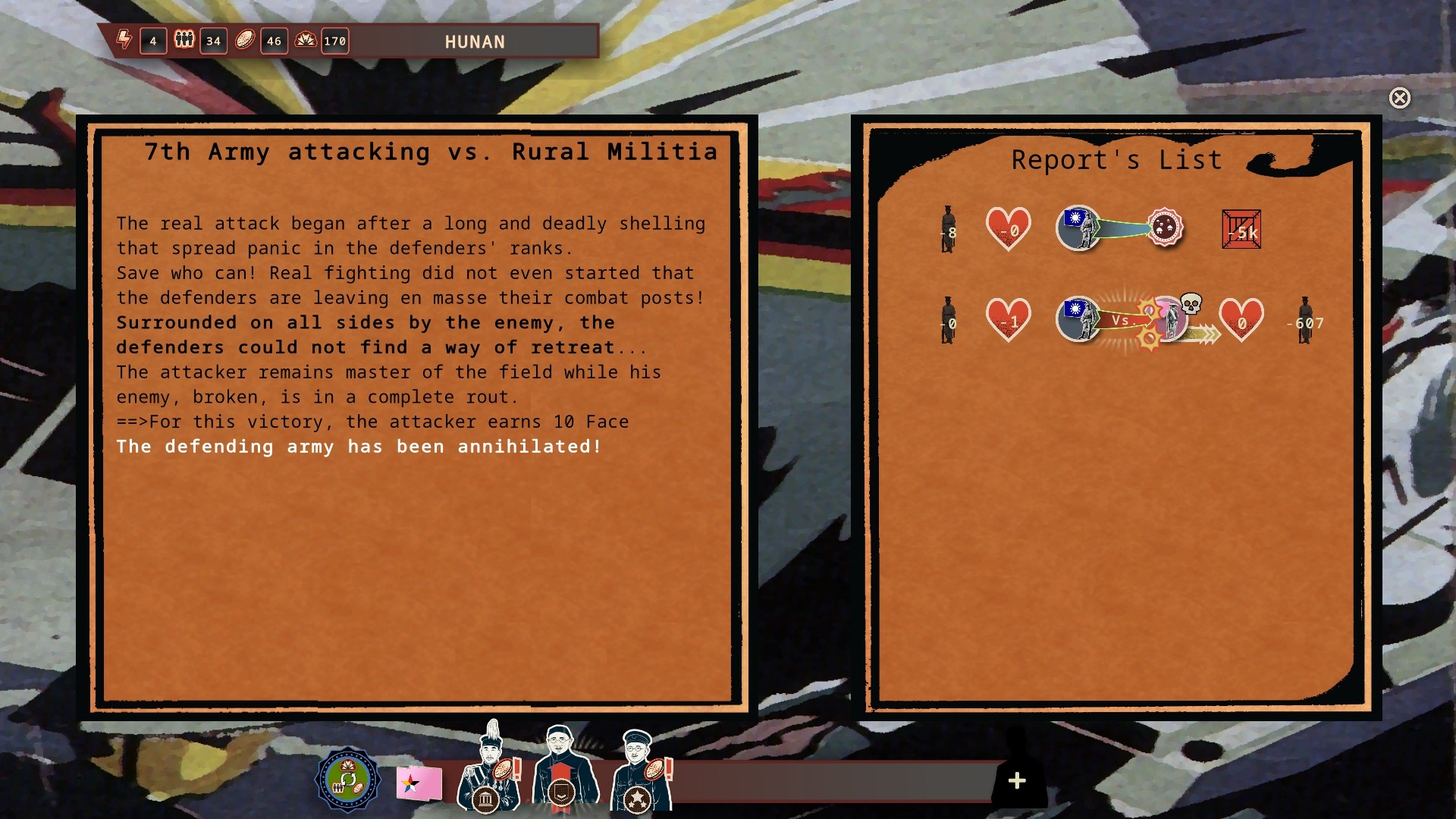

Would it have been nice if using one of your precious VIPs in this way not only influenced the game’s hidden combat algorithms, but opened up AGEod-style tactical options (probe, attack, assault…) too? I think so. One of the few criticisms I can level at RoTWs after around ten hours of rapt play, is combat decisions are essentially binary. Should I take on the enemy force in the neighbouring province now, or should I wait a turn or two until I’ve enlarged, trained-up, better equipped, and assigned them more ‘coolies’? There’s no ability to modulate aggression.

Maestro Cinetik have used the Early Access year well. What was once a rather baffling and overwhelming plaything is now, thanks to myriad advice pop-ups and tooltips, an embedded encyclopedia, and a slew of small beginner scenarios, far less intimidating. Visually vague district boundaries in some provinces sometimes confuse unnecessarily and the order menus would benefit from some light reorganisation (Bizarrely “training troops” is found under Organisation & Logistics not Recruit & Train), but all-in-all the UI and icon-strewn maps are logical and simple to parse and navigate.

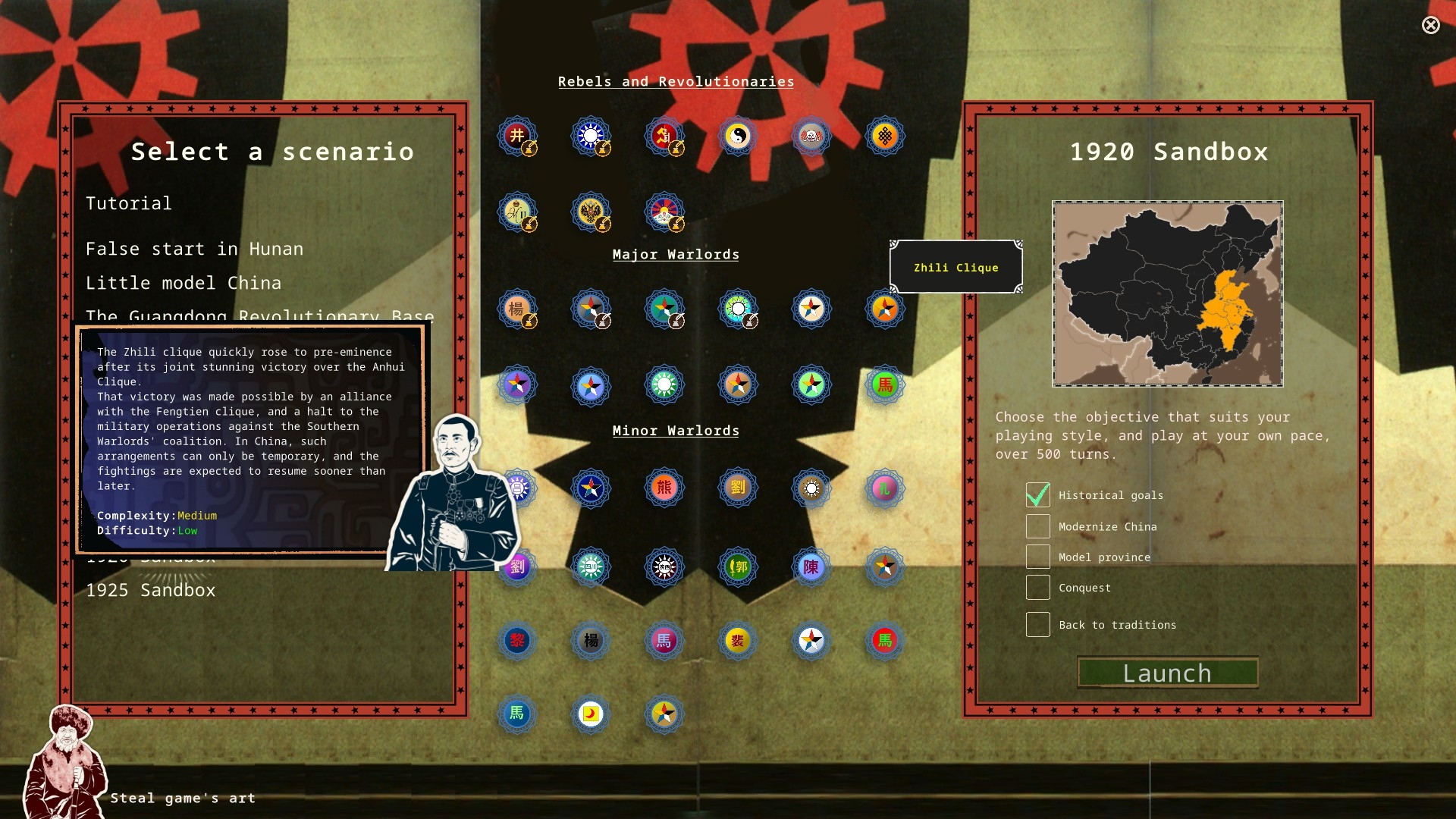

Almost all of the time I’ve spent with RotWS thus far has been spent playing single province scenarios such as Wild Mongolia, Sichuanese Scrum, and False Start in Hunan. Sufficiently short and bijou to be played to completion in a single evening, and firmly rooted in obscure-yet-fascinating history, these outings are primarily military in character. I’ve yet to properly explore the game’s jawdropping 500-turn sandbox scenarios.

Encompassing all of China and playable from over 40 different perspectives (12 major and 21 minor warlords, and 9 rebel/revolutionary groups) these Paradoxesque time-sinks encourage economic, social, and diplomatic meddling as well as violent conquest. Long-term orders such as road building, modernising agriculture, and building relationships with western powers that are a waste of Qi in the brief scenarios would, I suspect, tempt in the country-wide marathons.

Rise of the White Sun’s difficulty settings are its numerous factions. When you choose a side at the start of a scenario, there’s an indication of what its starting position, characters, assets, and allegiances are likely to mean for your victory/survival chances. As in most Paradox titles, although choosing a minnow means you don’t have to manage a dizzying selection of armies and districts from the outset, it can – if you pick the ‘wrong’ tiddler – leave you feeling hamstrung or lead to an extremely short game.

Appropriately, enemy AI in this Warlord Era sim is far from languid. Leave a border district poorly defended in the single-province scenarios, and there’s a good chance a nearby enemy army will lunge for it at the end of your turn. One of the minor flaws of scens such as Wild Mongolia is a routed or spooked force in a peripheral district will cease to exist if it can’t find a viable retreat destination. Having lost a few sizeable armies this way, I feel the game probably needs a mechanism that partially compensates a player on the receiving end of an edge annihilation.

It’s impossible not to admire Maestro Cinetik for taking on a topic as unfashionable and complicated as Warlord Era China. Because of this dinky studio’s pluck and ambition, I’ve spent the past week in the company of a cast of extremely colourful historical figures few of whom I’d encountered before. I’ve not only met memorable geezers such as Roman von Ungern-Sternberg, Ja Lama, and Bogd Khan, I’ve walked (and ridden) miles in their fur-lined boots. While clued-up Sinophiles will doubtless find fault with aspects of Rise of the White Sun’s history abstraction, and tactical wargamers may find the game’s warmongering a tad shallow in places, this £15 orientity entertains and illuminates so spiritedly, any buyer’s remorse should be short-lived.

Thanks for the recommendation. Just fired up the tutorial and I certainly can attest for a great art style and an interesting subject

I’m one of those who found the demo last year to be fascinating and mystifying in equal measures. So glad to hear that it’s a lot more accessible now – I’ll definitely be giving it another shot. Love Maestro Cinetek’s idiosyncratic approach to wargames (CoW: Stalingrad manages to capture desperation so well), and it really is such an interesting subject.