THC’s latest sim-powered rail tour starts and ends in the city of Jeremiah Colman, Alan Partridge, and John Grix. John Grix? At the height of the Norwich Blitz, this plucky fifteen-year-old worked as a Civil Defence messenger. As the bombs rained down, he cycled through streets illuminated by flame and strewn with rubble and glass, delivering messages to emergency workers and offering assistance where he could.

During the April 1942 ‘Baedecker raids’, despite being blown off his bike five times, and burned by acid spewing from a damaged chocolate factory, John refused to quit. The citation that accompanied the British Empire Medal awarded to him later in the year, talks of his “devotion to duty” and “complete disregard of personal safety”. Me and Roman – respectively your tour guide and driver today – think John and his fellow Blitz couriers are long overdue their own video game.

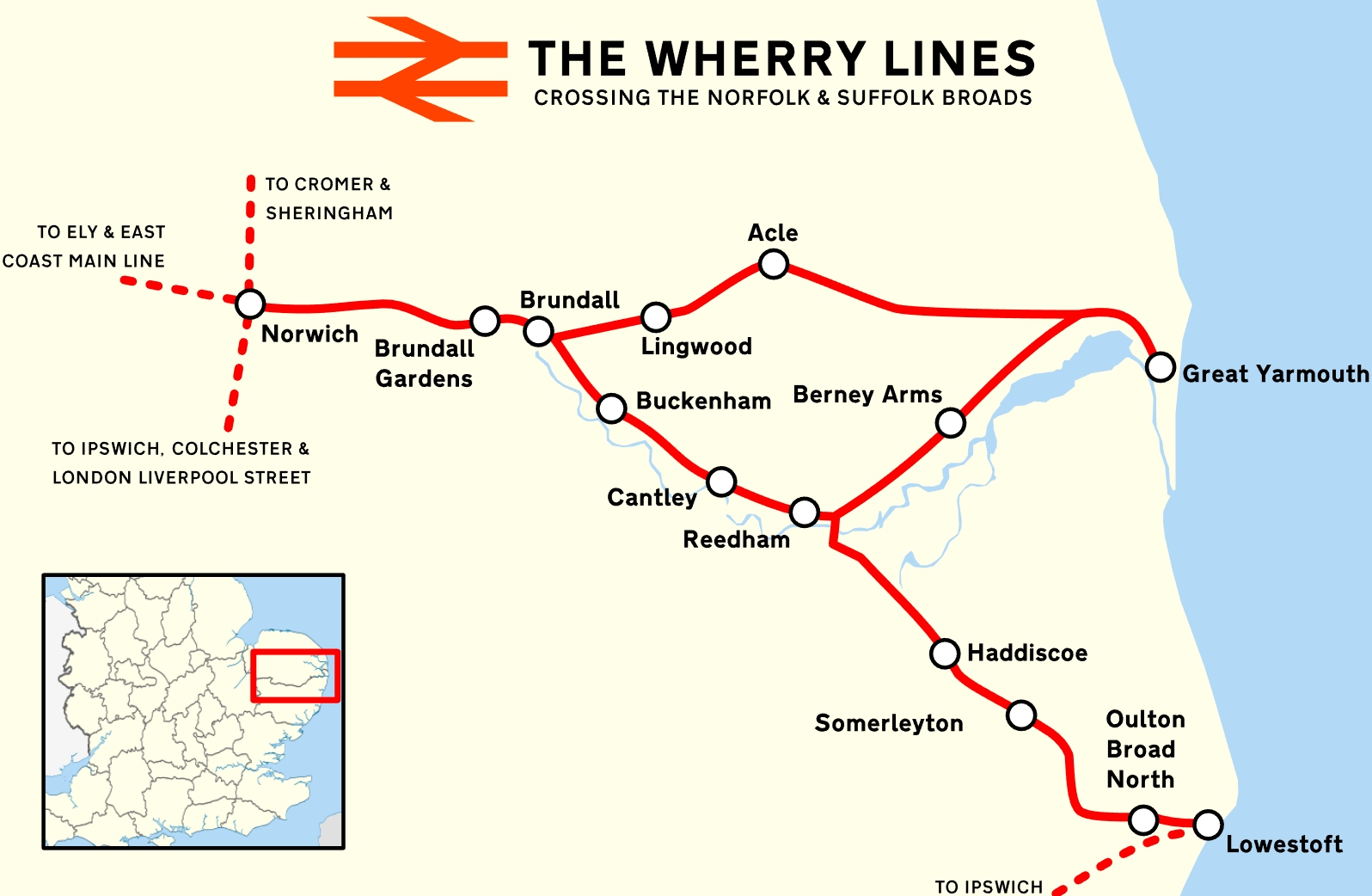

Everyone aboard? On the table in front of you should find a complimentary Terry’s Chocolate Orange (ignore the superficial box damage, the chocolate inside is perfectly edible) and a map showing our route. In Part 1 we’ll travel to Great Yarmouth via Acle, then head south-westward to Berney Arms. In Part 2 we’ll visit Lowestoft, before returning to Norwich via Cantley and Buckenham.

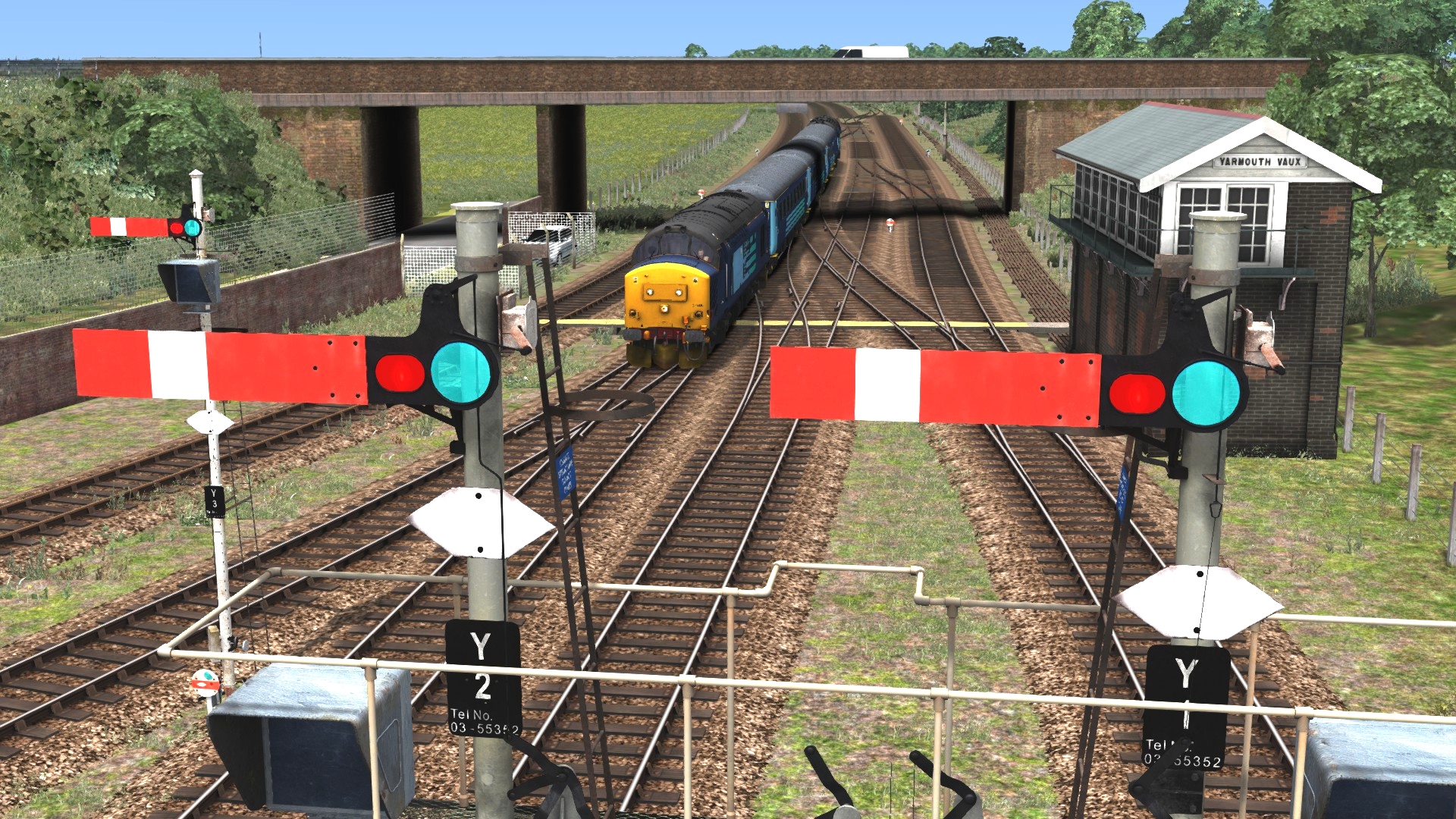

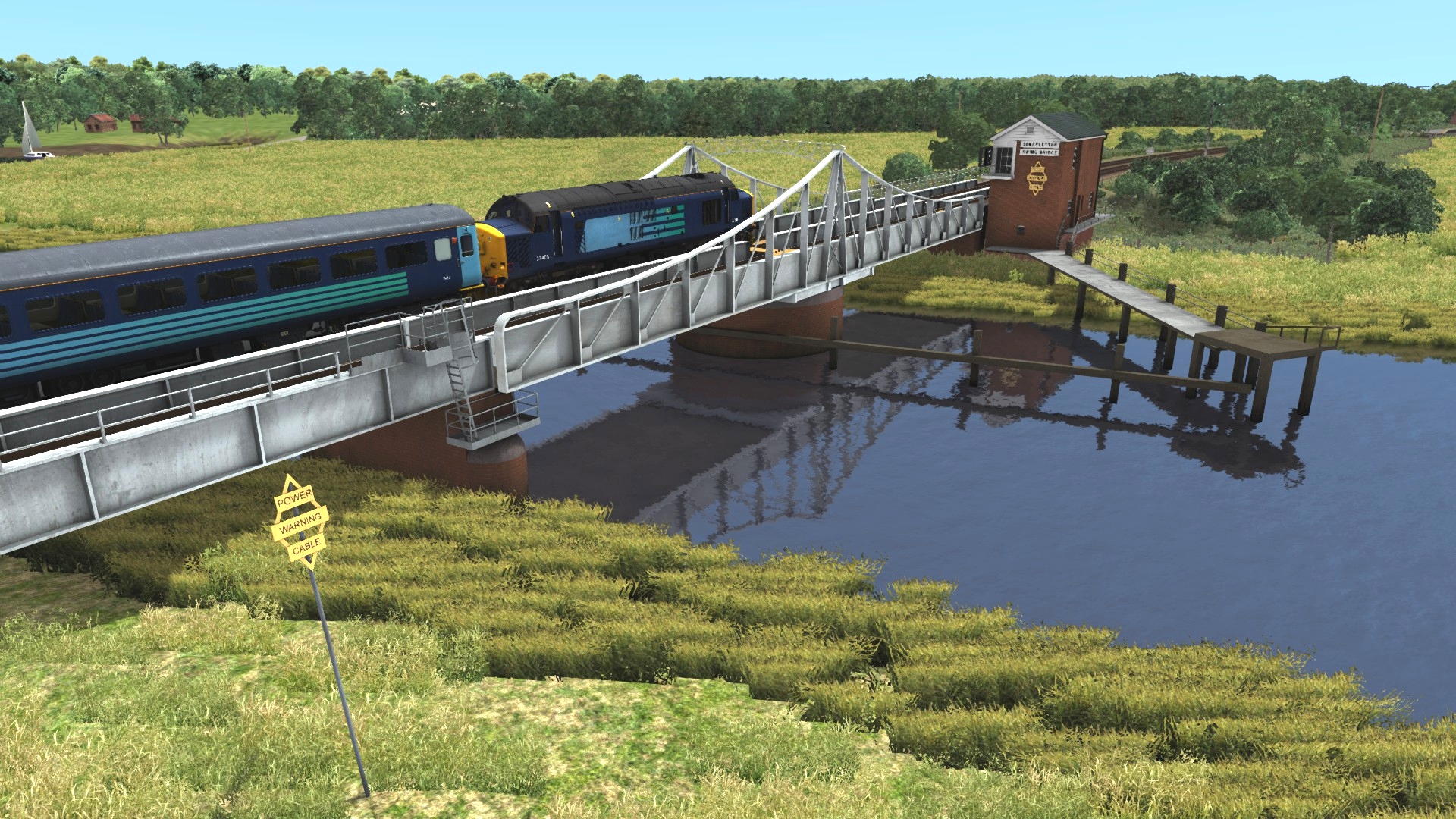

Named after the wind-propelled trading craft that were, at one time, common on the waterways of this decidedly soggy portion of eastern England, the Wherry Lines were, until fairly recently, one of the few parts of the British rail network where diesel locos still hauled passenger trains. While the mellifluous Class 37s were supplanted by charisma-short bi-mode Class 755 multiple units in 2019, and the area lost its lovely semaphore signals around the same time, thanks to Train Sim add-on artisans Armstrong Powerhouse we get to roam the Norfolk and Suffolk Broads’ permanent way prior to modernisation.

That throaty burble you can hear is the sound of two step-fronted 1750 bhp diesel locomotives forgetting that they’re almost old-age pensioners. As we depart the station known as Norwich Thorpe in the days when Norfolk’s county town had three rail termini, if you glance right you’ll see Armstrong Powerhouse’s somewhat crude representation of Carrow Road, the home of Norwich City FC. The strangest sporting fixtures ever hosted at the stadium were probably the two rodeos organised by USAAF personnel from East Anglian B-17 and B-24 bases in the summers of ’43 and ’44. Predictably, competitors from Texas “took the cake” on both occasions.

The catenary overhead won’t be with us for long. Electrification reached Norwich in the mid Eighties and doesn’t extend far beyond Crown Point Train Maintenance Depot, the large structure visible on our right at the moment.

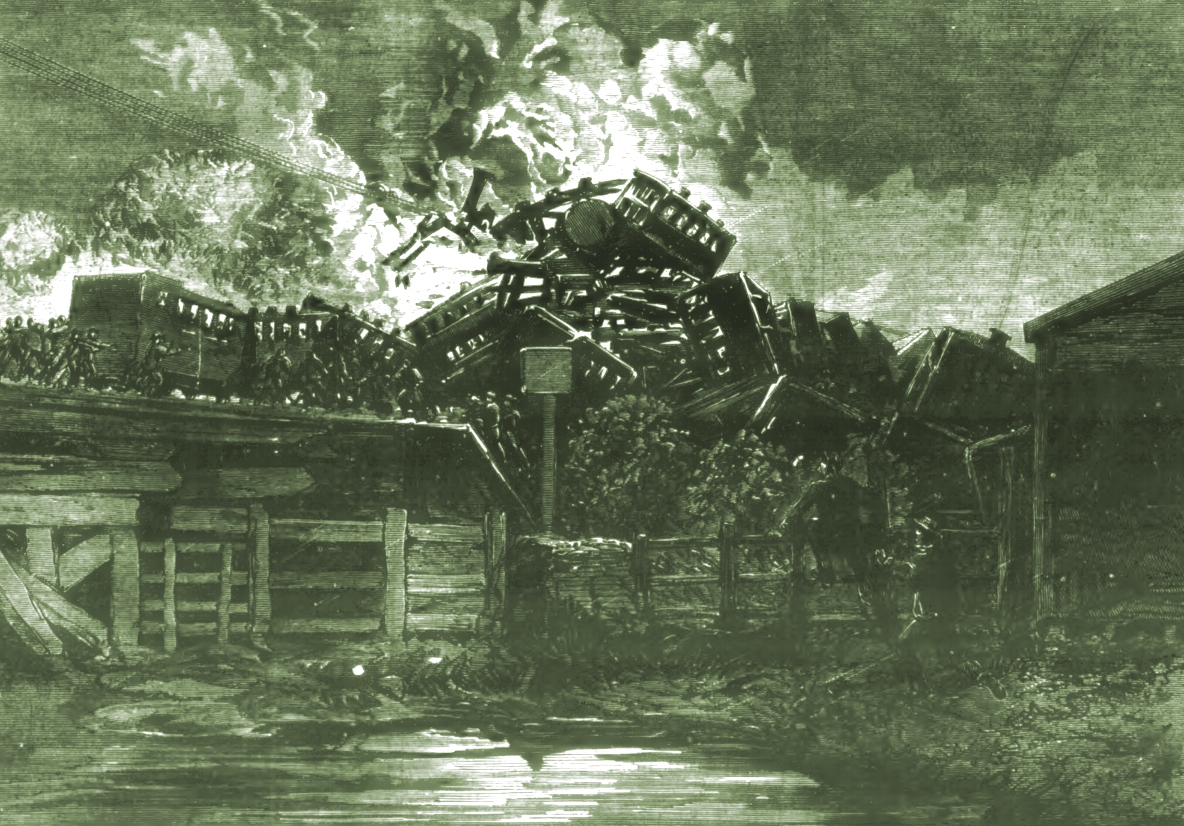

We’re now crossing the Yare, the navigable river that links Norwich to the North Sea. On the night of September 10, 1874, very close to this spot, 25 people lost their lives and 75 were injured when a telegraph clerk’s error led to two lengthy trains colliding head-on. If the accident had occured on this bridge or the trains had been marshalled differently (the up train had a loaded fish van and a guards van directly behind the engine, the down train a horse box) the death toll could have been much higher.

Some good did come from the Thorpe Rail Disaster. Edward Tyer’s Electric Train Tablet system was devised in response to the tragedy, and, remarkably is still preventing collisons on one small section of the British rail network today.

Marinas like the one over yonder are, of course, a vital ingredient in the Broads’ success as a tourist destination. In the first half of the 19th Century, pleasure craft would have been an extremely rare sight hereabouts. The coming of the railways combined with the writings of Broadland enthusiasts such as George Christopher Davies changed all that. Davies’ children’s book ‘The Swan and her Crew’ (1876) and guide book ‘The Handbook to the River and Broads of Norfolk and Suffolk’ (1882) brought many a moneyed Victorian to this area. The ‘Swallows and Amazons’ of its day, the former tome recounts the adventures of three nature-loving boys and their homemade boat. Unsurprisingly, some of Frank, Jimmy, and Dick’s methods would raise the eyebrows of young naturalists today.

Postwick park and ride, the bus-served car park passing on our left, takes its name from the village we’re about to skirt. Postwick’s most famous resident is unquestionably James Adams, one of only a handful of civilian Victoria Cross winners. Rector of Postwick from 1887 to 1894, Adams won his gong for bravery during the Second Anglo-Afghan War…

“During the action at Killa Kazi, on the 11th December, 1879, some men of the 9th Lancers having fallen, with their horses, into a wide and deep “nullah” or ditch, and the enemy being close upon them, the Reverend J. W. Adams rushed into the water (which filled the ditch), dragged the horses from off the men upon whom they were lying, and extricated them, he being at the time under a heavy fire, and up to his waist in water.

At this time the Afghans were pressing on very rapidly, the leading men getting within a few yards of Mr. Adams, who having let go his horse in order to render more effectual assistance, had eventually to escape on foot.”

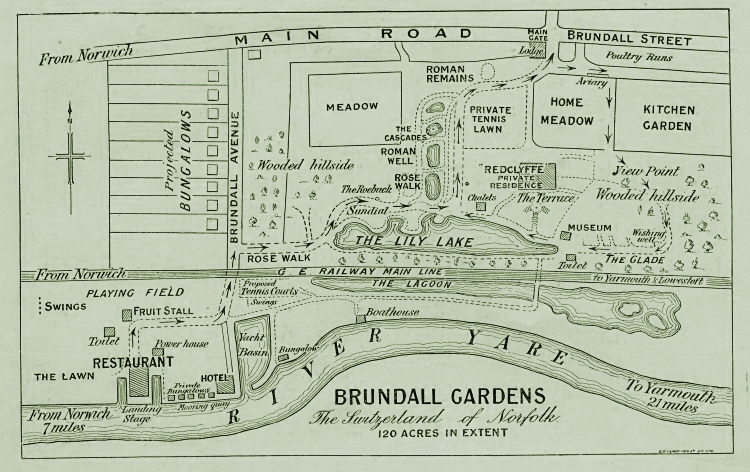

The next station on the line is relatively young by Wherry Lines standards. While this section of Norfolk’s rail network was built in the early 1840s, platforms didn’t appear at Brundall Gardens until 1924. An inter-war tourist attraction marketed somewhat optimistically as “The Switzerland of Norfolk” was the reason for the new station.

The brainchild of East Anglian cinema magnate Frederick Holmes-Cooper, said attraction offered sod-all in the way of spectacular peaks and skiing opportunities, but day-trippers from Norwich and Yarmouth after picturesque surroundings for a picnic, stroll, snog, or murder probably left happy.

After Brundall Gardens comes Brundall and our first glimpse of the Wherry Lines’ splendid mechanical signals. Most of the semaphores on this route were unique in some way, and the diligent devs have worked hard to capture the character of every installation. Impressive multi-signal brackets, white back boards to aid visibility, identification plates, low-level repeaters so drivers don’t have to crane their necks, visible cable runs… if it existed in reality, there’s a good chance Armstrong Powerhouse have simmed it.

We’re about to take the single track Acle line at the 15 mph junction up ahead which means it won’t be long before we are bustling through Lingwood, a station that is, in a signalling sense, highly unusual.

Between 1962 and the recent resignalling, Lingwood was protected by ‘distants’ only. In theory lamps and red discs on the manually controlled crossing gates either side of the station, acted as stop signals.

In 1940 the lyrical Arthur Mee described Acle, the last stop before Yarmouth, as “one of the gates of Windmill Land.” AP can be forgiven for failing to model the bridge he mentions in this evocative passage…

“To every broadsman who quants his wherry along the slow rivers, Acle Bridge is a haven or a port of call, and many are the little ships of adventure which lower their masts and sails to pass beneath. Here summer nights are as gay as a Venetian gala.”

… – it’s more than a mile from the station – but St Edmund’s, the village’s fine thatched church, is much closer to the line and arguably deserved a polygonal nod. Amongst its treasures is a piece of grim Medieval graffiti probably scrawled at the height of the Black Death.

“Oh lamentable death, how many dost thou cast into the pit!

Anon the infants fade away, and of the aged death makes an end.

Now these, now those, thou ravagest, O death on every side;

Those that wear horns or veils, fate spareth not.

Therefore, while in the world the brute beast plague rages hour by hour,

With prayer and with remembrance deplore death’s deadliness.”

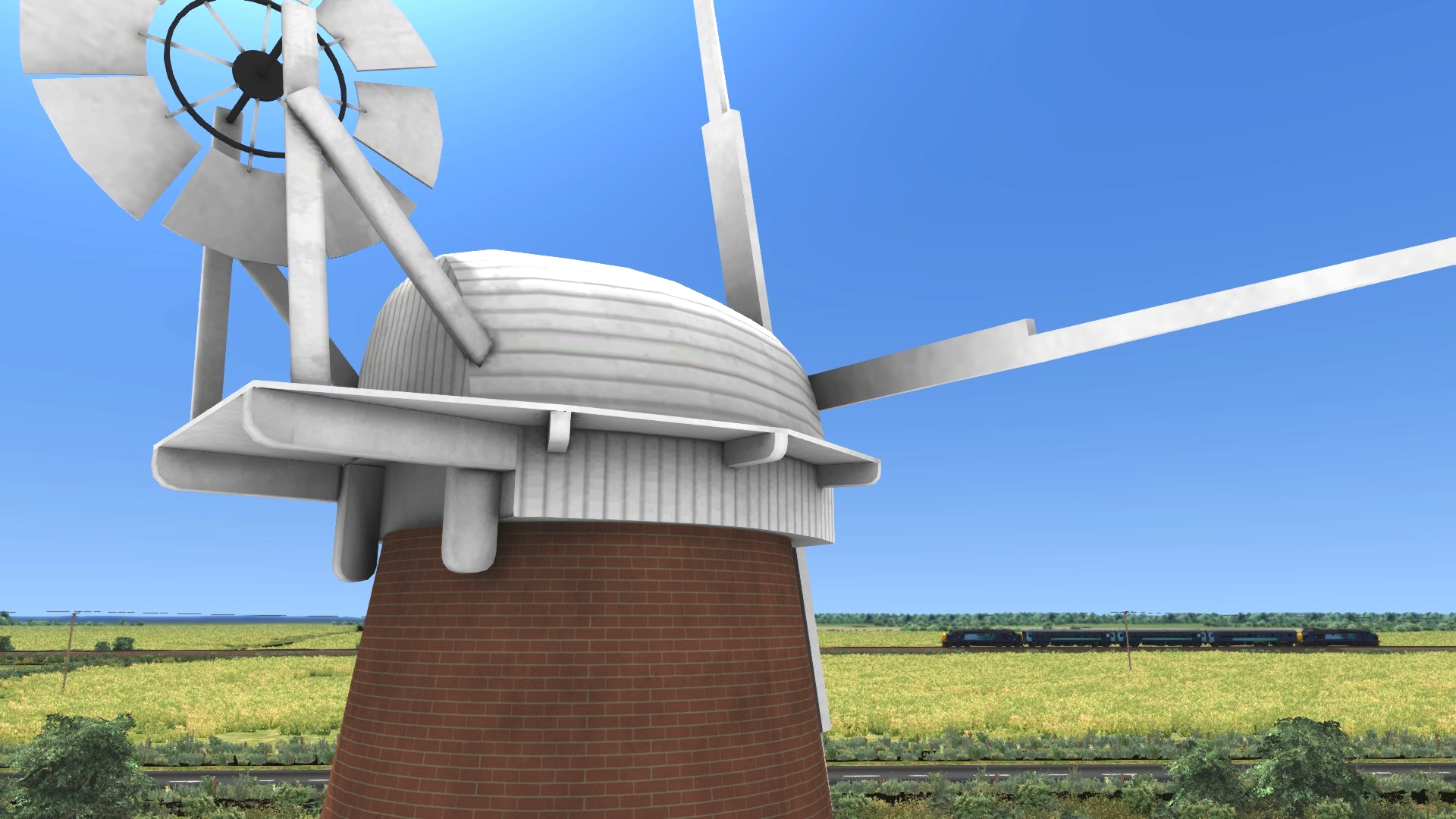

Keep your eyes peeled between here and Yarmouth and you’ll spot around half a dozen ‘windmills’. My air quotes reflect the fact that few of the wind-harnessing structures hereabouts ever milled anything. Their purpose was to pump water from the Halvergate Marshes so that the land could be grazed. All that remains of most of the ‘drainage mills’ that once dotted Norfolk are sail-less brick stumps, but visible on the left currently is an exception – the restored Stracey Arms Windpump. Early in WW2 when invasion fears were rife, Stracey’s stout construction and position overlooking both the railway and the A47 led to it being converted into a multi-storey pillbox.

Wherry Lines is the perfect Train Sim add-on for anyone who loves hearing British diesel locos blurt doleful two-tone warnings. Although only 44 miles in length, it’s a route positively teeming with cross-track footpaths and occupation crossings. As you’ll have no doubt gathered by now, the straight stretch we’re currently barrelling along, is particularly rich in air horn opportunities.

The line converging from the right and the weed-infested carriage sidings on the left mean we’ll soon be drawing into Great Yarmouth’s only remaining station.

For centuries, this coastal town owed its prosperity to the humble herring. When the industry reached its peak in the years leading up to WWI, the local harbour was home to over 1000 ‘drifters’. By 2008, over-fishing, changing tastes, and foreign competition had reduced Yarmouth’s fishing fleet to just one vessel.

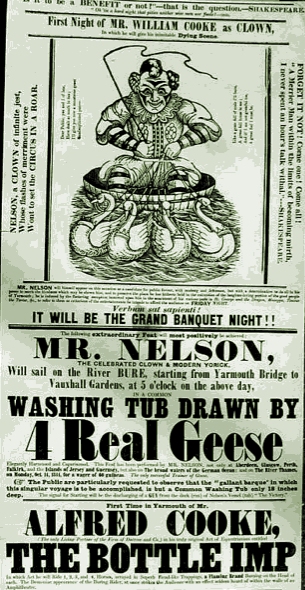

Devising a horror movie or novel set in contemporary Yarmouth would be easy. The supernatural fright fount would have to be Arthur Nelson, the Victorian circus clown. On May 2nd, 1845 Arthur was drumming up business for Cooke’s Royal Circus by sailing through the town in “a washing tub drawn by 4 real geese”*. The stunt was watched by thousands, several hundred of whom took to the town’s relatively new suspension bridge for a better view. 79 of the people hurled into the murky River Bure when the bridge failed, perished. 59 of the unfortunates were children.

* The tub was actually connected to a rowing boat by a hidden line.

While in Yarmouth I’d also planned to tell the story of a WW2 bombing raid that took the lives of 26 ATS girls, but judging by your downcast expressions, perhaps I’ve dispensed enough doom and gloom today. Let’s move on.

One of the advantages of ‘top and tail’ working is Roman and I don’t need to faff about with grimy couplings and points levers before departing for Lowestoft. Once my colleague has walked down to the other end of the train, we can be on our way.

That lake on the left is Breydon Water, the UK’s largest protected wetland. Every autumn, when the hotels and B&Bs, and the promenades and piers of Great Yarmouth begin to empty, the mudflats, reedbeds, and lagoons around here start filling up with tens of thousands of feathered holidaymakers. Wigeons, Bewick’s swans, golden plovers… most of the visitors hail from North-Western Europe. Once in a while, however, travellers from much further afield pause at Breydon.

Hear that change in track rhythm tempo? We’re slowing for Berney Arms, one of the least used and most remote stations on the British rail network.

Lucky to see 400 passengers a year, the majority of the people who alight at this desolate request stop today are either ramblers, bird watchers, or windmill enthusiasts.

A few minutes walk away to the SE is a well-preserved tower mill built in 1865 to grind not corn but a mix of kiln-burnt chalk and river mud. Before conversion to a windpump in 1880, the lofty Berney Arms Windmill produced cement.

TO BE CONTINUED

(Tune in next week for tales involving, amongst other things, crashed Flying Fortresses, ground-breaking vehicles, and splendid swing bridges)

I’m pretty sure I’ll never play a train sim, but I love reading these well written travel reports, in places where is little chance I’ll ever go. Thank you Tim!

Admitting to be somewhat of a railway philistine, I do wonder what exactly those two ?gangways? running along the obviously unused part of the tracks (visible in picture broadland14.jpg) are for. Inspecting the rails for damage? Evacuation of passangers in case of an engine breaking down? Signifying the way to the Switzerland of Norfolk?

See https://www.google.com/maps/@52.6184515,1.7139536,117m/data=!3m1!1e3

I’m not sure, but I’m guessing they’re to enable people to enter/exit/inspect trains sat in the sidings from platform height.

I normally sigh sadly when I spy a pixel loco on THC’s masthead and look away, as I too am unmoved by trains (much like Greater Anglia’s passengers often). Today however I read on interestedly as I hail from, and indeed still live in, the Fine City. Thank you Tim!

Which game was this done in?

The Dovetail sim now known as Train Simulator Classic…

https://store.steampowered.com/app/24010/Train_Simulator_Classic/

…enhanced with Armstrong Powerhouse’s ‘Wherry Lines’ route:

https://store.steampowered.com/app/376970/Train_Simulator_Wherry_Lines_Norwich__Great_Yarmouth__Lowestoft_Route_AddOn/

Thanks Tim!