If the EU’s habit of co-funding vapourware doesn’t bother you, then I suspect you won’t be overly concerned by the fact that their grant granters, Creative Europe, openly discriminate against many of the Continent’s most talented, successful, and commercially minded developers.

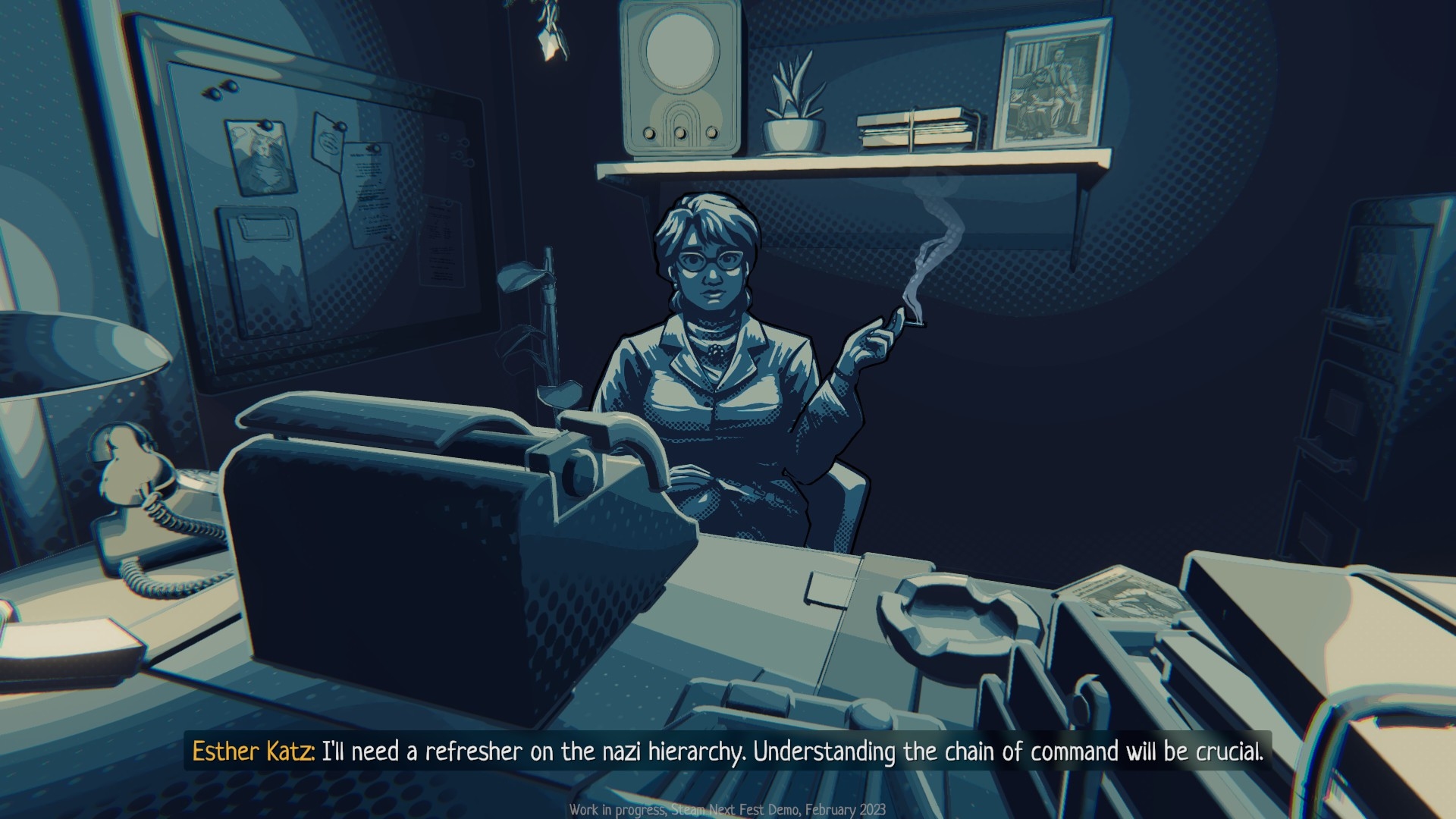

If any of the studios behind the following games had tried to get financial support for them from CE, they’d have come away empty handed…

Although Creative Europe claims to be working to “increase the capacity of European video game producers, to develop video games and interactive immersive experiences with the potential to reach global audiences” and “improve the competitiveness of the European video games industry”, its bizarre prejudices, and the odd way in which it assesses projects, means it actually ends up doing something quite different.

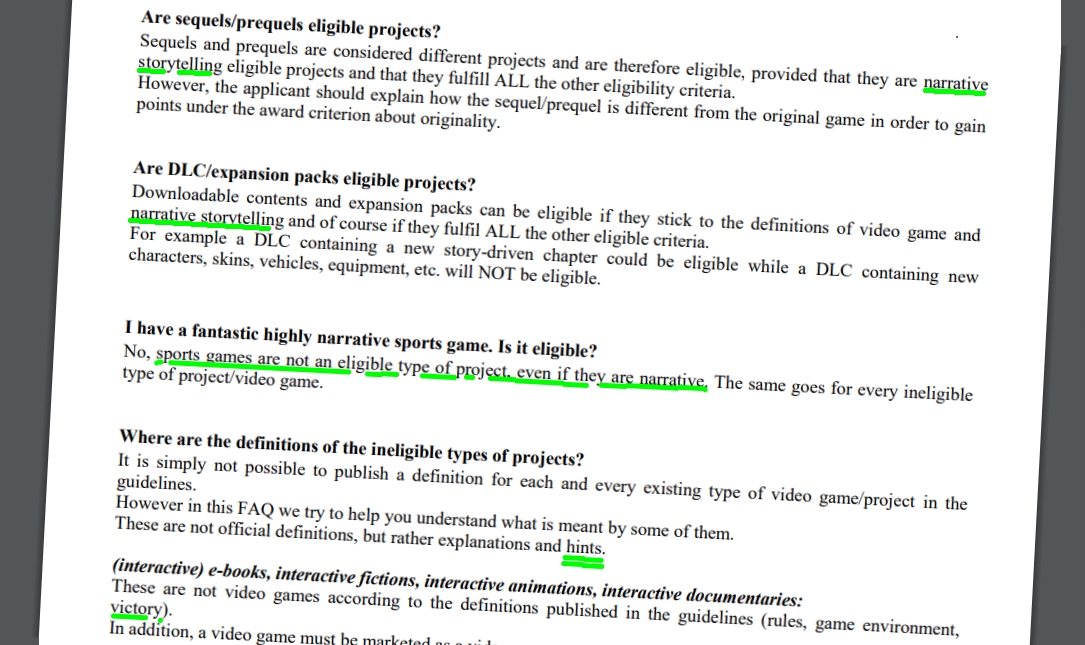

Since its involvement with gaming began over a decade ago, Creative Europe has only ever awarded grants (up to 150k Euro per title in the past, up to 200k going forward) to projects with “substantial narrative elements”.

Why? While I can’t find an official statement explaining the policy, and, thus far, have been unable to wring an explanation from an employee, I suspect this fetish for story stems from the fact that the people who laid the foundations of the programme were movie buffs seconded from the organisation’s well-established cinema department. Seeking comfort in the familiar, and fearful of things they didn’t fully understand (arcade games, sandboxes, emergent gameplay, virtual violence…) they slapped a big fat “MUST CONTAIN NARRATIVE!” clause into their selection criteria then sat back, waiting for the worthy/arty quasi-movie pitches to roll in.

Inexplicably, CE’s belief that the only worthwhile or culturally significant games are narrative-driven games, hasn’t softened as time has passed – it seems to have grown more entrenched. While the aid givers have always rejected applications from studios that can’t demonstrate “a proven track record” in producing games with a “substantial narrative element” (It’s not enough that the project under consideration is story-wreathed, one of its predecessors must be too!) now they are keen to emphasise that a project’s story “must be told throughout and not only as an introduction or ending”. Evidently, some crafty charlatans have been trying to get their hands on EU funds by embellishing narrativeless entertainments with token touches of tale. How disgraceful!

Interestingly, one developer happy to talk to me about grants, wasn’t all that fussed about the yarn stipulation that effectively prevented him from getting help from the EU. A successful sim-smith, he noted noted that the current rules “might actually be favourable to me. I’d hate to see new publicly funded competitors popping up 🙂”.

This unexpected comment got me thinking about the unintended consequences of the current system. Ironically, by bestowing their favours on storytelling studios only, CE must be making things harder for one-person-bands operating in storyville. Lone wolves too busy to tackle a convoluted grant application and – if they don’t speak English (the preferred language for submissions) – too poor to hire a translator, find themselves on a playing field tilted unhelpfully by CE’s well-meaning interventions.

Even if Creative Europe eventually realise that the makers of titles such as New Heights and HROT are just as deserving of assistance as the makers of diversions like The Darkest Files and The Wreck, and ditch mandatory narratives, its grant system will remain vulnerable to accusations of unfairness. An intimidating application procedure and a project assessment system that feels like it has been pinched from an obscure Nineties games mag, guarantee that.

Published lists like this one suggest that perhaps thirty percent of the projects submitted to CE are thrown out before reaching the scoring stage. Thus far I’ve not managed to talk to a studio that has fallen at the first hurdle or given up prior to reaching it, but hopefully I can find one before putting together next Friday’s article (In Part 3 I intend to share the thoughts of industry insiders, and wrap things up with a few constructive suggestions).

At least one of the individuals you’ll hear from next week isn’t wholly convinced CE’s pivotal scoring system is up to snuff. To have any chance of securing a hand-out from the lads and lasses in Bruxelles, a proposal must score at least seventy on this bewildering rubric:

RELEVANCE (35 points available)

a) Originality and creativity of the concept against existing work, including originality of the story (10 points)

b) Level of innovation: “cutting edge” technique and content, such as use of new or latest technologies or platforms, innovation in gameplay, level of immersion and interactivity, innovation in visual/graphic approach, innovative use of cinematography and viewing (15 points)

c) Adequacy of the strategies presented to ensure a more sustainable and environmentally-respectful industry (5 points)

d) Adequacy of the strategies to ensure gender balance, inclusion, diversity and representativeness, either in the project/content or in the way of managing the activity (5 points)

QUALITY OF CONTENT (25 points available)

a) Quality of storytelling

b) Quality of visual approach (e.g. artwork, mock-ups, sketches, mood boards)

c) Quality of the graphic and sound design

d) Accessibility measures for users with disabilities and other impairments

e) For non-immersive video games:

– Quality and originality of the gameplay

– Integration between gameplay and storytelling

– Quality of the level and character design

f) For interactive immersive video games and experiences:

– Quality of the immersive experience

– Level and quality of interactivity

PROJECT MANAGEMENT (20 points available)

a) Adequacy of the development strategy (10 points)

b) Adequacy of the financing strategy and feasibility potential of the project (10 points)

DISSEMINATION (20 points available)

a) Potential for European/international exploitation and distribution (10 points)

b) The marketing strategy allowing to reach audiences at an early stage (10 points)

I realise you can’t dish out 200K Euro grants on gut instinct alone, but, blimey, is it any wonder the Creative Europe logo rarely appears on the splash screens of smash hits when projects are selected using this absolute dog’s dinner.

What the heck is “a non-immersive video game” and why is Creative Europe tacitly encouraging them? Does the fact that points are awarded for “innovative use of cinematography and viewing” mean the assessors prefer 3D games to 2D ones? If I base my game on a Greek myth or a classic European novel, will that mean my pitch scores poorly for “originality of the story”? Would I be wise to include a non-binary character in my game about life in the Warsaw Ghetto? Should I mention in my proposal that my studio only buys compostable teabags and bog roll made from bamboo? The poor souls manning CE’s national helpdesks must get some interesting questions.

By opting to assess game ideas rather than game prototypes or demos, CE has made life awfully hard for itself. Heaven knows how the evaluators are expected to score things like “quality of the immersive experience”, “quality of the sound design”, and “level and quality of the interactivity” when all they have to go on is text descriptions, concept art, and mocked-up screenshots.

One of the emails I received this week, suggests project scores sometimes baffle grant seekers. The dev in question wished to remain anonymous, but said “I could give you a lot of examples of great projects that never received funding, and on the other hand, projects that should have never received it.”. They went on to describe a situation in which a particular studio submitted two proposals during a call, only to see the one that was “clearly better from a cultural and gameplay innovation aspect” fail while the other succeeded.

As a result of a perverse assessment, has Creative Europe ever found itself embroiled in a court case like this one? Not that I know of, but that might be more down to luck and the understandable unwillingness of devs to bite the hand that feeds them, than anything else.

(To be continued)

*** Postscript ***

So far, only one of the developers mentioned in Ghost Games has responded to my requests for information. Aesir wrote back to say Cavalry – Through The Ages was “cancelled years ago” and that the 150,000 € awarded to the project was never claimed. I have no reason to doubt this statement (this entry from the company’s accounts seems to confirm it). Clearly, just because a project appears in a published awards list, and is listed on CE’s website as ‘completed’ doesn’t mean that the relevant grant was actually delivered/spent. Confusingly, Quarantine – another unreleased, grant-winning Aesir game – is also listed as ‘completed’ on Creative Europe’s site, and does appear to have benefited from EU co-funding.

Doing what the private sector does routinely, funding, and managing to do it poorly. Give me Kickstarter funding any day.

On the contrary, this is a government funded program. Speaking VERY generally, government grant funding for the arts and sciences — at least in the US — is pretty effective (if not efficient) in the context of its impact on major cultural/scientific achievements.

And that’s how I interpret the main thrust of Tim’s argument: giving artists money to make art is a patronage tale as old as time. How could the EU cock up such a well-meaning program so terribly?

I must admit I find Creative Europe’s grant criteria here pretty bizarre, for all the reasons laid out.

Tim — do you know how the applications are adjudicated? I assume there is no peer review to any extent?

Apparently, an “evaluation committee (assisted by independent outside experts)” assess/score all applications:

https://tallyhocorner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/eu28.jpg

I wonder who the members of the evaluation committee and the independent experts are and what qualifications they have. Are they from the gaming industry, gaming journalists or just some sort of cultural functionaries?

It’d be interesting to do a comparison between the results of Creative Europe funding and that of a private company, such as the Epic Games Megagrants (https://www.unrealengine.com/en-US/megagrants), which involve similar sums. I suspect one of the most immediate differences is that it’ll be easier to get the Creative Europe data.

The Creative Europe guidelines strongly suggest that they were written by people with more experience of funding applications than of computer games.

No one asked, but the monoplane pictured above is a Morane-Saulnier ‘Bullet’ in RFC livery. Apparently soon to debut in a forthcoming DLC for Wings Over Flanders Fields

You say that but most of the other screenshots have informative names; the first half-dozen are: a, c, d, b, ee & g.

I’d have thought the third one (labelled d) was Unity of Command 2. (Devs are croatian, I believe, joined the EU in 2013)

Looks worse for the EU this week than last, and the open questions remain:

Do you have to demonstate using this money to accomplish work? If not, why not?

There is a milestone system so, in theory, yes. The milestones don’t look all that demanding/meaningful though…

“During the implementation of the project, the following deliverables must, as a minimum, be provided:

− WP 1 – Updated creative development (treatment, script, bible, game design document)

− WP 1 and/or 2 – Update on key crew/casting

− WP 2 – Link to prototype / trial version / trailer / teaser if produced

− WP 3 – Updated financing/budget and production schedules

− WP 3 – Updated distribution and marketing strategies”

I guess that means that for Tally-Ho Studios sàrl to claim some dosh they’ll have to demonstate the narrative content of their previous game, TotallyNotAFakeGame 2: European Blastinator – Three Hundred and Thirty Five Years’ War

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Three_Hundred_and_Thirty_Five_Years%27_War

I remember European Blastinator very fondly. Although the decision to make the game run in 1:1 real-time, based off the system clock, was definitely an interesting design choice.

European Blastinator was too immersive for me. I prefer non-immersive games like Hearts of Iron.

It may be just me, but I wish the games connected to each screenshot were identified. If they were, I didn’t catch it.

Our host nearly always bestows sensible filenames on THC images so I don’t usually miss captions here, but I was very intrigued by the aircraft one so I assigned myself a nano-Foxer and dug up its origin. The full list of games + devs:

1 – Derail Valley (Altfuture, Serbia)

2 – Farming Simulator 22 (GIANTS Software, Switzerland/Germany/Czech Republic)

3 – Unity Of Command II (2×2 Games and Croteam, Croatia) (as per Col. K)

4 – Euro Truck Simulator 2 (SCS Software, Czech Republic)

5 – Wings Over Flanders Fields (OBD Software, team dispersed but seems EU-based)

6 – Rush Rally 3 (Brownmonster Games, UK)

It turned to be more of a non-Foxer, though, as 1 through 5 were easily ID’d by image search since they’re official screenshots, while game 6 was found to be conveniently labeled once I zoomed in enough.

Equal parts enraging and illuminating – thanks Tim. I think you and other commenters here have hit the nail on the head: this is a decent idea (or a cynical move designed purely for a good-looking slogan/soundbite, but given it’s the EU, I’m guessing it’s the former), crippled by the kind of bureaucracy and middle management that all of our governments seem to be infested with these days. And by middle management, I mean the kind who have almost zero experience with the subject matter of the grant they’re giving out. Their only function, really, is to introduce enough hoops and paperwork to justify their own jobs, a kind of budget-draining cycle of onanistic reinforcement (I wonder how much it costs the EU to administer such a fund?)

Over the past few years I have developed a strange fixation with Scottish politics – strange because I am neither Scottish nor have ever been to Scotland – through the journalism of the very excellent Stuart Campbell, Craig Murray, and Robin McAlpine. Robin in particular often decries this exact kind of “grants run by clueless managerial types”, (one example amongst many: https://robinmcalpine.org/we-must-fight-back-against-stupid-paperwork/) and has really opened my eyes to the parallels everywhere, including right here.

Now, the Creative Europe fund might be well meaning, but I am in complete agreement that it’s probably doing more harm than good, and at best is completely ineffectual. The real effective way about these things, Robin argues, is to just give people the money without all the faff and hoops and “structure in full, local accountability for what they do with it.” Don’t make them dance for a pittance: treat them like adults and give them freedom and as they are the ones with the knowledge and creativity, not the bureaucrats, nine times out of ten they’ll put it to good use.

>>I wonder how much it costs the EU to administer such a fund?

I’ve approached Creative Europe through one of their cultural attaches, and one of the questions I asked was about administration costs. Sadly, no response yet.