THC is lucky enough to have an ex-KCL Wargame Studies lecturer amongst its guest contributors. Today, Arrigo Velicogna assesses Bastogne, a snow-mantled solitaire board wargame that shuns hexagons and deifies dice.

Back in 2017 World at War magazine featured a solitaire game titled Bastogne. In the game you took the role of General McAuliffe and attempted to hold Bastogne against encircling German forces. While I was tempted at the time, budgetary issues prevented a purchase. Recently, with the eightieth anniversary of the Battle of the Bulge coming, I decided to take the plunge, and ended up having a blast.

Designed by Joe Miranda, one of the deans of our hobby, Bastogne has its origins in the States of Siege titles pioneered by Victory Point Games years before the company was acquired by a boardgame giant and disappeared into the void. States of Siege games are predicated on having different tracks along which system-controlled forces advance toward a common centre. If they get to the centre it’s game over. Eons ago I had a very negative brush with the system courtesy of Soviet Dawn, a game I considered awful. That disagreeable experience left me wary of the entire series.

But there is a difference between an up-and-coming game designer like the person behind Soviet Dawn, and an icon of the hobby such as Joe Miranda. The difference is one has the ability to use a flawed system as an armature for building something better.

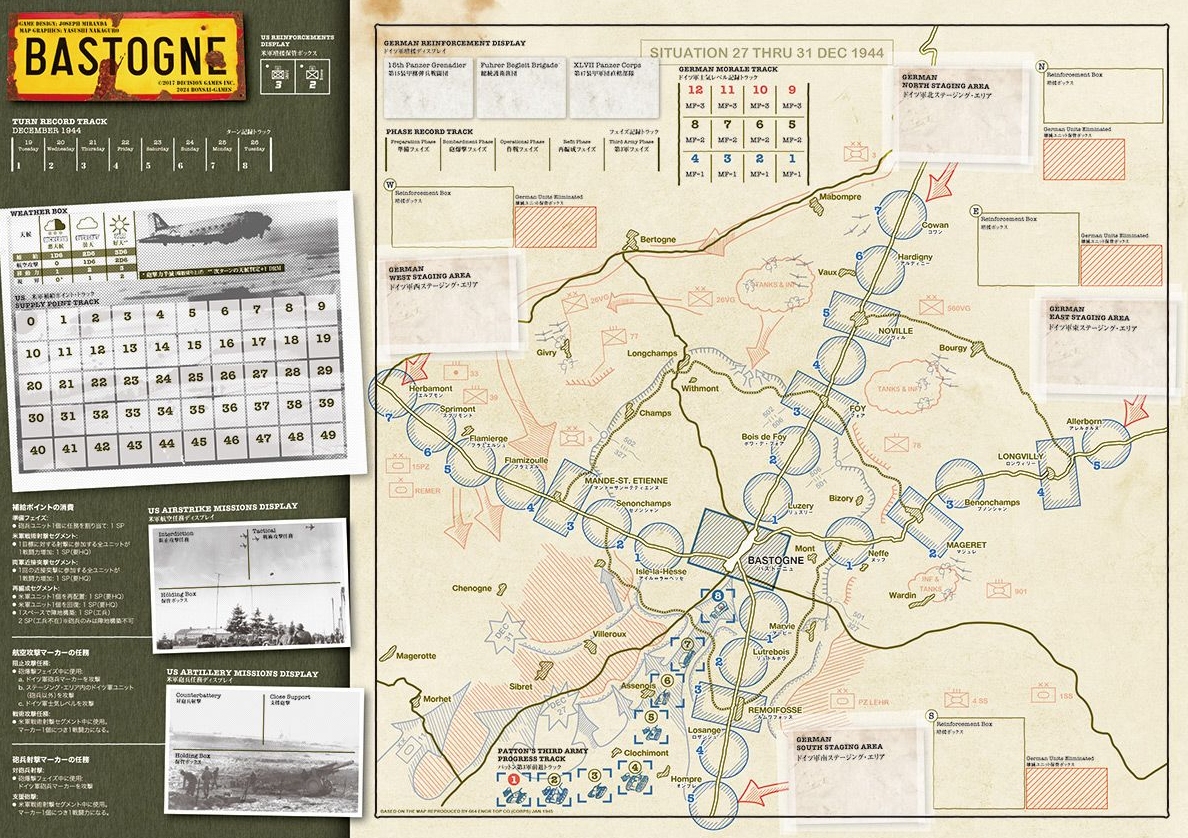

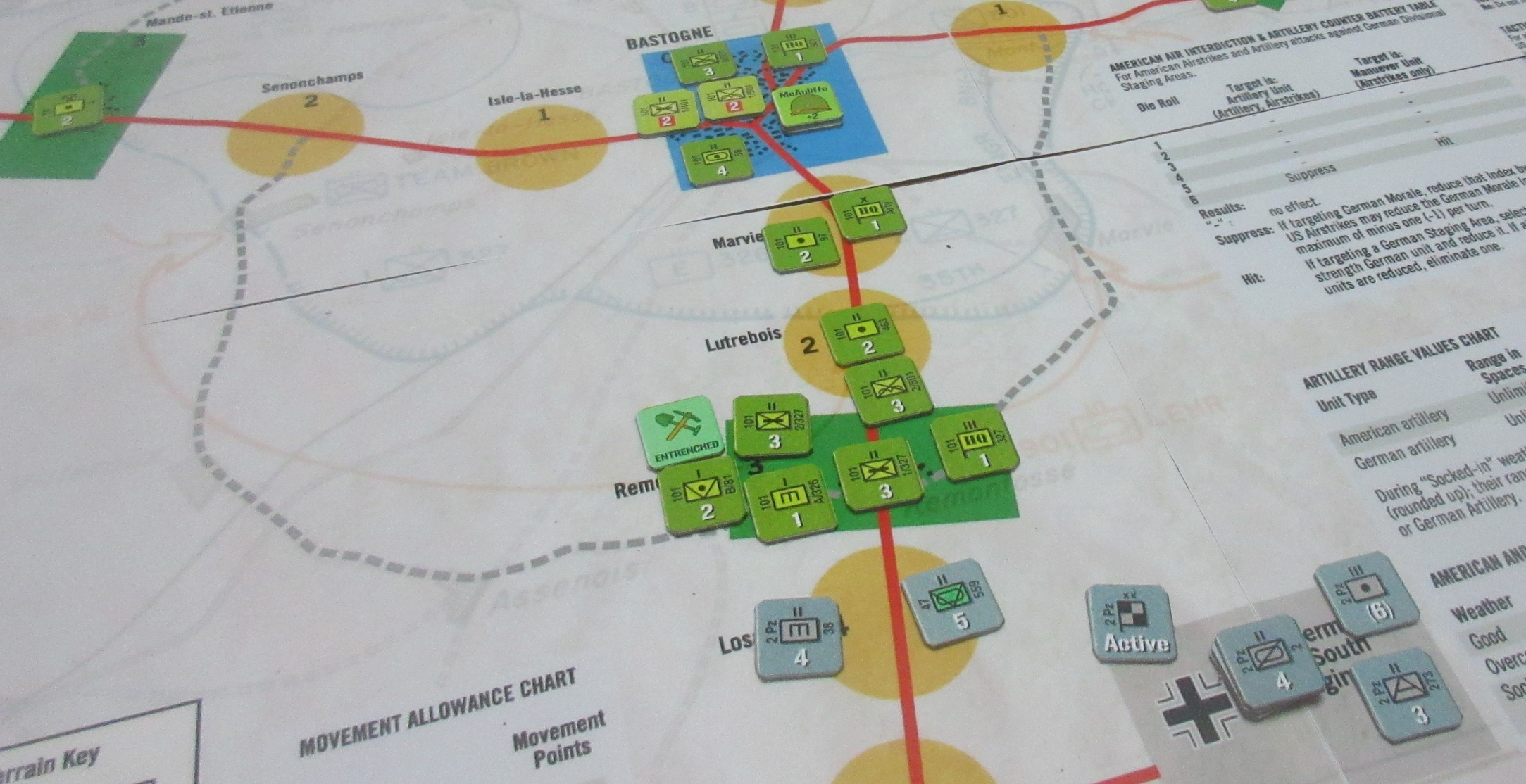

In Bastogne the generic forces are gone, as are the cards controlling almost everything. Instead, we get a quite detailed order of battle largely at the battalion level, rules that ensure German forces surrounding the city exhibit plausible behaviour, and effective shorthand for the constraints both sides had to face (mainly weather and supplies). The game covers the critical period of the siege – December 19th to December 26th – each game turn representing a day of real time. Victory is simple. The Germans automatically win if they control Bastogne. You automatically win if either German morale collapses or Patton’s tanks arrive and relieve the city. If none of this happens by the end of December 26th, you’ve lost.

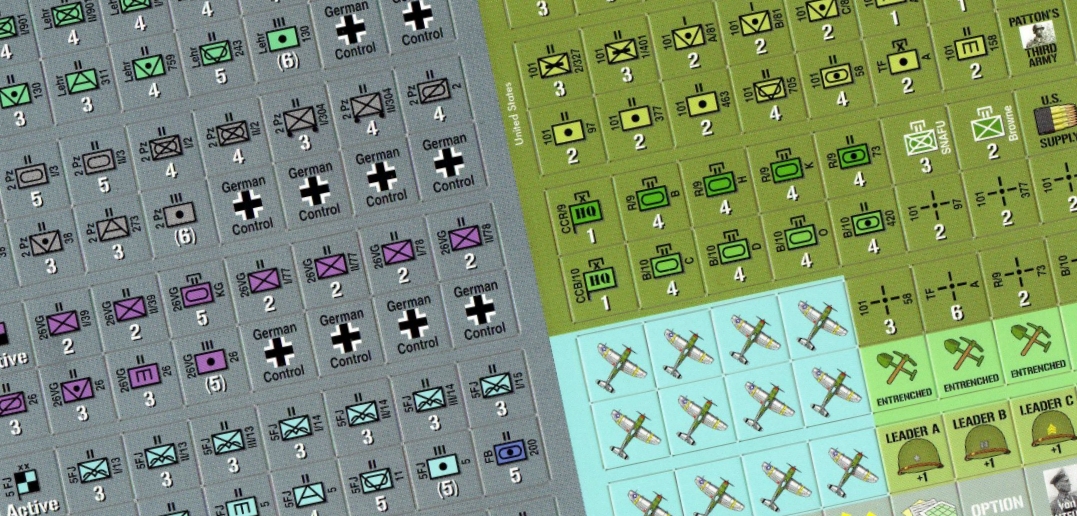

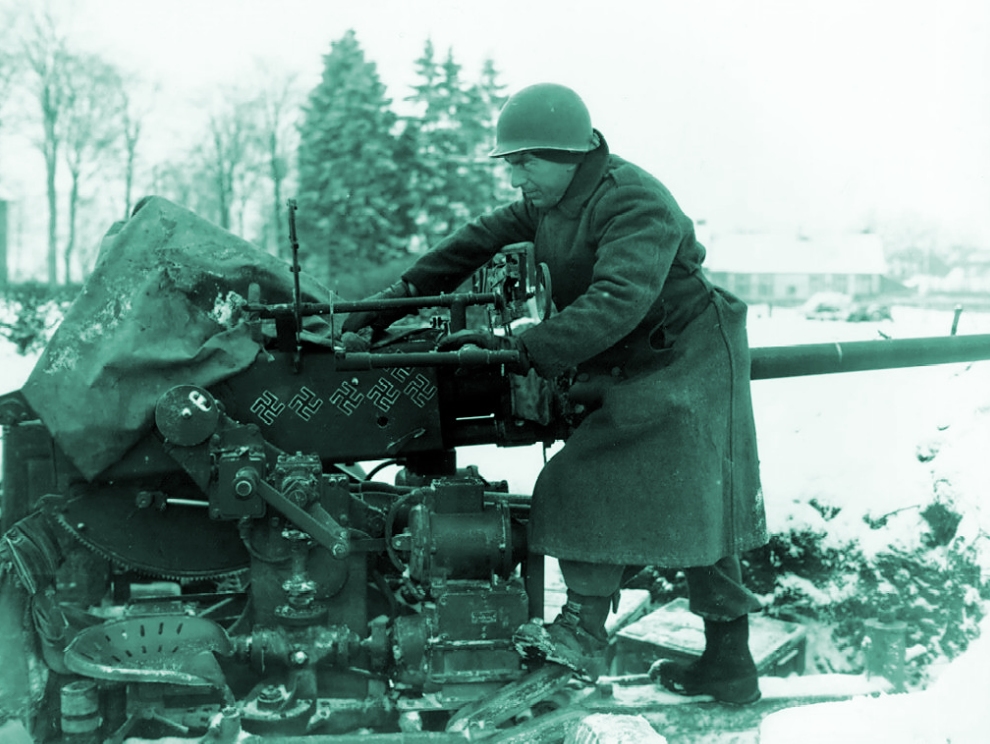

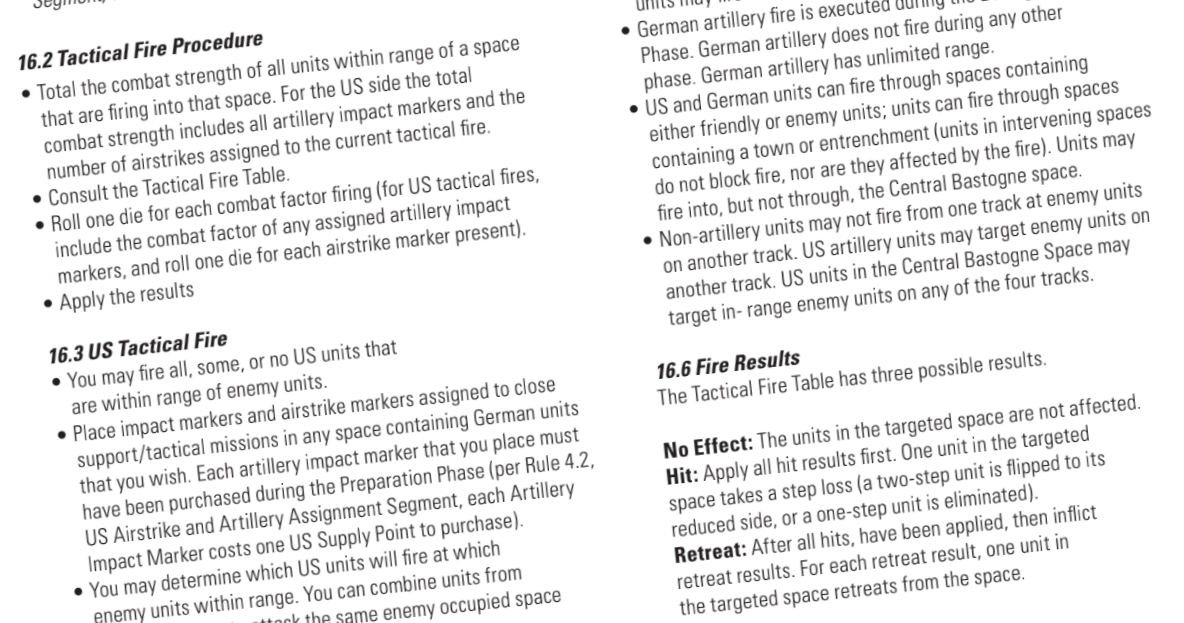

There is only one scenario, but the scenario includes variable elements assuring its replayability. American forces include the 101st Airborne Division, with its four regiments (three parachute infantry, and one glider infantry), two combat commands, one from the 9th and one from the 10th Armored Divisions, and assorted artillery, antitank, tank destroyer and engineer units. The Germans have four divisions at the start, 2nd Panzer and Panzer Lehr, 5th Fallschirmjäger, and 26th Volksgrenadier, supported by corps troops. The 15th Panzer Grenadier Division, and the Führer-Begleit-Brigade, may or may not appear as reinforcements. Units are rated for combat strength (the number of dice they can roll in combat). Battalions have two steps, the smattering of companies only one. Movement allowance is not shown on the counters but depends on the weather for the player (US) and on overall morale for the Germans.

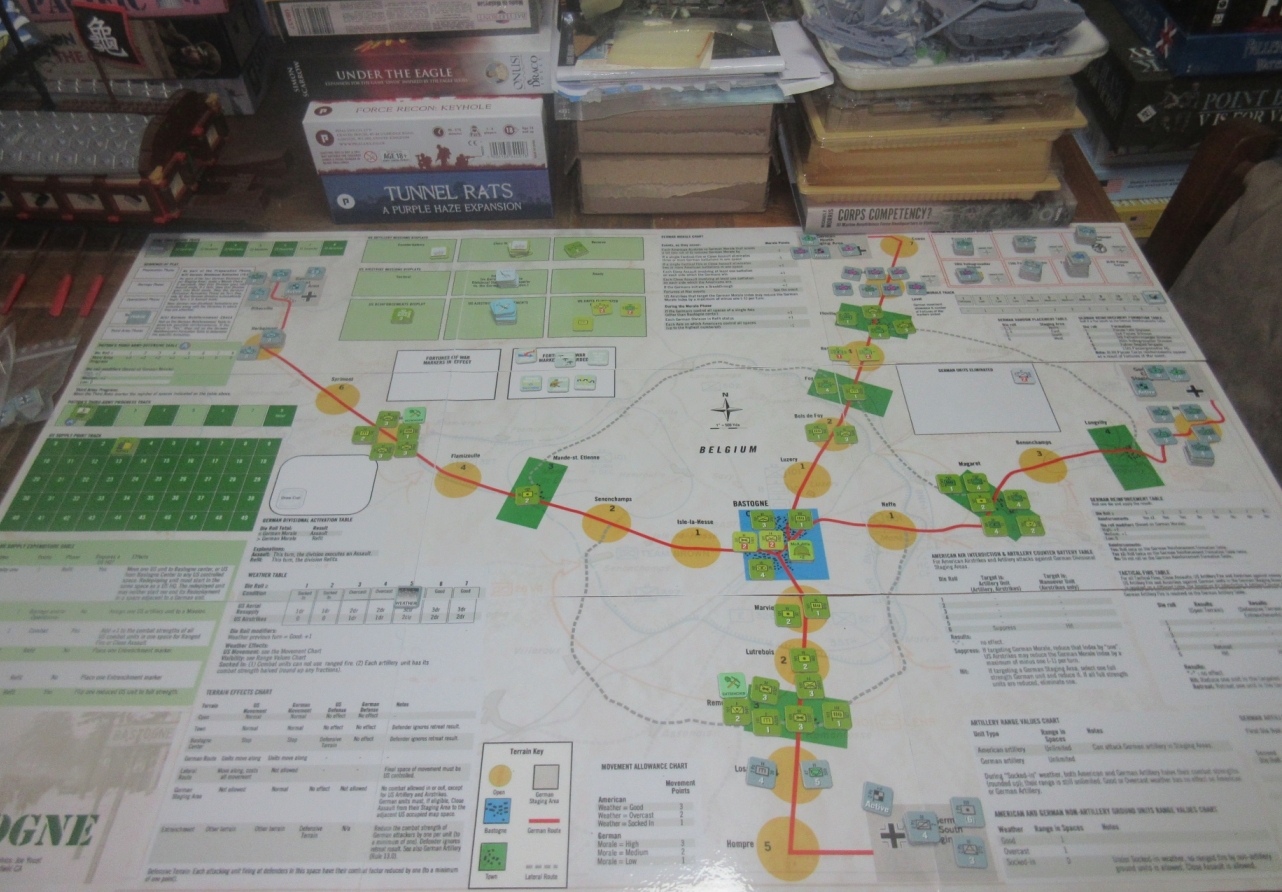

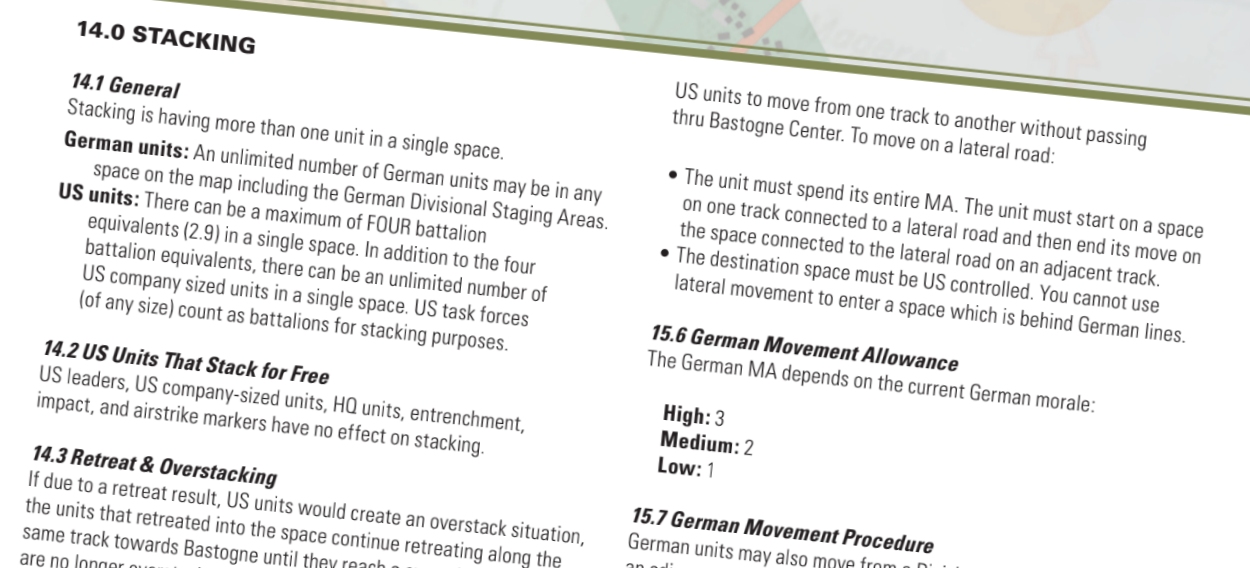

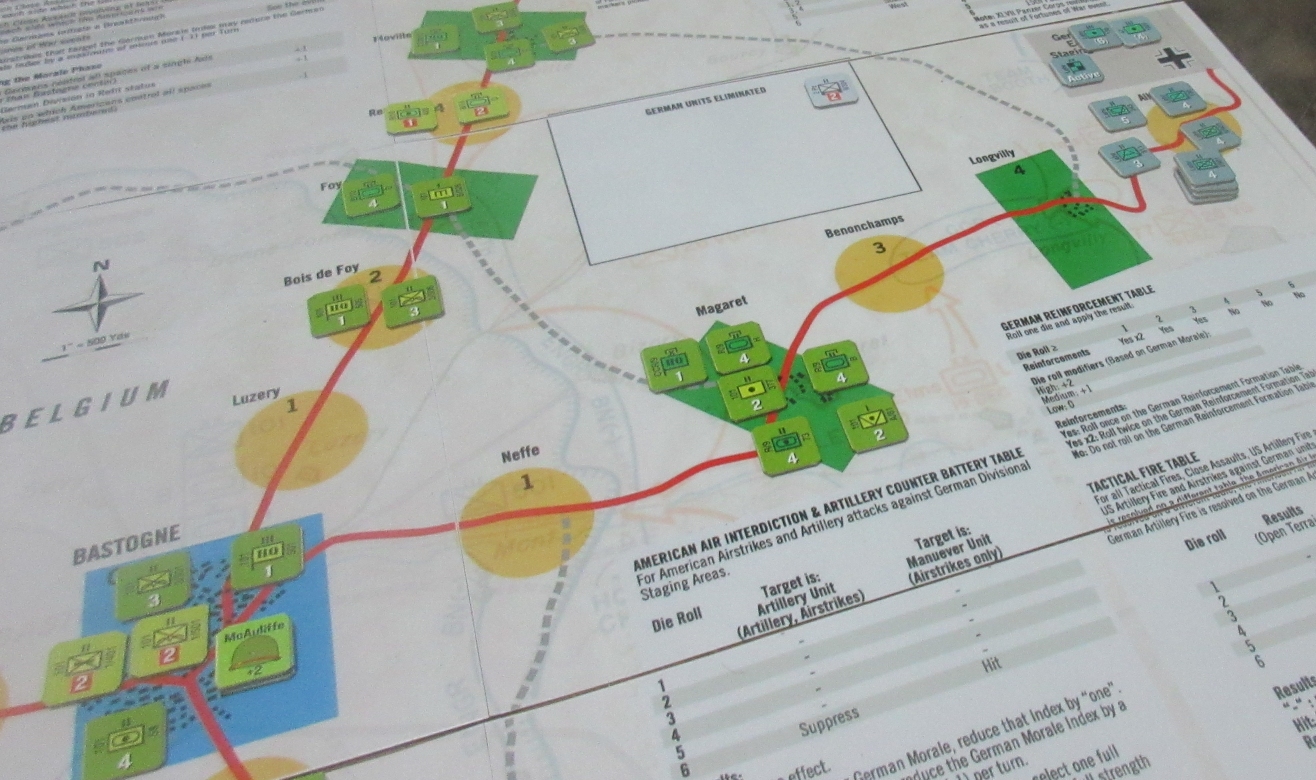

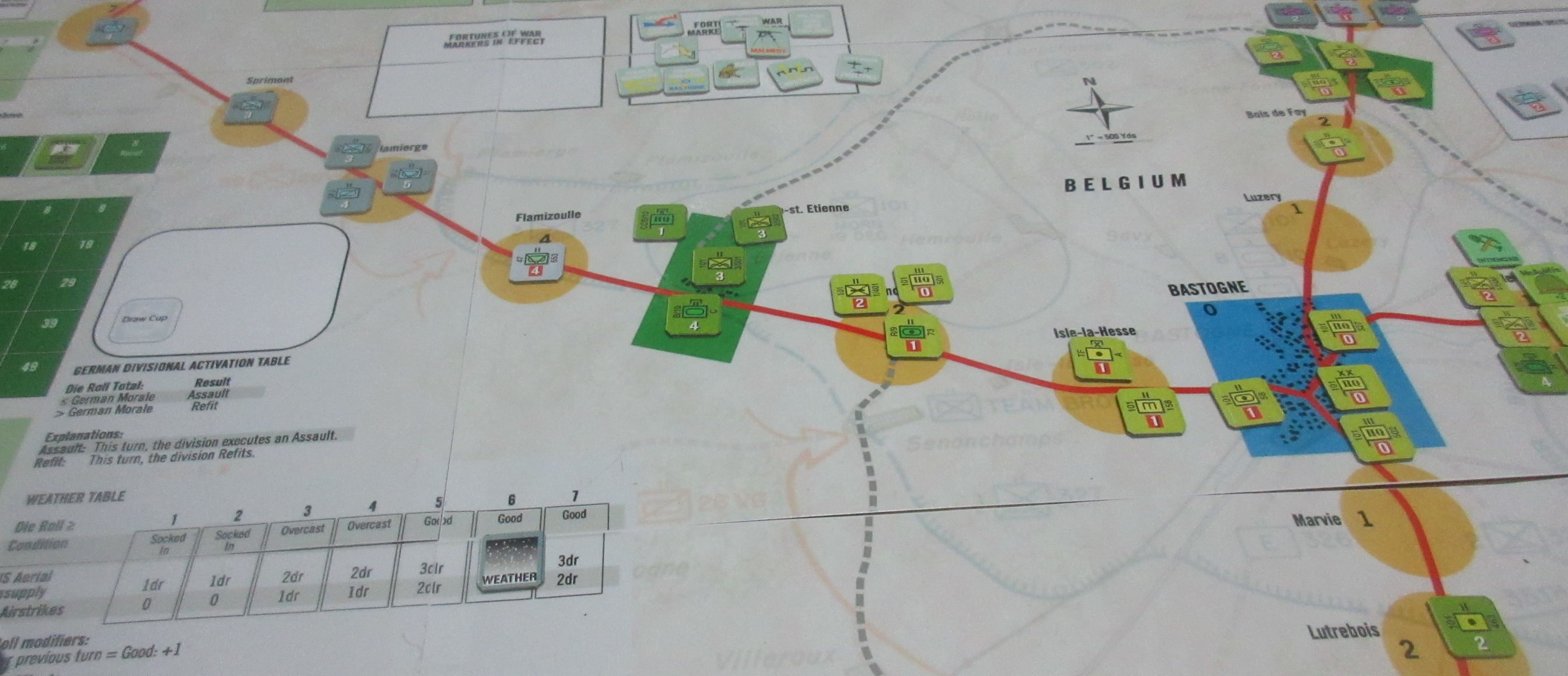

The map may surprise if you are used to standard hex or area games. It has four tracks converging on Bastogne. Each track is divided into several zones and has a German staging area at its outer extremity. Zones can be either plains, town, or Bastogne. Under these tracks there is a faded topographical map of the area. All the tables required to play are on the map itself. While the reprint (shown above) issued through Banzai magazine came with much nicer art, I find the original’s visuals perfectly serviceable.

Well organized, logical, and with minimal errata, the rules allow newcomers to get into the game very quickly.

A lack of player agency – a criticism often levelled at solitaire games in general, and States of Siege titles in particular – isn’t an issue here. The poor, surrounded, and often outnumbered American player has plenty of decisions to make. Not only does he have to reinforce threatened sectors, and decide how deep his defence should be, critically, he has to decide where to defend. There are trade-offs almost everywhere. A decidedly forward defence can protect Bastogne for longer and decrease German morale, but at the cost of being closer to German staging areas, and thus being constantly under pressure. Drawing one owns forces closer has tactical advantages, but also means losing control of the lateral roads surrounding Bastogne – arteries quite important for quickly shifting reinforcements from one axis of advance to another.

Terrain also plays an important role. Towns and entrenchments are critical to unit survival. They provide the ability to ignore retreats, hold the box in case of a draw in close combat, and give an advantage in determining who fires first in close combat.

Finally there is the crucial matter of supply. As this comes by air, it’s heavily dependent on favourable weather. Supply points allow you to refit reduced units, use your artillery in various roles, improve your combat factors, your movement, and build entrenchments. The system has sufficient nuances to force you to balance priorities and think hard about decisions. In Bastogne you are no sleepy passenger along for the ride. The player is very much in the driving seat. Whether you make it to your destination or perish in a spectacular crash, is down to you.

The Germans may seem robotic at first, but what they do makes sense. Their actions are controlled by their morale. The higher it is, the higher their operational tempo, the better their ability to refit reduced or eliminated units, and push forward. In consequence, a wise player will do their utmost to keep German morale low. Reasonably enough, German morale increases when they destroy American battalions, capture spaces, and make gains, and is eroded by losses and battlefield reversals. High German morale also negatively impacts the ability of the US cavalry (George Patton’s 3rd Army in general, the 4th Armored Division in particular) to relieve besieged Bastogne, and, in an ingenious twist, actually reduces the chances of German reinforcements.

While the game is not a perfect simulation, it does, I feel, manage to put you in a position similar to that of General McAuliffe. You will pray for good weather. When the weather is “socked in”, the worst possible result, you will have no air support and very few supply points. Even worse units lose the ability to perform ranged fire. This means that you will not be able to perform defensive fire before the German close assault phase. If German morale is high and there is a good sized attack force in position, that could spell disaster.

The game clearly shows the predominance of defensive firepower. Usually the defender fires twice, once in the tactical fire phase after the attacker movement, and then in close assault. The attacker may fire first in the latter, but a properly prepared defensive position will give sufficient die roll modifiers to swing the odds of getting the initiative to the defender. Bad weather, bad decisions, and bad rolls can ruin the best of plans… yet reading histories of the battle the linkage between bad weather and attacker success is undeniable. This is true for both sides. Attacking the German spearhead in bad weather, especially if they are in the open, and you have command bonuses to improve your chances to get the tactical edges, is a sage tactic.

While Bastogne has perfect intelligence on the map, fog of war isn’t entirely absent. Not only do dice rolls create friction and unpredictability, but events also contribute chaos. Each time a battalion or more is destroyed in combat, or the Germans take a town, a fortune of war marker is drawn from a cup. These markers represent High Command decisions on both sides, local events like scratch reinforcements, and unpredictable developments like the appearance of the Luftwaffe (Yes, Goering’s boys did indeed show up over Bastogne). Of particular note is the swinging mood of Der Fuhrer and his OKW in regard to the operation. Fickle berlin can order another effort to take the town (increase in morale and reinforcements), or divert resources for a push toward the Meuse. Historically it did both at different moments of the battle, and the game may perfectly replicate that, or it may not!

The aspect of Bastogne that left me coldest is its combat system. The game uses the old tried, trite ‘bucket of dice’ approach. You roll a multitude of dice, scoring hits on sixes, and, sometimes, fives. I’ll be upfront – I hate buckets of dice. To me it’s a hallmark of bad design. An approach common with miniature games, some say it represents massive amounts of ammunition expended for little results. Other proponents say it increase the narrative element, or like it because its faster than look up charts. To me these explanations are, frankly, rubbish. A stronger defence of the approach highlights its supposed ability to even out luck. But the soundest defence of the system I have ever encountered was from Harold Buchanan, designer of Campaigns of 1777 .

In the designer notes of that game, Buchanan made the persuasive argument that this approach allows for better scaling of losses. In games when clashes involve everything from small detachments to full size armies it is, according to him, the best way to resolve combat. He furthers his argument, providing an optional table where, after counting firing factors, only two dice are rolled to determine hit, exploiting the bell curve effect of the sum of two D6. Personally I think that his defence of the bucket of dice is the only one that makes any sense.

Yet the main issues with the system remain. Rather than flatten luck, buckets of dice can magnify outlier results. In Bastogne, on one occasion, for a German firing I had to throw 26 dice… and ended up getting a completely ludicrous number of hits. If Tim disliked the dominant dice in Mark Herman’s Gettysburg and Waterloo, playing Bastogne will have him screaming in pain. Noisy, messy, and hard on wrists, en masse dice rolls are tiresome to execute and do not produce the evening out that is sometime referred as the casino or Monte Carlo effect, until plenty of massed throws are made. Bucket of dice system are also very difficult to calibrate due to their inherent variation. To get them producing reliable averages you need to play tens if not hundreds of playtest session, and my personal experience is that this is not possible for the majority of games, certainly not for magazine games.

There is also a mechanical/logical problem in the bucket of dice approach, especially ones that just add dice. It tacitly supports the discredited Lanchester laws of combat*.

* Frederick Lanchester (1868-1946) formulated a series of equation trying to predict WW1 air combat in 1915. His approach was that the more planes you deploy in a fight the more kills you will score.While Lanchester’s Laws of Combat are still widely used in military operation research, they have been proved invalid.

In Bastogne each unit has a combat strength representing the number of dice the unit generates. For example, a heavy tank destroyer battalion is 6, while an infantry battalion is 3. That means that two infantry battalions have the same combat ability as one TD. At their most extreme, Lanchesterian combat models suggest that if a British Army Challenger 2 MBT has, say a value of 100 and a man with a javelin (the original variety, not the missile) a value of 1, then 100 men with javelins equal one Challenger II.

If this sounds silly, it’s because it is silly. It ignores the fact that the more force you cram into a single space, the more this force becomes vulnerable to enemy fire. In Bastogne the combat system does exactly that. It encourages massing forces without any penalty except stacking limits, and fails to acknowledge the specific strengths and weaknesses of units, their interplay, and their relationship with terrain. For example, a tank unit is as effective in close terrain as open. You can argue that units represent combined formations with some cross-attaching instead of pure battalions, and to a certain extent it is true, but I still feel Joe Miranda could have employed a better combat system.

In my opinion a better solution to the issue of large variation in strengths is the fire point approach and the two or three d6 sum table. There are variations of these tables that even cater for modifiers. A solution such as this would not only would have been easier on the wrist, it would have allowed players to gauge likely combat outcomes more easily, and reduced the occurrences of unbelievable results. Using the table Harold Buchanan provided in Campaigns of 1777 would go a long way to solve the combat problem.

Yet despite the flawed combat resolution system I still found Bastogne to be enjoyable and credible, and would wholeheartedly recommend it, especially with the combat system modification suggested above. Original versions of the game are hard but not impossible to find nowadays, but with a Vassal module and English rules freely available, anyone curious about Bastogne can satisfy that curiosity pretty easily.

Very interesting to hear about Lanchester’s Laws. I wonder if there’s some similar 20th century examples from the likes of the Rand Corporation where false assumptions were developed into misleading theory.

This SGS Bulge game released last December looks fascinating:

https://store.steampowered.com/app/3265620/SGS_Battle_of_the_Bulge/