For today’s interviewee, wargames aren’t just entertainment founts, they are educational aids. Historian and wargame designer, Arrigo Velicogna has used interactive guerre sims to help War Studies students at King’s College London “understand the interplay between various dynamics in a conflict”.

THC: Do you remember your first encounter with a wargame?

Arrigo: Yes, I was quite young at the time, still in elementary school, and I saw some wargames from an Italian publisher, International Team. I was able to persuade my mother to buy me one for my next birthday. It was called Sicily ’43 and the topic was Operation Husky, the invasion of Sicily. I took some time to properly figure it out, and then I realised it had a fatal flaw in the victory condition that a clever Axis player could ruthlessly exploit to force specific allied moves. Around 40 years later I realized it had a lot of other issues too. Yet at the time I played the hell out of it for years. More to the point it hooked me to the hobby. And when I realized there were more games, and the majority with English rulebooks, I decided to study English seriously.

THC: If you hadn’t gone into academia, what do you think you’d be doing now?

Arrigo: Academia was not my first choice, it was almost a chance encounter. My original choice was an Army career. I entered the Italian Army Military Academy but had to drop out for a medical reason, then I had to do soul searching, a lot if it. Dissatisfied with prospects in Italy I ended up applying to King’s College London. I got accepted and met professor Philip Sabin as a result. At the time I was still oriented toward a military related position.

I am from a long line of teachers and I always wanted to stay out of school so I was not thinking about academia. But then Phil and the late professor Saki Ruth Dockrill, and Colonel James Willbanks, US Army, Ret, (at the time the head of the military history faculty at Fort Leavenworth) encouraged me to apply for a PhD. The funny thing is I got in contact with Colonel Willbanks for wargaming purposes, I was looking at information on the South Vietnamese forces at An Loc in 1972 for the wargame I was designing as part of Phil’s class. In the course of the PhD I ended up teaching, often assisting professor Sabin and I realized I am good at it, so I took that path. The choice was, in part, motivated by my ability to merge wargaming with proper military history and strategic studies. We have plenty of Strategic Studies/Military History experts who cannot really understand military operations, and plenty of professional wargamers who limit their research to Wikipedia. My expertise should be a job winning combination, but despite what other academics have told me, in the current, post Brexit, post pandemic world, I am not 100% sure!

What would I have done if I hadn’t chosen this path? To be honest I have no idea, also because to work as consultant for the military you need to show some academic credentials. My original degree is in Ancient History and I was looking at archaeology, but again, I ran away from Italian archaeology.

THC: If the average Cornerite had attended your last KCL lecture, do you think they would have found it interesting?

Arrigo: Well, my last lecture at KCL was for Phil’s Conflict Simulation Module, the last year it properly ran. I suppose Cornerites would have found it interesting. It was focused on CRTs, Combat Results Tables, and other design aspects relating to the complexity vs realism vs detail issues. It was a staple of my work for Professor Sabin. For the former I was explaining how to capture the vagaries of combat in a simplified system you can actually use in a game without wrecking your brain and your calculator. And then the usual designer’s conundrum. These three words, Complexity, Realism, and detail always seem to be confused and misread. Add to that that as often in human activities there is a lot of subjectivity involved.

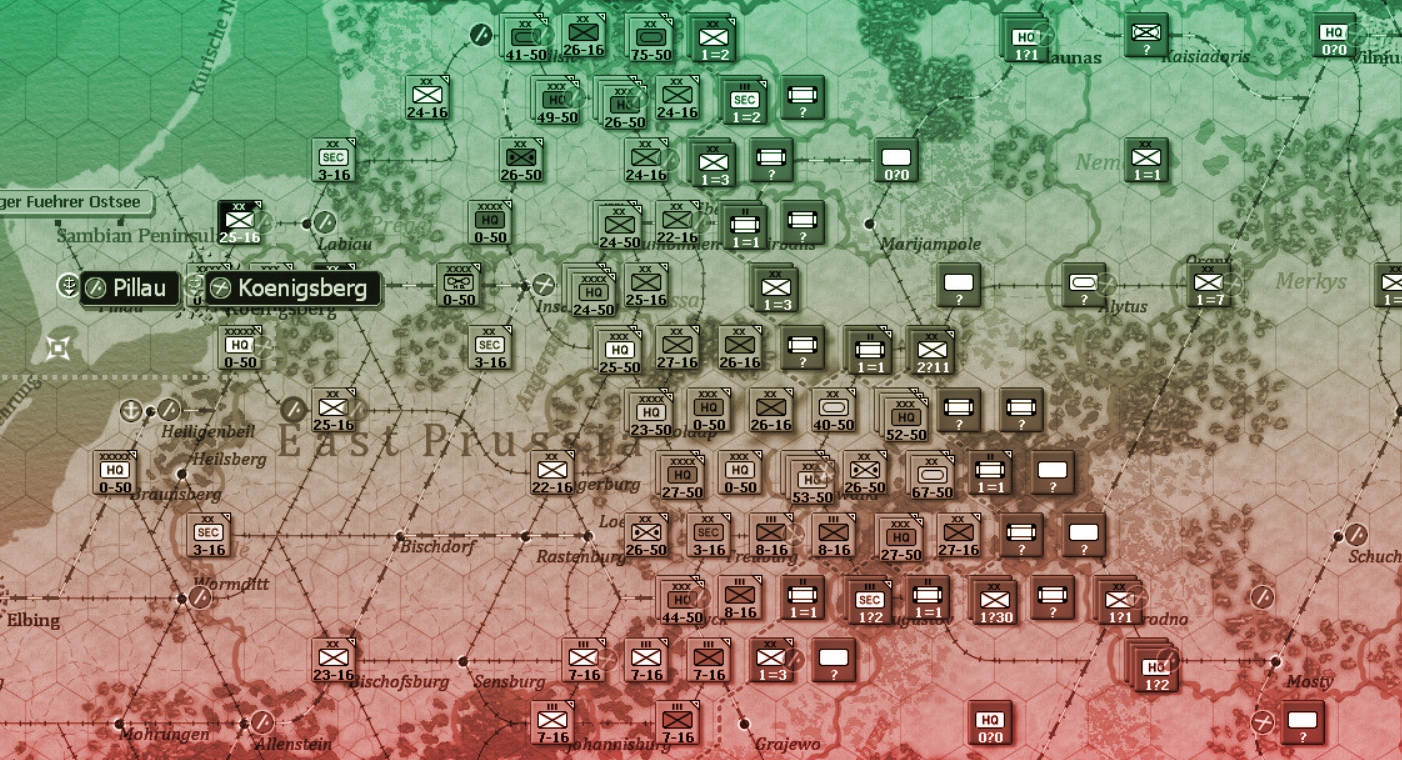

I still remember an old Flare Path discussion on Phil’s Simulating War and its games and the idea that a more detailed computer Russian front game would be better than his East Front II and more realistic. Now I am a big proponent of manual over computer wargaming, more on that later, so I am biased, but there the issue was not realism, but details. Plenty of people equate detail with realism, or realism with real life. Both equations are largely made up. Often I have encountered the sentence “if you want a realistic wargame go to war” or “we are just playing games no need to take them seriously”. I have also encountered people who wanted to resolve combat in operation games with ASL scenarios. Detail and Realism are not the same thing. Eisenhower for example did not fight in the frontline and did not give orders to every Allied squad in Europe. The equation is much more complex, there is appropriate and inappropriate detail, necessary and unnecessary complexity, and realism is more a reflection of the experience you are trying to create than anything mechanical. That would put several games under a different lens. Which is more realistic, Grigsby’s War in the East II, Phil’s Eastern Front II, or maybe Masahiro Yamazaki’s War for the Motherland? That is the tricky question a serious wargamer should always ask him or herself.

THC: Have you ever used off-the-shelf wargames as teaching aids?

Arrigo: Yes, several times, all manual wargames, almost always not my designs. Earlier I said I believe manual wargames are better. Let me explain why I made the statement. Computer wargames are nice, I own plenty of them, play them, and still buy them, but as teaching tools they are not the best medium, at least in the environments I’m familiar with. From the teacher’s perspective they are black boxes, I cannot make any changes to them, and the whole system is kept away from the students. For the students, well it is a solo or small group experience, something that it is difficult to do in class. From when I started as a teaching assistant in 2009 to today, classes and seminar sizes have steadily increased. Some would say without control and to the detriment of the students. There is also the element of the purpose of the game. Do you play a game to train the student on tactical/operational maneuvers, or to understand what is happening and why? The former is well suited to digital games, and is why the military often settle for off the shelf games. In universities the latter is what you do. You use a game to show the students the interplay between various dynamics in a conflict. I will provide some examples.

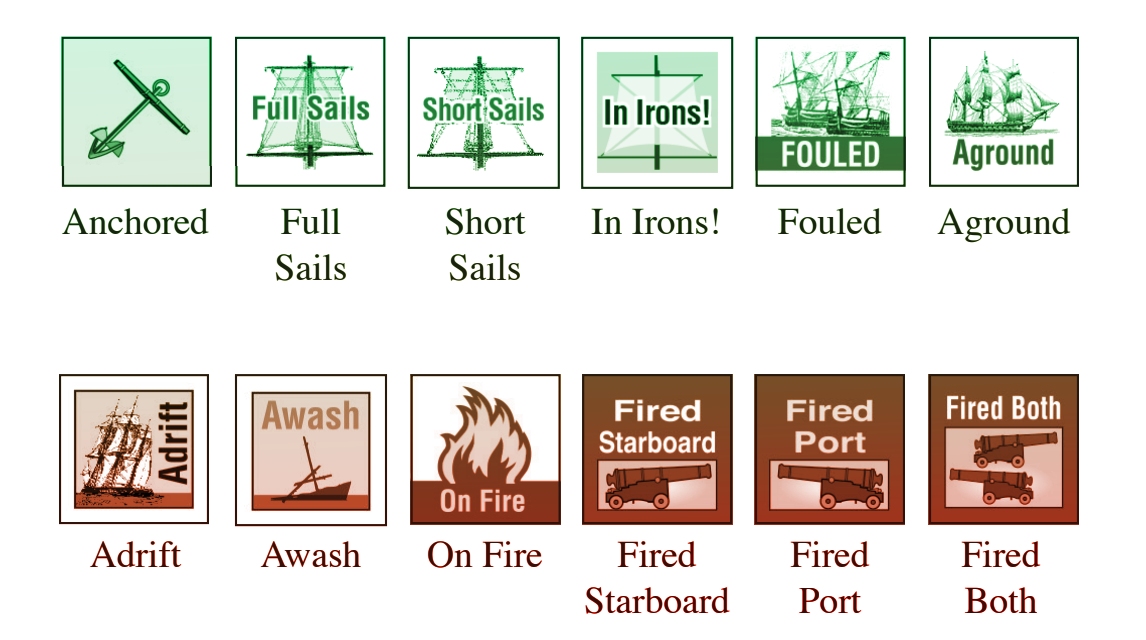

For Naval History’s students I hosted a game of GMT’s Flying Colours using a small scenario. I was able to give a single ship to each student and they did the maneuvering while I was taking care of the rules. Why? When you are discussing age of sail naval warfare few students have any idea of what was really happening. I cannot take the students back in time, and even if I could, the Admiralty would never give us a ship to skipper. A serious wargame is the second best option. In this case the aim of the session was to understand how ships were fighting, why line formations were adopted, why these formations were not that easy to keep, and why battles in the period were often inconclusive. There was a tendency from some other teachers to put too much focus on political and social explanations without looking at reality. The wargame helped me in providing a counterpoint.

For XVI and XVII century sieges I used a free game from the Perfect Captain website, Spanish Fury, Siege! The main lecturer had left the impression that sieges were more a political than a military endeavour failing to convey the military realities. The game is quite simple, I made some small modifications, and I was able to show the decision making and the trade offs involved.

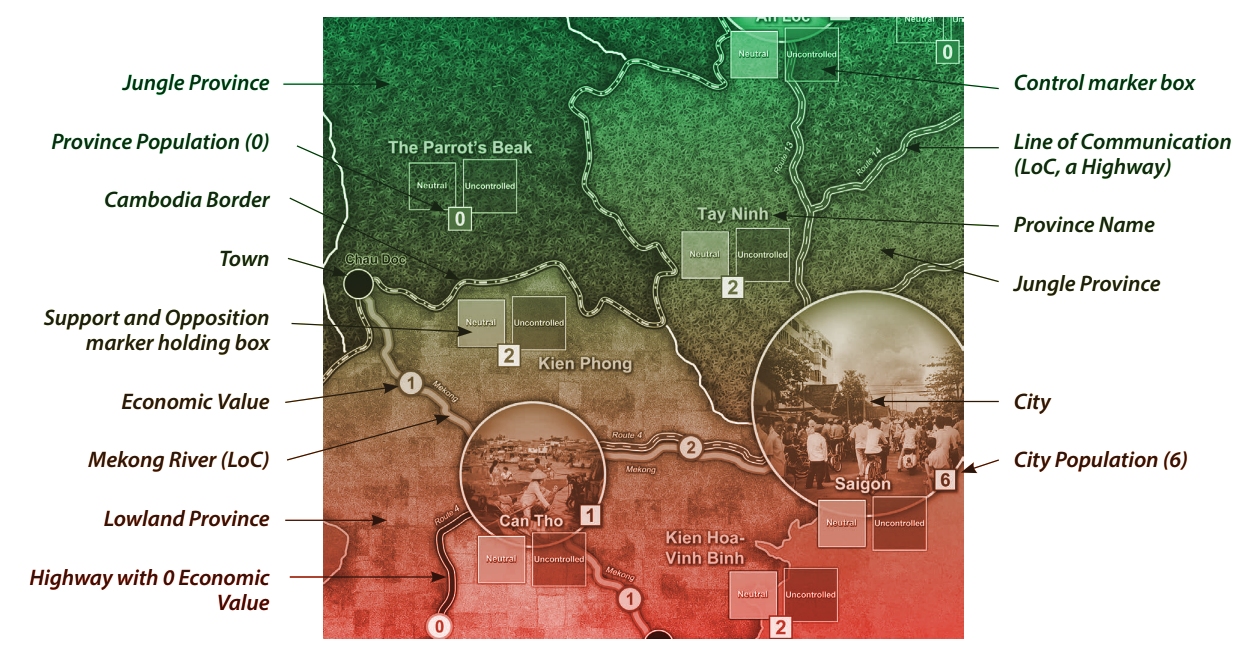

For a counterinsurgency module I used both Legion Wargames’ Ici C’est La France and GMT’s Fire in the Lake. I was interested in showing different models of insurgency and counterinsurgency and how theory works in action. One of the main issues I have with teaching is the reliance on theories by our sources. Too often theories are accepted on the basis of “proof by assertion”. The advantage of wargaming is that a theory should at least work in the game.

My general approach is to use games to show decision making process. Too often authors tend either to present events as foregone conclusions or make criticisms of decisions without making proper allowance for constraints. The classical case is Guderian – plenty of followers criticise the Kiev’s diversion. Or criticising Dien Bien Phu… in my last year of full teaching in a module where I had too many students to get them around a map… we had to change classroom at the last minute because the one I was assigned was too small… I used what the US military calls Tactical Decision Making Games and the British Army Course of Action Gaming. You give the mission and the resource and then the ‘players’ propose their plans. The subject was indeed Dien Bien Phu. It was incredible to see the students, graduate students including a couple of serving officers, choosing Dien Bien Phu, but more interesting to see the explaining their choice, and also their critique of General Navarre’s reasoning.

Yet games are a tool, not an end. You should always follow the game session with discussion. What did we learn from the game? But also what do we think of the models underpinning the games themselves? Discussions are even more important than the games themselves. It also takes us to the reason why I tend to avoid my own games. It is important to let the students critique not only their decisions, but also the model. Games are models created by human beings. This means preconceived biases, assumptions, and choices. When I was still an assistant, I saw the pitfalls of going defensive over one’s own game. I prefer to not have a horse in the race, so I do not have to defend my design choices to the extreme.

THC: Have any of your students entered the games industry and would you consider making such a move yourself if an opportunity came along?

Arrigo: One of my former students should have her game on Operation Chromite published by either Tiny Battle Publishing or Flying Pig Games (two sister companies). Another, from the same class and team published a wargamer’s guide to the Battle of Leipzig with Helion last year. Finally another student was already working in the digital gaming field at the time I met him, he was also a British Army Reserve officer. It is important to note that my students usually came from humanities or social sciences background, like myself, so the digital field, especially as far coding is concerned requires a different set of skills. But I and other Conflict Simulation Alumni have published several traditional wargames. In my case a new Fulda Gap title should come out soon.

Sadly, a certain percentage of students are in a module more for the grade than anything else. That applies to every module I taught or even attended when I was a student. It is a sad by-product of increased intake but also previous indoctrination. I had students who dropped out of a module because the subject was different from what the student already knew. Graduate students at times are already entrenched in their beliefs and pointing them to something else is difficult, almost impossible.

THC: The Vietnam War is clearly a subject close to your heart. In your opinion which games capture the character of the conflict best?

Arrigo: This is a difficult question to answer, in large part because it was a complex conflict, and one that has been projected into popular culture through specific lenses. There is too much rubbish talked about counterinsurgency, often from not overly reputable sources, Karnow and Nagl for example, masking the actual war. I would say the best strategic game on the subject is certainly Bruce Costello’s Victory in Vietnam II. Sadly, it is out of print, but certainly could benefit from a new edition from one of the “big” publishers. It successfully captures the political debates in Hanoi and Washington and provides players with an excellent large scale overview of the war in the ground and in the air. It is more abstracted than many would expect but it works.

Then you have the dean of operational Vietnam wargames, Vietnam 65-75 from Victory Games and now GMT. I have some issues on its portrayal of South Vietnamese politics, and it kept theater strategy out of your hands, but it really puts you in the combat boots of Westmoreland/Abrams on one side and Giap/Tung on the other.

Focusing on different aspects of the war I also like Downtown a lot, a really nut and bolt operational take on the air war over North Vietnam. At the operational level Decision Games’ Winged Horse has probably the best system I have seen. It is limited only to 1965-66 period, sadly.

For grand tactical and tactical approach, Campaign Series: Vietnam from Matrix/Slitherine and the two WDS Squad Battles titles on Vietnam are difficult to beat. Also Mitchell Land’s Silver Bayonet Deluxe edition from GMT. Best game of the Ia Drang campaign. These are usually my go to games on the topic, and no, I am not including my own An Loc despite being an excellent game!

I would also like to mention two games that while affected by issues have potential. MMP’s Front Toward Enemy has one of the best tactical systems for Vietnam I have ever seen but is marred by a poor approach to scenarios. Decision Games’ In Country, Winged Horse’s big brother, is let down by the absence of an ironed-out campaign system. The designer, Joe Miranda, has promised a new deluxe edition… let’s wait!

THC: Do you think it matters if wargame designers inadvertently sanitise their subject matter?

Arrigo: Inevitably we do. To a certain extent is because a wargame is a model based on several abstractions and focused not so much on actual combat as on tactics. Sending armies to the front is sanitising warfare without any doubt, but to a certain extent this is what warfare is away from the frontline. Once I participated in a professional gaming session on the Falkland Wars. I was the Argentinian player. My opponents were none other than Major General Julian Thompson and Commodore (Captain) Michael Clapp. They were refighting their own decisions. At command level we are not sanitising war. A brigade or division commander does not send Private James to attack a machine gun nest, we send the 2 Para to take the town. Of course there are exceptions.

Back in time GMT’s Victory in the West had refugees counters with women and little kids on them generated by the German advance in France. When you see an entire town emptying and moving west you start to realise it was not just an exercise in moving panzers and chars de bataille. Lee Brimmicombe-Wood’s Bomber Command did not shy away from the carpet bombing of German cities and its results. Some of us designers can avoid trivialising the subject matter. Shayne Logan in his upcoming Afghanistan game will deal with civilians and collateral damage too. And these are just some examples. The issue is not so much involuntary sanitising, but having your audience forgetting what is happening in the game. You should know the subject matter. To a certain extent if we take a game on World War II to Romulus and have two average Romulan players (beware Star Trek fanatic here…) playing it they will not realise what is involved in the Japanese playing the Three Alls Policy chit. But as long we provide sufficient historical information to make these connections, I do not think we are trivialising or sanitising history. A much worse case are war themed games that paste on a theme without properly engaging with it.

(^ liveuamap.com)

THC: How closely are you following events in Ukraine and what impact do you think they will have on the War Studies sector?

Arrigo: I try to keep abreast of them, but I have to admit that it has become almost impossible to get real information opposed to propaganda claims. You need to follow trends for months before getting some useful analysis. I am afraid to say that even supposedly reputable sources have engaged in the propaganda game. Yet there are plenty of useful considerations. I would say that the war has vindicated my approach to war studies. We are seeing a conventional, mechanized, and attritional conflict with large expenditure of blood and ammunition… something some in the field had claimed for years was impossible. In the past 10-15 years I have seen a fascination with alternative warfighting methods or alternative warfare creeping. Between military revolution’s preachers and colleagues literally snubbing military affairs and focusing only on politics and societal issues there was a growing consensus that fighting war was… passé. That despite growing evidence of the contrary.

What I and others have seen is a concerted push toward morphing War Studies into Security Studies. There are many reasons behind this – ideology, lack of expertise, and previous approaches – but it also shows a tendency to ignore contrary evidence. I got the impression that in academia the current war is considered an outlier and a rare event. The military side is more interested in what is really happening in the field, but seems to have been caught completely unprepared. As I was once told at the RMAS Sandhurst there is a fascination in devising methods to fight wars bloodlessly. Manoeuvre is revered, attrition is eschewed. What is worse I have seen growing expectations that the enemy will respond to brilliant manoeuvring by accepting defeat. Now, do not get me wrong, plenty of professionals have much less rosy expectations. I was standing beside a Major General while he was telling young officers that they could not expect German eastern front veterans to collapse and surrender only because they had turned one of their flanks. But recently the Chairman of Joint Chiefs of Staff in Washington claimed to have been taken by surprise by the ammunition expenditures in Ukraine.

At the same time the former Commandant of the US Marine Corps, General David Berger, has planned to fight a war against China based on using small units with a few precision guided munitions. To prove himself right he used wargaming, but creating scenarios to prove the concept right rather than stress-test it. Have a look at the commercial version of the effort, Littoral Commander Indo-Pacific and its scenarios. The PLA is fighting exactly as the Marines want it to. I would be curious to see a Chinese take on the same topic, I know a Chinese designer is working on it, but I am not sure the game will be available in English.

Ukraine is important and we are all analysing it, but I am not so sure lessons will be retained.

THC: If someone thrust £100K into your hand, and said “Go make a digital wargame about any subject you like” what theme would you choose?

Arrigo: A strategic game on Vietnam! I do not see any on the market, I have done the research, and believe it would be challenging and relevant. But I’d also keep £10k in my bank account.

THC: Do you prefer to computer wargame alone or against human opponents? And what is more important to you – a tough AI or a plausible one?

Arrigo: Usually, I play alone so AI is my standard opponent. It should be noted that usually I look more at the immersion factor of a title than the AI. But I prefer a plausible AI to an abstractly efficient/tough one. I have played against friends and those games have been memorable at times, but more for the banter on the voice channel. I still remember a ridiculous moment playing a red-on-red scenario in Combat Mission: Shock Force with a Syrian rebel AT gunner always hiding from my government T-72 when its turret was rotating… and me and my opponent yelling at both of them. I have to say that to me the experience was more akin playing miniatures remotely than proper PC gaming.

I also play a lot of games on Vassal or Tabletop Simulator, either for testing or just fun. It is a great way to play with friends who are not within car-driving range.

THC: What was the last wargame that you purchased? Did it live up to expectations?

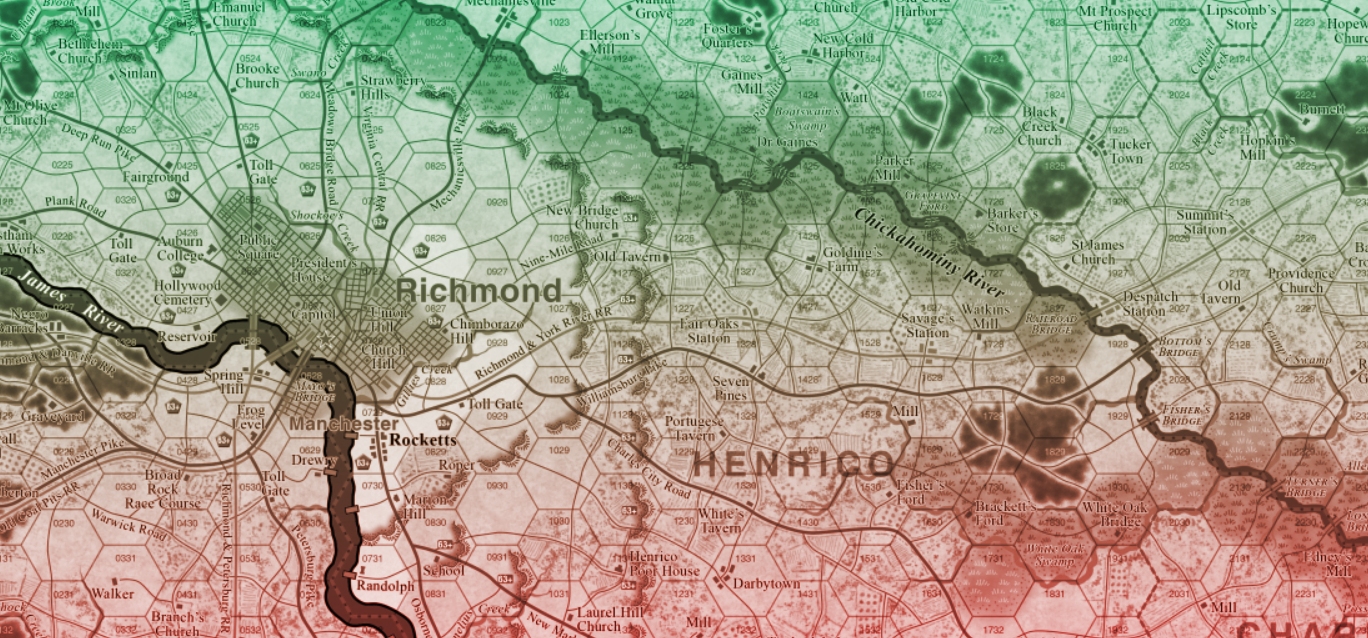

Arrigo: On To Richmond II from MMP. It arrived after the customary customs ordeal, and still has to hit the table, but I’m confident it will be a great ACW operational title. The Great Campaigns of the American Civil War series has never betrayed my expectations.

THC: Name a game, either released or unreleased, that you feel deserves more attention.

Arrigo: For released I would say Old School Tactical (Flying Pig Games). For unreleased… difficult, let’s say Bruce Maxwell’s Air and Armor from Compass.

THC: Thank you for your time.

Quite enjoyed that interview. Thanks Arrigo and Tim!

I enjoyed reading this interview. Plenty of interesting views and ideas.

“From the teacher’s perspective they (i.e. Computer war games) are black boxes, I cannot make any changes to them, and the whole system is kept away from the students”. Perhaps the need to shape the pc game user experience, and break open the box, is one reason why modding is so popular.

True, but in my typical class environment it would be completely unsuitable. Said that there is also the issue of how much you can mod. More often than not the core engine is not moddable. Thus the changes are more ‘cosmetics’ from this point of view. Now I am perfectly aware of plenty of extremely deep mod available for extremely deep games but these require time, expertise, and commitment. Learning the engine of a map and counter game, or even a miniature one is much easier. From an analysis perspective this allows you critiquing it, and if necessary modify. But of course the latter is more suitable to design classes. Yes PC games are easier to get in because the PC is literally working everything for you, but that makes them less suitable for an educational environment.

Wonderful interview! Found this very interesting, with some great thoughts from Arrigo.

Seconded.

Thirded. I prefer playing cardboard wargames myself, and Arrigo expressed the difference better that I could have: to understand what is happening and why.

Love to hear more from Arrigo. Will be looking into his designs.

Thanks for the feedback. It’s good to know there an audience on the Corner for this sort of thing.

Fascinating stuff all round, thanks Arrigo and Tim for the insight.