I am currently in possession of the Nineteenth Century equivalent of one of those preloaded retro games consoles. While I knew I wouldn’t be able to use it to vapourise alien spacecraft, fragment drifting asteroids, or leap rolling barrels, I rather hoped it would allow me to – after a fashion – wargame.

On loan from a neighbour who thought I’d be interested (Thanks, Nigel!), this box of delights is approximately 32 x 22 x 17 centimetres in size and 4.5 kilograms in weight. Like all the best consoles, it’s made from oak. On its two most conspicuous surfaces, that oak is overlaid with turbulent walnut burr veneer. Curious children/servants are kept at bay by a small but effective half mortise lock. A clockwise turn of the key that fits that lock, frees the box’s perfectly fitted lid and double doors.

Opening the wooden treasure chest for the first time, it’s hard not to let out a little “Ohh!”. There in front of you, like toy soldiers on parade or effigies on some portable altar, are 32 chunky Staunton chessmen. Turned from best Buckinghamshire beech, and kept in place by discreet shelf pegs, the glossy warriors lead the eye to a pleasing cylinder of serried draughts pieces, beyond which a cribbage board sits. Nestling in the roof of the Lilliputian pleasure pavilion is a rule book and what appears at first glance to be a folded chess board.

Semicircular wire handles at each end of the cribbage board tray invite fingertips, and, sure enough, the tray does indeed lift out, revealing a colourful trove of cards, counters, and other accoutrements in the partitioned chamber below. Naturally, none of the box’s contents are made from plastic. Bone, ivory, mother of pearl, cloth, wood, lead, brass, leather, and cardboard were the order of the day for game components in the latter years of the 19th Century.

Foxed and undated, the manual contains “general rules” only, for the compendium’s 38 entertainments. As the writer of the introduction points out “To have attempted more would have extended this little guide far beyond its limits. Our aim has been rather to help the would-be learner to acquire the rudiments, to instruct him in the rules, to familiarise him with the technicalities, and fit him for perfecting his knowledge by a subsequent perusal of some of the many works which treat exhaustively and scientifically of the matters we have dealt with popularly and briefly”.

Scanning the manual’s contents page, two games leap out at me. I leaf to page 21 to read about the promising sounding ‘German Tactics’, only to discover it’s a shallow Fox and Geese clone.

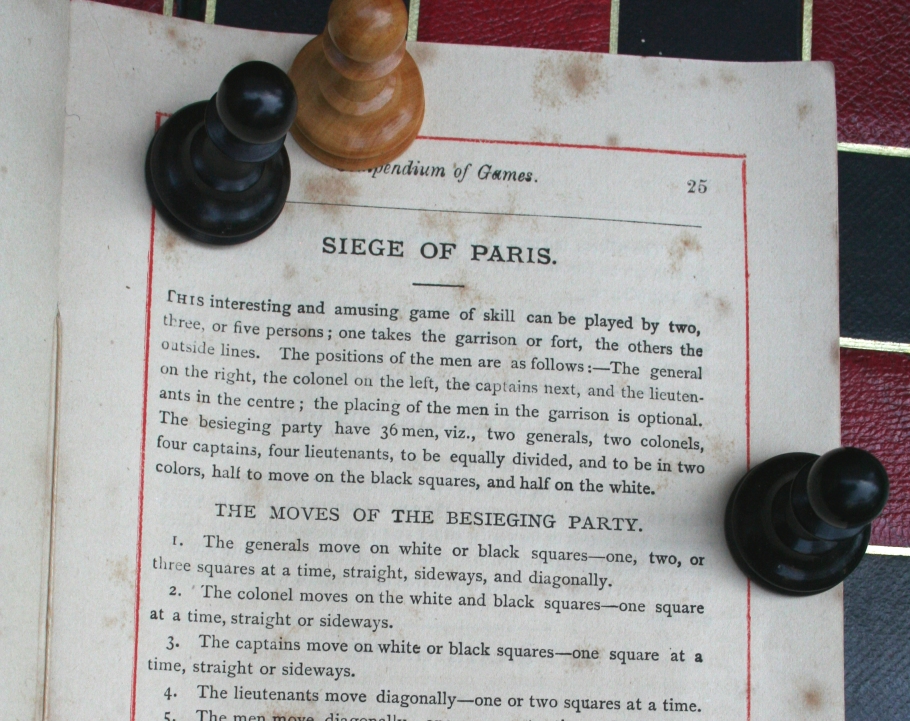

Perhaps the game outlined on page 25 will prove more interesting.

The arguably ‘too soon’ ‘Siege of Paris’ turns out to be an intriguing chess-like affair involving a heavily outnumbered defender battling two large attacking armies. Although, on paper the rules are hard to follow, after viewing this excellent instructional vid by David McCord, me and Roman are raring to play.

We begin emptying cloth bags in search of the relevant playing pieces, and unfolding and flipping boards in search of something resembling the board visible in David’s film. After several minutes of fruitless hunting, it dawns on us that this particular compendium isn’t as complete as it first appears. Evidently, at some point during the past century and a half, some inconsiderate blighter removed the copy of Siege of Paris! If we want to sample a pop parlour wargame of the late-Victorian era, we’ll need to make our own board and counters. Bah.

Maybe we’ll just play Steeplechase instead. Its hand-painted lead figurines are delightful and, perusing its rules, I see it models refusals and equine fatigue…

“When the points indicated by the dice lead the horse on one of the lines corresponding with the tens, or any number where the fences may be placed, he cannot stop there, but must return to his former number, and be called refusing a leap, thus losing a move which adds much to the excitement of the game… In order to proceed with more speed, two or four dice may be used, but in the latter case only two dice are used when the number 70 is obtained; and in both cases the play will be carried on by one dice only after the number 90 is obtained”

and encourages course editing!

“The difficulty of the course may be increased by placing in different parts the movable obstacles, such as ditches, hedges, and barriers”.

I like to imagine that copies of ‘Siege of Paris’ were requisitioned during WW2 to have escape equipment hidden within them before delivery to prisoner of war camps.

I was curious how these things might’ve been advertised in Victorian newspapers: were they mail order? meant for children or travelling? I have searched, but didn’t find any such hits so far.

The auction/asking price ranges from a couple of hundred to the frankly over-ambitious three grand; none of them mention or show off ‘Siege of Paris’ either.

However, I did land on this set of 200 auction lots from a Private Museum Collection Of Toys, Games & Juvenalia

https://bid.eastbristol.co.uk/past-auctions/sreas10549

I’ve only looked at the first page, and there’s some wonderful/intriguing stuff:

Spilli-Wobble – The Magnetic Mirth Game

1920s ‘Electro Tutor’ – metal studs on an unlabelled map of UK cities/towns; use the cable to connect it with the stud next to the name

1930s ‘Drake’ with its’ abstracted sea chart

Drake (1934)

https://boardgamegeek.com/boardgame/65843/drake

Drake looks great. The board puts me in mind of a tea clipper game I once brainstormed. In a nod to the revolutionary charts of Matthew Fontaine Maury, every hex on the globe-spanning board was to have a prevailing wind direction / sea current direction and strength.

I’d love to see digital ports of some of these old board games.