An encyclopedic knowledge of Warsaw Pact AFVs, Bob Dylan songs, Paris landmarks, or species of gibbon won’t help you solve today’s ‘foxer’. The singular co-op puzzle I’m about to describe was created during WW2 and has been steadily increasing in difficulty ever since. But for a chance detour a couple of weeks ago, I might never have stumbled upon it.

I was walking close to Salisbury Plain recently when the heavens opened. Realising I was going to get soaked to the skin if I stuck to my planned route, I decided to abandon footpaths and bee-line back to the car. My shortcut took me over a barbed wire fence, along the edge of a ploughed field, and into a strip of mature beech woodland that, judging by the dated detritus and tangled undergrowth, hadn’t seen human visitors in quite some time.

That the local squirrels, rabbits, badgers, and deer hadn’t always had this out-of-the-way place to themselves was clear from the graffiti carved into many of the larger trees. As I moved from dripping glade to dripping glade I passed numerous timber tattoos. The passage of time had rendered most of the inscriptions illegible but here and there recognisable words and numbers peeked out from under lichen rosettes and woody wrinkles. Scruting the scrutable, it eventually dawned on me…

I was walking through an accidental memorial arboretum.

Eighty years ago, in this bosky spot, soldiers from at least two corners of the Commonwealth on their way to fight, and possibly die, in North Africa and Continental Europe, had carved their names, ranks, and nationalities into living wood. As I squelched back to the car I resolved to return with a camera. I’d photograph the clearer trunk texts then attempt to decipher them with help from THC’s resident band of cyber sleuths!

Defoxers old and new, your challenge today is to help me confirm the names and unearth the histories of half a dozen beech tree brothers-in-arms.

The first bark brand I encountered on entering the wood was one of the most intriguing. Five paces from a trunk emblazoned with all four playing card suits…

…and a striking visage…

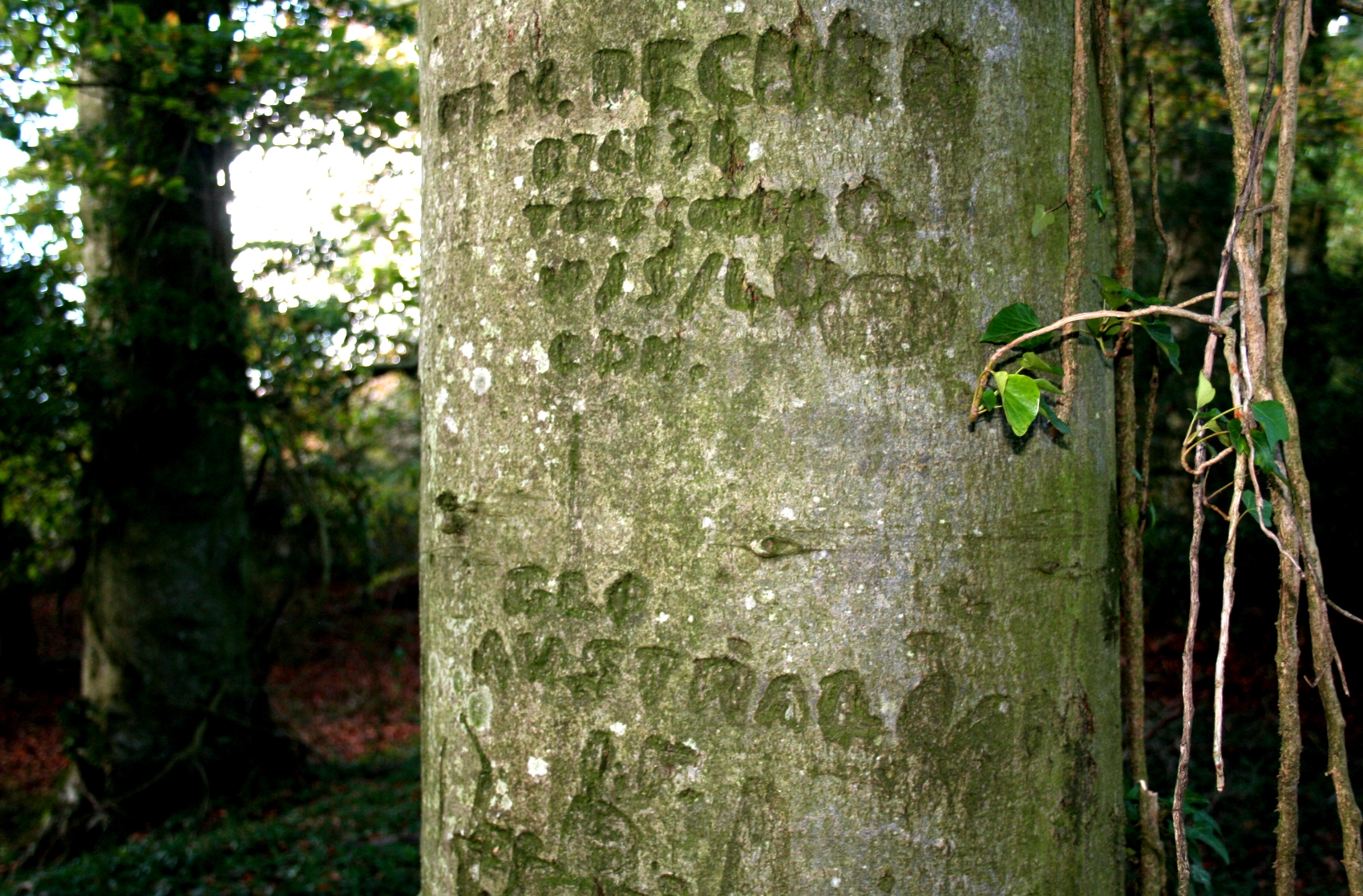

…was the pocket-knife scrimshaw of a PTE. Initially I read Soldier #1’s name as ‘M. DECHEA’, but later realised ‘M. DECKER’ was much more likely. The date three lines down appears to indicate the tree was defaced in May, 1940. Below the date are three letters – possibly ‘GDM’ (guardsman?) – above, a badly distorted string of letters that might have once read ‘TORSCOT’ (see on), and a six-character alpha-numeric sequence (B76134? B74139?) that could well be a regimental number.

Because, further down the same trunk, there’s a very clear “AUSTRALIAN I.F.” (Australian Imperial Force), ‘M Decker’ appears at first glance to be an Aussie. However, I’m now of the opinion the lower area of dendroglyphs are the work of a different soldier and ‘Decker’ was in fact Canadian. The fact that other carvings in the vicinity seem to be the work of Canucks, and the AIF didn’t begin arriving in the UK until June, 1940 lends weight to this theory.

A stone’s throw from ‘Decker’s’ handiwork is a terser effort unquestionably produced by a North American. Soldier #2 doesn’t seem to provide his name (I guess FV could be his initials) and his regimental number (?) is hard to make out (B53148? B53143?), but there’s no ambiguity as to his regiment.

The Toronto Scottish was one of the regiments that participated in the fiasco at Dieppe in August, 1942. Was ‘FV’ or any of his fellow graffiti artists involved in Operation Jubilee? If he was, did he manage to get off that infamous shingle beach alive?

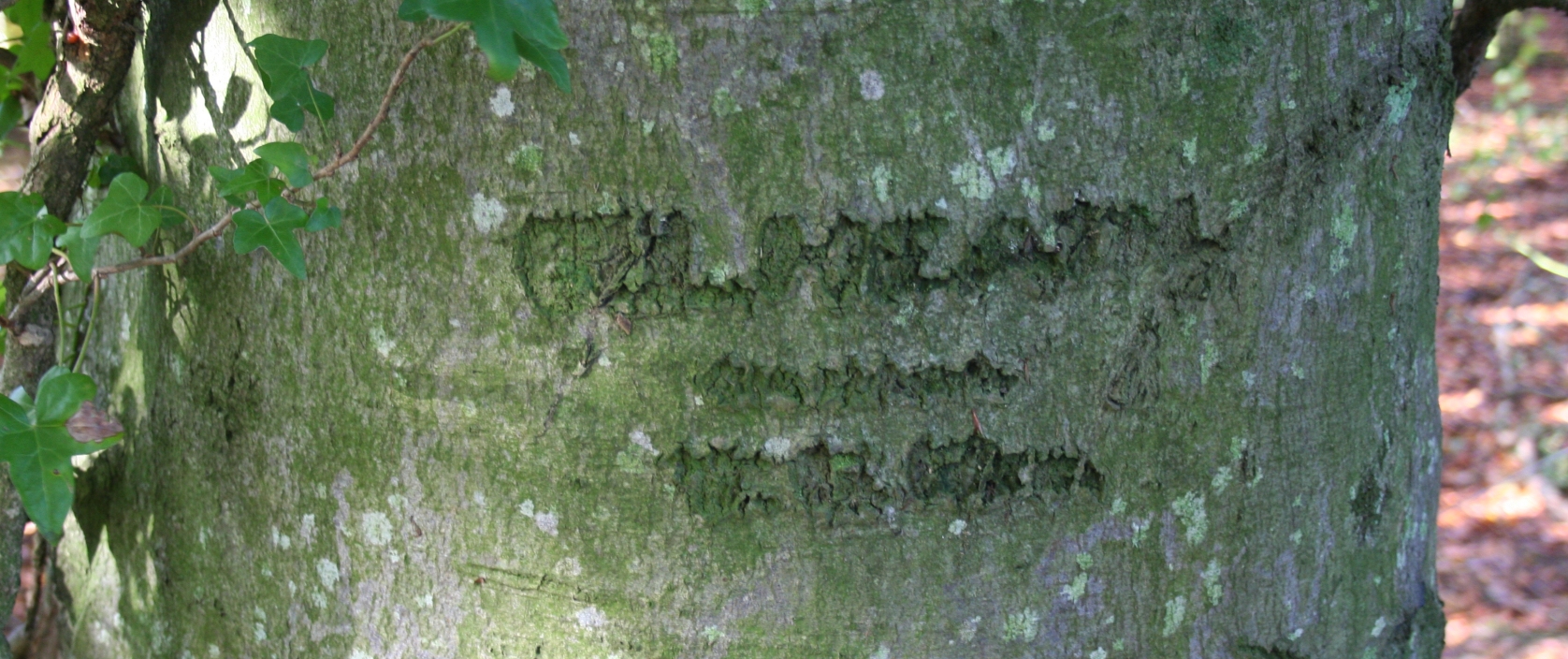

IDing Soldier #3 could be a tall order. Scratched onto the eastern side of an ivy-wreathed shade-giver close to Decker’s tree, is a name that looks to me like ‘BILL HEATH’ or ‘(Unknown initials). L. HEATH’. I suspect the heavily scabbed scar directly below once read ‘CANADA’. Of the handful of letters on the last line, all but an adjacent L and H (?) defy comprehension.

Plump and branchy due to their relatively exposed positions, and sometimes disfigured by embedded barbed wire and shotgun pellets, the beeches on the western fringe of the wood, sport almost no legible inscriptions. One of the few exceptions is a stout specimen a short distance north of Heath’s tree. Soldier #4, ‘F. HUNT’, hails from Down Under – that’s obvious from the big ‘AUST’ at the bottom of his carving. Working out what ‘F.W.’ (the two letters above the name) means and making sense of the third line (five or six characters possibly beginning with an ‘I’ and including a sequential ‘D’ and ‘I’) will take serious Sherlocking.

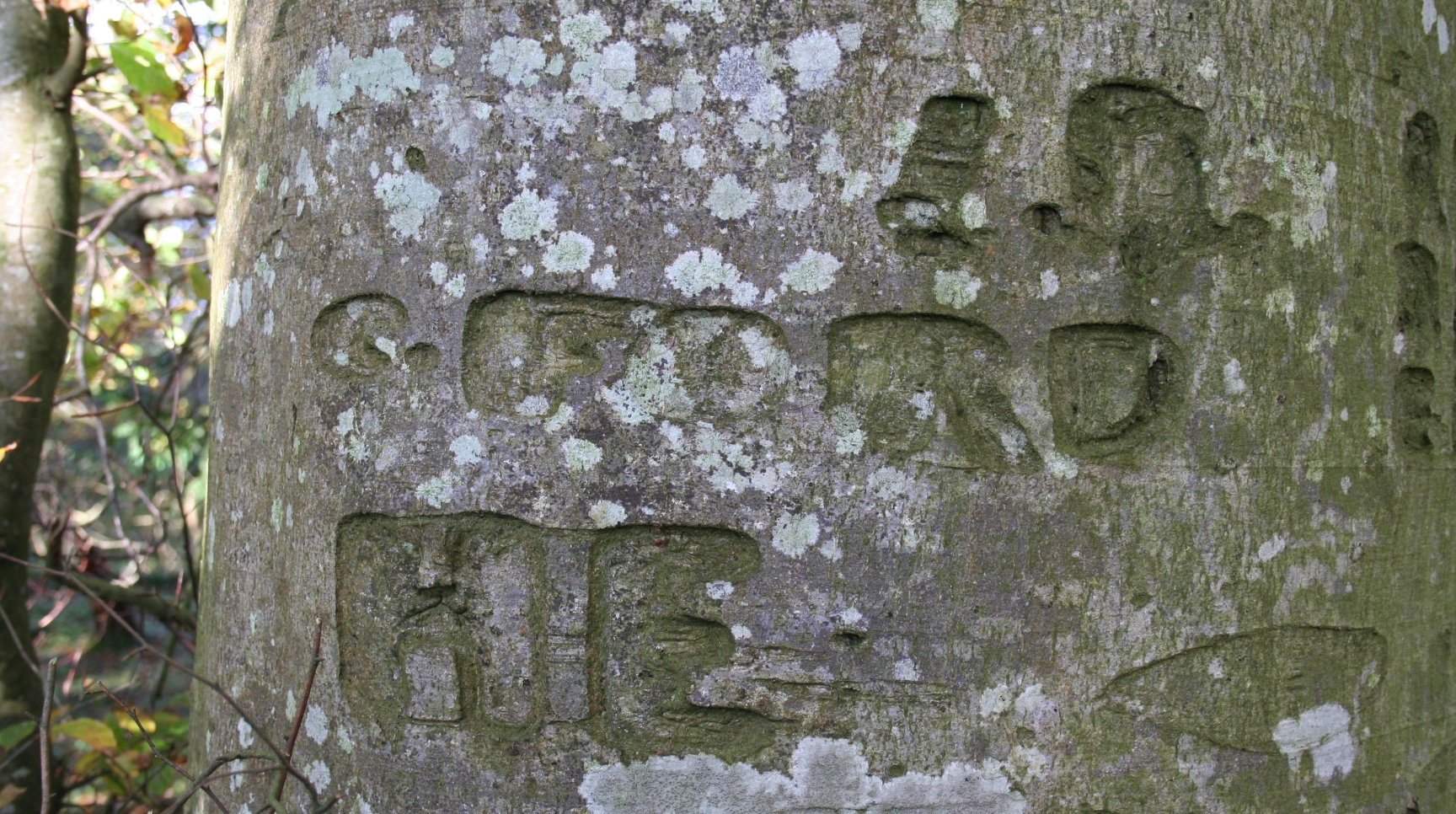

Soldier #5 (C. or G. FORD) shares his woodland pillar with several others including a chap (?) called Jean. Is that a ‘40’ above Ford’s name? What does the big ‘HE’ (or possibly ‘ME’) signify? Search me.

My heart skipped a beat when, pushing through holly bushes, I descried Soldier #6’s eighty-year-old “Hello”. As Private Gervais has a pretty unusual surname and thoughtfully provided both his Christian name – Joe – and his country of origin – Canada – his history may be more easily unearthed than some.

So there’s this week’s Friday Foxer. Six WW2 warriors calling to us from a neglected strip of Wessex woodland. Come on defoxers, let’s remember Joe and his fellow Fagus taggers by researching and telling their stories.

I don’t approve of carving one’s name into things, particularly not living wood; nor bleedin’putting padlocks on bridges.

The Canadian archives landing page seems to be here:

https://library-archives.canada.ca/eng/collection/research-help/military-heritage/second-world-war/Pages/second-world-war.aspx

HOWEVER, the easily accessible records are for those that _died_ between 1939 and 1947; quote: “The files are open without restrictions. […] All other Second World War service files are restricted under privacy legislation.”

It did turn up two Joseph Gervaises. Joseph Wilfred seemed the more interesting one, but he was known as Fred at least part of the time; this caused issues as his marriage certificate was under that name (open his records, page 35 of 46). He certainly spent some time in the UK (regimental paymaster in Bordon, Hampshire).

I think Joseph Wilfred Gervais is our man. A widowed bilingual lorry driver (he’d also worked as an elevator operator, self-employed painter/landscaper, and lumber company labourer/foreman) from Ottawa, he was born in 1904, enlisted in September 1939, and served with the Royal Canadian Ordnance Corps’ No. 1 Ordnance Store Company, mostly in Southern England, until discharged “unable to meet required mil. physical standards” in May 1945.

His entire military records are available online and tell a pretty sad story. At various times he’s hospitalised with bronchial complaints. Judging by the fact that he died of “carcinoma of lung” in August 1947 it’s possible his “chest trouble” was actually undiagnosed lung cancer.

Health-wise, he was clearly struggling at the time of his discharge:

https://tallyhocorner.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/barkface19.jpg

Can’t be Canadians, no one carved any penises….unless decorum has prevented you from sharing images of them.

Can’t add much to the discussion other than to note The Toronto Scottish were the divisional support battalion and only sent 120 men to Dieppe. One was killed and eight wounded but their role was fire support. I dimly seem to recall many of them may have been used to man anti-aircraft guns on the landing ships and so never disembarked because that wasn’t their job. Four men did get captured so they either disembarked or were on one of the ships that was lost close in to the beach.

I can tell you what the 40 may possibly mean. It may refer to the unit number painted on vehicles. The Toronto Scottish used a 64 on black square, while 40 was used on the headquarters units at divisional HQ as well as divisional artillery, divisional signals, divisional engineers, etc. More info here:

https://www.canadiansoldiers.com/vehicles/markings/unitsignsinfantryunits.htm

I would doubt this interpretation given how commonly the number was assigned, and it was usually used to identify units, for example as a quick and easy signpost for convoys to follow to a bivouac site. That would be done with lumber and paint in that situation. Would be unusual I think for an individual to do it – but one never knows.

As for the regimental numbers, they were assigned in blocks to units. Toronto Scottish had block B75500 to B77058. I’d say your sleuthing is pretty good. The numbers can sometimes lead you astray, guys got transferred all the time and kept their original numbers but a good start and in this case consistent with the other evidence.

B74139 would have been from the 48th Highlanders of Canada, also a Toronto regiment.

B53148 and B53142 were in the block of numbers assigned to District Depot 2, Royal Canadian Ordnance Corps, also located in southern Ontario.

Thanks, Michael. Interesting stuff.

The Toronto Scots seem to have had a pretty gentle introduction to WW2…

Guard duty at Buckingham Palace:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=JQgTO9XIbvg

Ice hockey matches at Wembley:

https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=2782808001828253&set=pcb.2782858758489844

Bizarre training exercises with Airdale Terriers and carrier pigeons:

https://www.facebook.com/965670253542046/posts/mascots-of-the-toronto-scottish-regiment-from-world-war-ii-onwardsfirst-this-is-/2126914167417643/?locale=zh_CN

Obviously, things got more serious/deadly later on. In addition to participating in Operation Jubilee, they were in the thick of it in Normandy and Holland. This interesting article…

https://scholars.wlu.ca/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1425&context=cmh

…makes me wonder whether there were Bren Gun Carriers parked close-by when M Decker and Co. did their carvings.

Australia is more helpful as you can search the Nominal Rolls

https://www.dva.gov.au/recognition/commemorations/records-and-military-history/nominal-rolls/list-nominal-rolls

I make it 45 “F… Hunt”s of which two are obviously female (Faye and Florence).

It needs more filtering and cross-referencing. The only one with a curious ‘DI’ was Fleming Ronald Hunt whose “Locality on Enlistment” is given as BENDIGO which doesn’t fit so far as I can see.

Cross-referencing is taking the name and entering it in the National Archives of Australia:

https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/SearchNRetrieve/Interface/SearchScreens/NameSearch.aspx

Search ‘All records’, limit it to the years 1939 to 1945, then view the ‘Digitised Item’.

I was in Totnes a few years back and visited their excellent Norman motte and bailey castle. During the war some Italian POWs were kept there and they carved their names onto some of the trees in the bailey.

I’ve just read a passage in a WW2 memoir (https://digital.scaa.sk.ca/sli/SLI_MajorMitchellsBook.pdf) that may shed light on what the Tor Scots were doing in a beech wood close to Salisbury Plain in 1940.

(The first line raises the possibility that I’ve misread the month digit in ‘M. Decker’s’ inscription)

“During April we, and the Toronto Scottish, spent a month doing field firing and training on Salisbury Plains. Our camp was at Bulford. We lived in tents. A great portion of the time rain fell and it was most disagreeable. We lived under British army conditions. Some things seemed so senseless. I can still see the chief instructor’s hands, one cold wet day. He had us out in the open doing some training. During all the time his hands were bare and a blue black in colour, from the cold. For some reason he did not wear gloves and it seemed so stupid to me.

Nearby was the town of Amesbury. One Sunday, Vergne and I walked over there and stopped in at a tea house for refreshment. I casually asked for ice cream. I can still hear the waitress’s retort.“Where do you think you are – in London?”

Near Amesbury the RAF had an experimental air station. They had some ninety different kinds of aeroplanes. The Halifax and Lancaster bombers were a revelation to me. It was incredible that such huge things could be lifted off the ground.

I was on B Company’s strength. I had not done any training with the Company at Farnborough so I more or less tagged along with my platoon. As always happens, the platoon sergeant carried the load. The chief instructor, one day, quizzed me quite closely. I had spent my spare winter moments with the pamphlet. I guess I had memorized some parts. At any rate this instructor, who had written the pamphlet, was overwhelmed by getting the text back, verbatim.

The two Battalions trained separately under the same staff of the Netheravon Small Arms School. The climax of the period was to be a shooting competition between the two Battalions. During the training, the Company, the platoon and the section, with the best firing record was chosen to represent each Battalion.

That was one of the most memorable days in the history of our Battalion. Many explanations are given depending on whether the speaker is Toronto Scottish or Saskatchewan. LI.

The competition was held on a six hundred yard range. On a sand embankment, six hundred yards away, were a dozen or so steel plates which would bounce when hit with the bullets. It was a clear dry day and there was a gala spirit in the air. Both Battalions had trained very hard. Each were determined to demonstrate their merits.

Major McKerron was a machine gun officer in the First War. The evening before the shoot, he very quietly took the Armourer Sgt. and the twelve machine guns to be used, off to a range where they zeroed the sights. No one in the Toronto Scottish Camp thought to do so. That is a point that is rarely mentioned. The Toronto Scottish thought that zeroing the guns was not quite cricket. The instructional staff on the school were very happy to find that our Battalion was so competent. We were training for war. At any rate the actual competition was begun on terms that were not quite even.

For the competition the guns and stores were laid out on the ground, dismantled. The gun crew, on the command to begin, ran thirty yards, picked up stores, ran another thirty yards, and went into action. The first to hit the plates won. I have never attended a sporting event anywhere when the competitive spirit and excitement was higher.

It was a very thrilling occasion. Company, platoon, section, Officers, Sgts, and Cpls. The Saskatchewan. LI won every event. It was a complete route (sic). After that period of training the Saskatchewan. LI. was chosen as the Machine Group Battalion for the 1st Division. The Toronto Scottish were slated for the 2nd Division. It was a wonderful finish to a hard cruel winter.”