Few parts of the UK have had such a profound impact on the world as the mineral-rich corner of North-East England I’ve picked as the venue for this Tally-Ho Corner rail tour. A pioneering rail network conceived and constructed two centuries ago in County Durham demonstrated the viability of long-distance, loco-reliant, public railways, and in doing so ushered in the Industrial Revolution’s second phase.

D5167, the Class 25 diesel that will be hauling us the 23 miles to Durham, was manufactured right here in Darlington in the early 1960s. It’s wearing its original green and yellow livery for the same reason your driver (Roman) and your guide/waiter (Yours truly) are dressed like extras in a British New Wave movie. The Train Simulator Classic 2024 add-on powering this virtual peregrination recreates the grimy pre-Beeching vistas and track layouts of the 1950s and 60s and we didn’t want to spoil the aesthetic.

A typically grand Victorian edifice, our starting station is relatively young compared to some of the railway infrastructure we’ll be passing later. Not part of the original Stockton & Darlington network (George Stephenson’s line passed just north of the town, trains stopping at a makeshift halt called North Road) this building’s modest predecessor overtook North Road in significance and prestige when it found itself on the line linking York and Newcastle in the mid 1840s.

Considering Darlington’s proximity to the Great Northern Coalfield and the North Pennines orefields, and its role in the birth of modern railways, it’s hardly surprising the lineside scenery on the first stage of our journey northward is dominated by heavy industry.

For 150 years the town’s main employers were ironworks and railway-related plants. That’s the sprawling premises of the Darlington Forge Company on the right. They specialised in making giant castings for oceans liners. The colossal stern frames, brackets and rudders of vessels such as the Titanic, Olympic, Mauretania and Lusitania were manufactured there.

While few Brits my age would be able to name the historic structure that’s bearing our weight at present, all will have held a likeness of it in their hand at some point. Depicted on Series E five pound notes in circulation between 1990 and 2003, Skerne Bridge is the world’s oldest rail bridge still in use. It was first vibrated by a train on September 27, 1825, the day the S&DR opened.

Bound for Stockton at the western end of the line, the train in question – an inauguration special hauled by Locomotion – had just restarted after pausing here at North Road to disembark and board passengers, take on coal and water, and attach some literal bandwagons. On that momentous day there was nothing here, or indeed anywhere in the world, that could be described as a railway station.

The days when new steam locos emerged weekly from North Road Locomotive Works – that extensive factory complex on the right – are, of course, long gone, but thanks to the A1 Steam Locomotive Trust the tradition of building descendants of Locomotion in this part of the world, hasn’t entirely died out. Based in a new workshop sited just over there, the charity that unveiled Tornado in 2008, is presently constructing an improved LNER P2 from scratch.

One of the disadvantages of doing this trip in the early Sixties is that, close to Heighington, the next station on the line, we don’t get to gawp at Hitachi Rail’s Newton Aycliffe plant. In recent years many of Britain’s fastest trains (Classes 800 to 810) have been assembled here besides the S&DR. Whether you consider this a pleasing bit of historical circularity or a saddening sign of Britain’s industrial decline depends on your perspective.

It was at unprepossessing Heighington that Locomotion took to the rails for the first time and, a few years later, slew a reckless (he’d tied down the safety valve) driver by bursting her boiler. The unfortunate John Cree wasn’t the first train driver to lose his life in a boiler explosion. In 1815 at Philadelphia, County Durham, the bizarre Mechanical Traveller, a loco propelled by mechanical legs, blew up killing at least a dozen people including its operator.

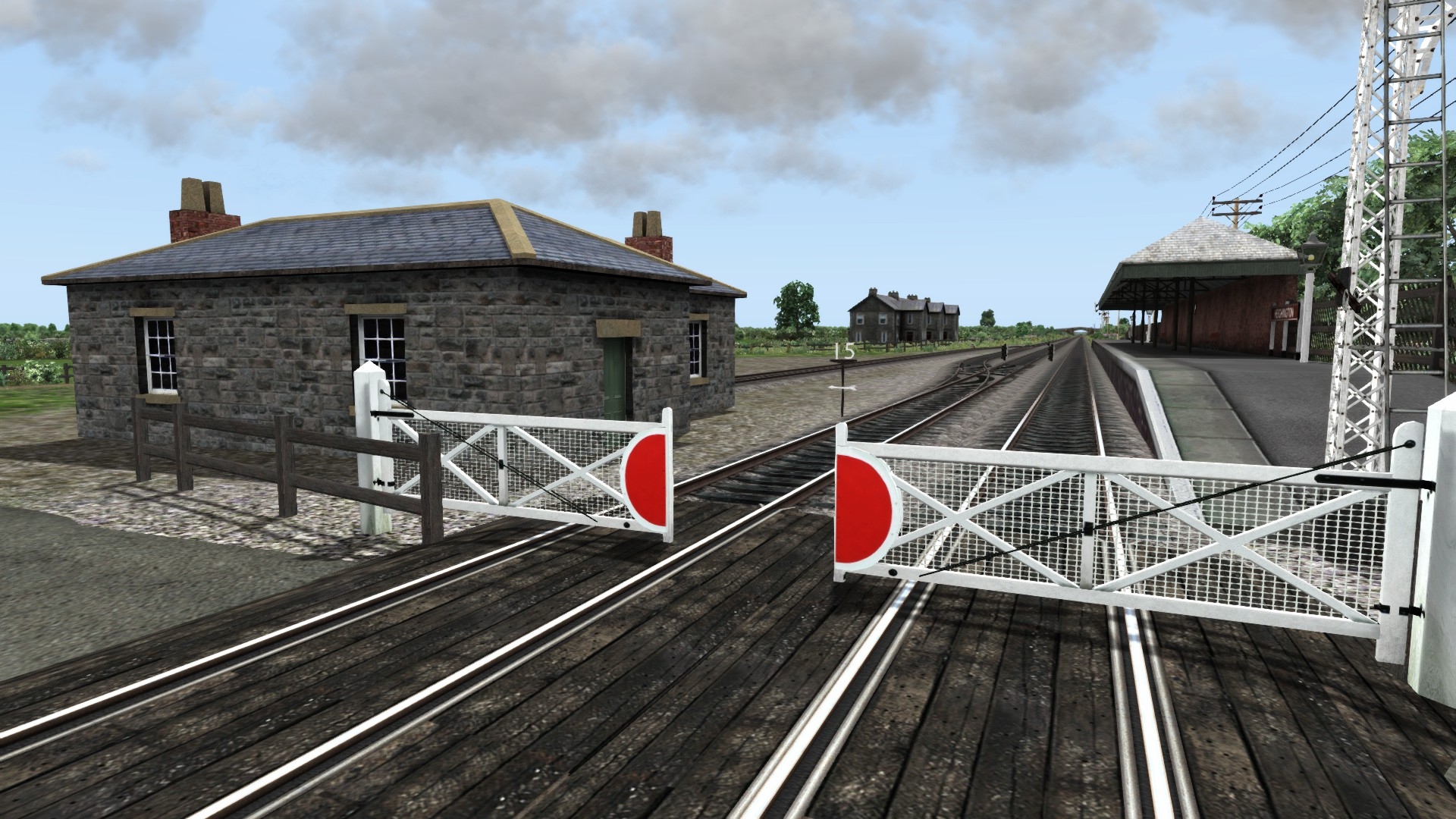

It was also at Heighington that the S&DR built what most historians consider to be the world’s first railway station. Inspired by the coaching inns that dotted the British road network at the time, the company began constructing ‘railway taverns’ close to their stopping places in 1826. The one at Heighington was adjacent to the line, featured a platform, and soon began fulfilling the functions we now associate with railway stations. If the Friends of the Stockton & Darlington Railway get their way this important survivor – which lacks its adjoining cottages in TSC2024 – won’t be semi-derelict for much longer.

Beyond Heighington, the line runs alongside the western perimeter of a vast industrial complex constructed during WW2. Mainly staffed by women, Royal Ordnance Factory Aycliffe produced around 700 million rounds of .303 ammunition during the war, along with other munitions. Although the Germans were aware of it (Lord Haw-Haw mentioned it in one of his propaganda broadcasts) the Luftwaffe doesn’t appear to have caused any damage to its berm-protected buildings or 17000-strong workforce. Workers perished in accidents, but I couldn’t find any reports of successful bombing raids.

This sheaf of sidings south-east of New Shildon together with the massive wagon works to the west might no longer exist, but there’s still good reason for a rail enthusiast to visit the world’s very first railway town. Named after one of its most notable/local exhibits, the UK’s second largest rail museum, Locomotion, is sited here and boasts a splendid collection of historic rolling stock including the Deltic, HST, and APT prototypes, and authentic S&DR coaches.

Glancing at the 178-year-old S&DR coal drops on the approach to New Shildon station, I find myself reflecting, not for the first time, on the lack of options available to simmers interested in early railways. In recent years, things have got much better for railway modellers into ‘Era 1’, but for PC owners keen to operate groundbreaking machines like Locomotion and Rocket on period lines, the situation remains frustrating.

Branching right at New Shildon bound for Bishop Auckland, we leave the course of the original 1825 S&DR and take to a line added to the network seventeen years later. While early in its history the pragmatic S&DR dealt with the steep inclines at the coal-rich* western end of its empire with stationary winding engines, three of its company directors had sufficient cash and vision to privately fund the 1120 metre-long Shildon Tunnel in 1842. The branch neutralised a formidable limestone ridge, allowing the railway to spread its tendrils northwards towards the collieries between Shildon and Durham – territory we’ll be traversing on the second leg of the tour.

* The primary reason for building the S&DR was to allow coal to be moved cheaply and quickly from the collieries west of Shildon to County Durham’s major port and industrial centre, Stockton.

(To Be Continued)

A great start for this train trip! As before, a great way to learn about a country and it’s history. Well done and thank you Tim!

And I can’t imagine a loco propelled by mechanical legs… What a wonderfully crazy idea! 🙂

When I was reading the article I was imagining some kind of mechazilla automaton walking across the Earth. For some reason your suggestion of a “loco propelled by mechanical legs” made me think of these giant articulated limbs being used to pedal a drive-chain instead!

Ah ha! the real “Mechanical Traveller” image was a bit disappointing I guess, as I, like you imagined a walking mechazilla!

Love this! I spend a lot of time watching UK cab ride videos on YouTube. For those interested, two of the best channels are run by Don Coffey and Ben Elias. Don’s videos in particular do a wonderful job of highlighting the changes that have taken place of the years and calling out sites of historical interest.

I love this sort of THC whimsy the most.

Thanks for this, both fun and interesting.

Thanks, I enjoyed the journey commentary.

Michael Portillo’s 200-years of the Stockton-Darlington railway is on BBC2 on Tuesday. If we’d paid more attention we might’ve been able to moon the pastel {insert word of your choice}.